Travelogue: A reunion in Aburi

By Wale Okediran

THE sun was still up when, out of the distant hills, Aburi came into view. At first tiny like the head of an infant, the historic Ghanaian town soon came into full sight after we exited the highway and climbed the steep incline pressing ourselves against crash barriers as other vehicles including heavy trucks rumbled past, inches away.

We had set out at noon, in the heat of an Accra September day. Three of us. I sat in front with Ivor while Professor Wole Soyinka, the Nobel laureate in Literature sat behind, his white mane glistening in the sunrays that peeked inside the SUV.

With the same dexterity with which he weaves his narratives in many of his cerebral works the writer, critic and academic Ivor Agyeman-Dior, expertly maneuvered the light blue vehicle from Kempinski Hotel on Gamel Abdul Nasser Avenue to join Independence Avenue on to Liberation Road and then on to Aburi.

As the vehicle continued its ascent, we could see far below Accra with its scenic rooftops amidst a spotting of jagged hilltops. On our left, far above the golden orange horizon of the late afternoon sun were the line of hills as they rolled into each other, indistinct and pale before merging into a beautiful and delightful totem.

At the peak of our climb on the left emerged the Aburi Presidential Lodge, safely ensconced behind heavy security gates. And, as we passed the historic site, my mind went back to January 1967, as I imagined a flurry of activities taking place behind the heavy gates as the major Nigerian military leaders sat down to sign the famous but still-born ‘Aburi’ accord.

Aburi, a town in the Eastern Region of South Ghana is said to be famous for the Aburi Botanical Gardens and the Odwira festival. However, what many war historians including Nigerians will remember the town for was the memorable, if not emotional role it played in the history of Nigeria, particularly in the countdown to the infamous Nigerian Civil War that plagued the country between July 6, 1967 and January 15, 1970. The Aburi meeting which took place between January 4 – 5, 1967 was between the then Nigerian Head of State, Lt. Col. Yakubu Gowon and the other Nigerian governors including Lt. Col. Odumegwu Ojukwu. The meeting was chaired by the then Chairman of Ghana National Liberation Council, Lt. General J A Ankrah.

History has it that the Aburi Accord or Aburi Declaration was reached at a meeting between January 4 – 5, 1967 in Aburi, Ghana, attended by delegates of both the Federal Government of Nigeria (the Supreme Military Council) and the Eastern delegates led by the Eastern Region’s leader Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu. The meeting was billed as the last chance of preventing and all-out war. Unfortunately, the accord did not prevent the two and half years’ Nigerian Civil War which claimed an estimated two million people.

The Aburi trip was Soyinka’s idea. In Ghana for the 2023 Labone Literary Festival expertly curated by my good friend, the witty and debonair Chike Frankie Edozien, Professor and Director, New York University, Accra, Soyinka wanted to pay a condolence visit to his old friend, H. E. John Agyekum Kufour, the former Ghanaian president who had just lost his wife of 60 years, Theresa Aba Kufuor in his Aburi home. In his usual manner whenever visiting Ghana, Soyinka had sent me an email about his visit as well as a request to meet him in his hotel.

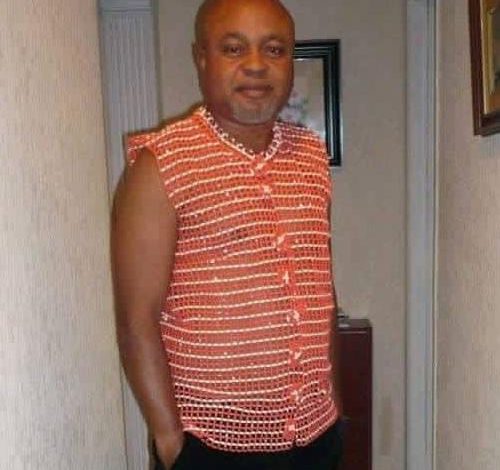

Former Ghanaian president John Kufour (left); Ivor Agyeman-Dior; Dr. Wale Okediran and Prof. Wole Soyinka at the Kufours’ home in Aburi

It was always a delight to hang out with the avuncular writer and benevolent senior citizen.

Apart from the chance of learning once again from his wealth of experience on several subject matters, visiting him was also a good opportunity for me to give him updates about the activities of his beloved Pan African Writers Association (PAWA) of which he is a foundation member while I’m the current Secretary General. Expectedly, in order to enjoy such occasions, it is always important to be up-to-date with facts and figures since the Nobel laureate would be ready with questions and inquisitions which you must adequately answer.

