What Europeans did was to break Africa’s storyline, make it difficult for us to look back with comfort, says Obe

By Anote Ajeluorou

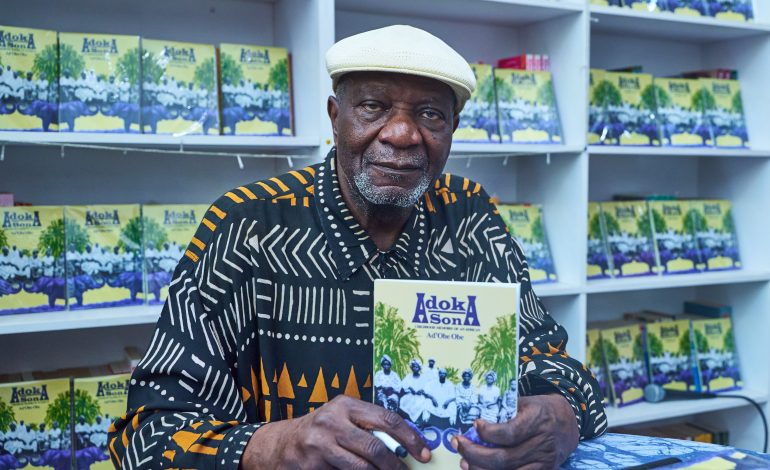

When 77 years’ old Mr. Ad’Obe Obe held a book reading and signing event at Ouida Books office, Ikeja, Lagos to unveil his memoir Adoka Son: Childhood Memoirs of an African, it was a gathering of friends and family who had been part of his life since youth. Veteran journalist Mr. Dan Agbese, with whom he attended the same primary school, now converted to a secondary to erase all memory of that pioneer institution, retired Col. Kayode Are, former Cross Rivers State governor, Mr. Donald Duke, Executive Director of TheNews, Mr. Kunle Ajibade, Lady Ejiro Umukoro of Lightray Media, Dr. Olaokun Soyinka, Ake Festival director, Lola Shoneyin, Olatoun Gab-Williams of Borders Literature, and many others witnessed the event. Apart from audience members asking questions, Anote Ajeluorou and Nancy Sabo also engaged Mr. Obe on significant cultural issues regarding his book. Book lover and Group Art Director at PremiumTimes, Mr. Ebun Aleshinloye coordinated a seamless event. Before signing copies, Mr. Obe took moments to reflect on what happened to the black man in his unequal encounter with the white man. Raised at a moment of great transformation in his native Idoma land with the arrival of the white man and his culture that ousted old Africa, and having lived among them, Obe knows firsthand the psychological and mental damage the white man wreaked on the African mind by cutting him off from his rich past, so he couldn’t challenge him in his quest for domination. He also spoke about the role Christianity played in the white man’s planned evisceration of the black man to make him less human, shun his past and therefore amenable for subjugation

What motivated you to write Adoka Son? An d how did you source for materials?

THE story emanated from conversations that I had with my mother, after my father died. My mother was 90 and I was 70, and practically everything that is here in the book is known to everybody. The European’s encounter with my Uncle Ella, who was a nudist in our midst. The point I’m trying to make is that even though it’s in the culture, the only person who found it odd was the white anthropologist McConnel (Umakone) who came. When I got to write this story, most of the stories that were being told… had a different perspective because I had gone to England, and I had also attempted to join a nudist club in England. Then, I saw the encounter between the white anthropologist and Ella, who was a self-declared nudist and respected for it, and then the story about how the anthropologist went to England and published the picture that he had with Ella in a UK nudist magazine, and brought it home and showed it to Ella, and he was very excited.

Then he said, “these people’s private parts are covered. Why is mine not covered?” The white man said that’s how it is. “Why did you show my nakedness to people I don’t know,” and he just tore up the magazine. This is a standard story among our people, but when I combined it with my experience of nudism, the whole dimension because so real. Here is Ella who was naturally nudist, and here is an English person who is praying only if he be like him, and they were not speaking the same language, but at the same time, they were getting on well together. And practically everything, like the coronation of Queen Elizabeth is a story, but nobody could quite comprehend it because leaving Idoma land to go as far as England was beyond anyone’s imagination. Then, the reception that the king had in my father’s compound, to celebrate the success of his trip to England took a different dimension, because I have been in England and I saw how these people plan things. I put these together knowing this is how the English people arrange things. We had a special dinner that was arranged by the first D. O. of Idoma land. What can he say to people if he doesn’t know them?

