What it comes to prizes, you take what you’re given, says Uwem Akpan

By Anote Ajeluorou

THE debate over who wins a (literary) prize will continue to rage as long as writers and cultural workers exist to observe and writers continue to write. Classical examples are two of Africa’s venerated writers – Chinua Achebe and Ngugi wa Thiong’o – who many continue to lament were denied the Nobel Prize largely on account of their non-conformist creative vision to the European establishment which they excoriated in their writing and public outings. These eminent ancestors refused to fit into essential Euro-centric cultural subservience, and in fact actively railed against it to the point of demolishing it as counter-productive to the African psyche and way of being. It was something the European cultural establishment couldn’t stomach, and so each year these two cultural giants were passed over repeatedly until they joined their ancestors. But those for whom their writing and cultural activism and vision benefited had already award them a million Nobel Prizes and more in their hearts, as worthy ancestors who fought a good fight to rescue Africa’s cultural consciousness from European shackles.

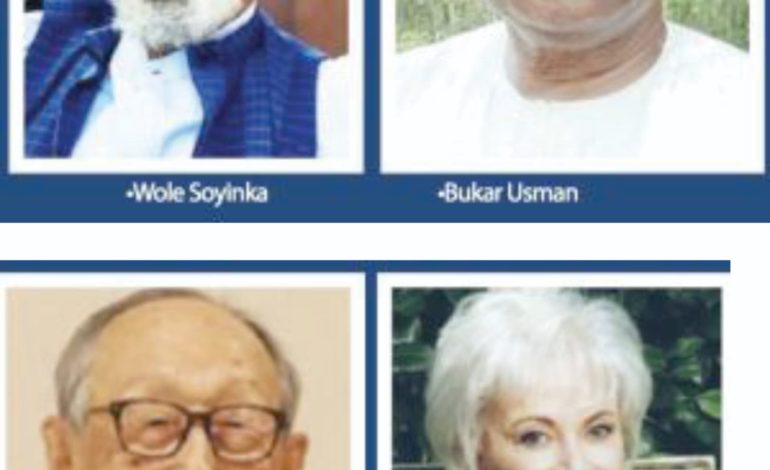

Author of New York My Village and America-based writer and creative writing teacher, Uwem Akpan, has suggested that prizes are as good as those put together to administer them, and that as a creative, you take what you get and no more. He offered this piece of advice to youngsters in Ibadan when he read in the ancient city last year. He added that prizes, just like writing, were also political, noting that it appeared that the Nobel Prize in Literature was being rotated on a regional basis in Africa, with East Africa’s Abdulrazak Gurnah of Tanzania taking the recent slot since Wole Soyinka took West Africa’s slot in 1986. North (Naguib Mahfouz – 1988) and Southern Africa (Nadine Gordimer – 1991 and J. M. Coetzee – 2003) had also taken their turns.

“What it comes to prizes, you take what you’re given,” Akpan advised writers. “A prize is as good as the people (judges) they put together (to administer it). Today, they can put together a panel of judges, and they may be interested in feminism, for example. They’re going to pick a book that goes with that. Then maybe this panel is interested in queer theme and that’s the book they will give. So when you write a book, you send it in with a prayer. Have you ever sat with your friends and say, who are we going to give a gift this coming Christmas? Or even you and your wife? The conversation is never easy. Or you alone want to decide: one side of you will say Ajayi, the other side will say Kunle. So, when it comes to panels of judges, it’s what it is. There’s politics.

“Now that they have given it to Gurnah, don’t expect it to go to that part of the world soon. So, they gave it to Wole Soyinka around this area in West Africa. You see how long it has taken? They try to make it go round. So yes, it’s very political. And the politics actually begins with their agents. When you finish writing a book, you try to give it to an agent to sell to a publisher. The agent reads the book and says he’s not interested. That’s already prejudgment. That’s not going to make the canon, because it’s been preselected negatively.

Uwem Akpan

“Many big, big writers who never got the Nobel prize – Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Philip Roth, John Updike. Someone like Achebe, I like to see him as someone who was even beyond the Nobel prize, because he got the readership he wanted. Things Fall Apart told white people we have a different culture. Nobody ever convinced them we had a different culture, that we have our ways. They didn’t give him the Nobel prize; it was unfortunate.”

Akpan’s New York My Village is intensely critical of western publishing establishment and its equally intense politics of selection that keeps out outsiders. Although he hadn’t worked in publishing before, he said he had friends who guided him through the period of writing, friends who corrected his register to fit into the American mode of viewing multiculturalism and racial differences in American publishing environment.

“On my hard stance on American publishing – it’s because I have friends in the system who agreed with me that 93% of those who work in publishing are white,” he said. “And it’s not just the editors. What about the agents and publicists? All white. So how are you going to get in? The whole system is white. So it needed to be said, and I said it. Some day I will tell how rough it has been since I said it. Of course, the protagonist Ekong ran to New York and ran into racism. I have never worked in publishing as Ekong did. I do my research and try to work across barriers, so I can do my work.

“And I have friends in publishing who corrected my language register to say, ‘we don’t say a black book, we say a multicultural book’. You see the difference? Because there are blacks and Latinos in America who must also be included in their narrative. I’ve related with people from different backgrounds in my writing and as a human being. I used to be a Catholic priest.”

Just as New York My Village is critical of white dominance in publishing and often excludes outsiders, so also is the book critical of the way Biafra brutally prosecuted the war in minority areas that is home to the protagonist Ekong. But Akpan acknowledged that it was his Igbo friends who helped him contextualise the narrative and guided him along the way.

“In fact, as painful as my book is to the Igbo, it was actually my Igbo friends who helped me do the research,” he offered. “They said to me, ‘Uwem, you have been our friend, and we did not know what happened to your people in Biafra. We will get you the information you need, because this story has to be told.’ Can you imagine that generosity? So when I write like this, it’s not because I don’t have Igbo friends or appreciate (them). On the contrary, many of my friends are Igbo. People and writers like Chika Unigwe, Okey Ndibe; as soon as this book came out they went online and urged Igbo (people) to be open to what Uwem is saying, because this is a new dimension to this (Biafra) story.”