In addition, if you are a writer you must be ready for some grammatical and literary critique sessions which the master usually reserved to the end of the meeting after he must have given you a good meal and some wine. In order to be at your best performance with a clear head, I discovered that it’s always a good idea to be careful with the wine and not compete with him if he was your host, a well-known connoisseur of good wine.

Unlike Wole Soyinka’s forest enclave in his native Abeokuta in Nigeria where you are welcomed with a grim and scary signpost ‘TRESSPASSING VEHICLES WILL BE SHOT AND EATEN’, no visible signpost welcomed us to what Soyinka himself referred to as the former President Kufour’s ‘baronial’ house.

Despite the short notice for the visit, our three-man delegation was effusively welcomed to the magnificent and sprawling property where Soyinka wrote a substantial portion of his latest book, his first novel in 48 years, Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth.

As WS put it in a newspaper interview, “While writing the book, I discovered that I needed some detachment from Nigeria. On my first stint in Senegal, I set down a chunk of the novel. Then I had to go back to earning a living. Believe it or not, I still have to do that, going out lecturing and so on. And then I started looking for another short stretch. President Kufuor, a friend, offered what I call his baronial house in Ghana. So I moved from that little cottage by the seaside to the lap of luxury. I was looked after hand and foot and I was very appreciative of both.”

In his review of Soyinka’s book, Ben Okri had this to say, !In summary, at the heart of Chronicles… is the tale of a quartet of friends who form themselves into a fraternity called the Gong of Four and how they maintain their integrity and are drawn into the maelstrom of political life that surrounds them. In a microcosmic sense it is a portrait of how a generation betrays and is betrayed by the prevailing ethos of moral entropy.”

Regarding the observations of some critics about Soyinka’s style in the book, Okri further observes thus, “One thing to be clear about from the outset is that with certain writers of highly individualized voices, highly cultivated ways of seeing, there is nothing you can do about their styles. It is an inescapable fruit of how they see the world. Like Henry James, like Conrad, like Nabokov, there is no choice but to get used to the style, to saturate yourself in it. But once you nestle into that tone, something wonderful happens and a rollercoaster ride of enormous vitality is the result.”

In going to Aburi, it was obvious that Soyinka wanted to use the occasion of his condolence visit to cheer up his old friend as he regaled those present at the Kufours home during his visit with beautiful memories of his long term friendship with his friend and late wife of 60 years. He even informed the gathering that he was the first occupant of the palatial house long before the real owners moved in.

Regarding the nearby Presidential Lodge where the famous ‘Aburi Accord’ was signed, Soyinka who was imprisoned for 22 months during the Nigerian Civil War in the late 1960s for daring to visit the then rebel leader Ojukwu in an attempt to broker peace, said he refused to visit the lodge in order to blot out the annoying memory of the civil war.

After a very cordial moment during which the two friends exchanged banters with each other and some of the visiting dignitaries, we moved to the dining room where the reunion between the two friends became more heighted as they continued their warm reminiscences over lunch and the ensuing photograph sessions. Even though Soyinka had originally planned for a very brief visit, as he put it, “just to sign the condolence register”, it was late in the evening before we took our leave.

As Ivor steered the vehicle out of the historic town of botanical gardens and a cultural festival, sightseers and tourists could be seen relaxing in the shades of the claustrophobic streets in their reunion with nature.

It was obvious that in Aburi, visitors find joy in small ways – birdwatching, enjoying the flower garden and taking life slow by soaking in the rarefied weather of the highlands. To the west, the sun could still be seen perched on a wall of clouds while to our left, beyond the deep gully of the road, the distant roofs of Accra beckoned.

About 90 minutes later, we reached our destination. As he alighted from the vehicle, Soyinka quickly briefed Ivor and I about his forthcoming travels and projects.

It is amazing that at almost 90 years of age, Soyinka still has a relentless drive for work and achievements. Coupled with this is a joie de vivre and an irresistible sense of humor that usually comes to the fore when the elderly savant regales his audience with some of his travel stories and hunting escapades. I have often thought of making a compilation of these witty anecdotes perhaps for the benefit of some of his readers who still find Soyinka’s works difficult and inaccessible.

As we later said goodbyes outside his hotel, Soyinka asked for my opinion on a personal medical issue. “I think you now have to start drinking some water, sir,” I said in response. He gave me a mournful look, shook his head and walked in his typical ram-rod straight posture into the approaching Accra twilight.

Okediran, a novelist and travel writer, is the Secretary General of Pan African Writers Association (PAWA)