So all of this came together, and that is why my favourite chapter in this story is the situation where I literally died for several hours because of the Chinese flu of 1957, and then I resurrected. So, instead of just landing the story there, I said, “let me create a dream that I had when I was dead, and that makes this particular session historical because it’s fictional, but it’s also based on facts. I’m going to read to you the dream I had when I was dead.

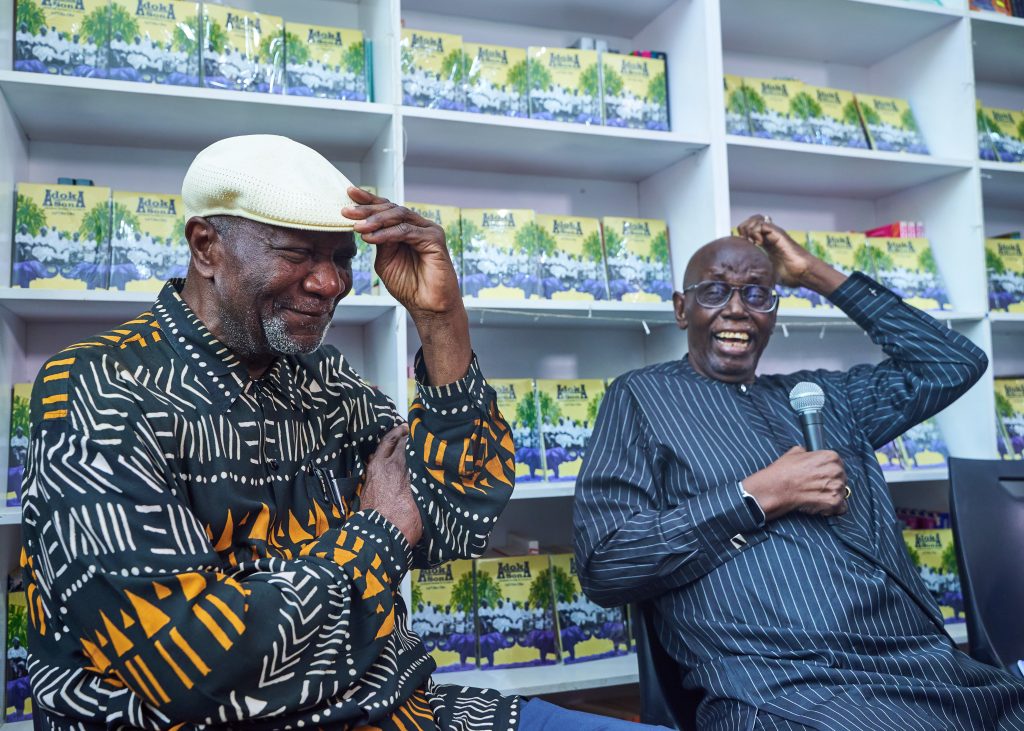

Author of Adoka Son, Mr. Ad’Obe Obe and veteran journalist and co-founder of News Watch, Mr. Dan Agbese having a good laugh reminiscing old times at the book signing event in Lagos

There’s so much explicit use of language in the book. Was this deliberate?

This is a completely English thing… and there are so many proverbs where we, Idoma, Africans mention human sex organs. Like mentioning my mother’s breasts; there is a saying that is equivalent to ignorance is bliss. You don’t know anything about sex organs and that’s it, though you know your mother has it, you have no thoughts of it, and you don’t deny that it exists. In that respect, our culture is so open-minded and we say things as they are. The English language, by contrast, is shy about mentioning sex organs…

Having lived among white people and knowing what you know about Africa’s relationship with them, are you any the wiser about what happened to Africans in he hands of the white man?

It is my going to Europe that changed my perspective, because I got to know the white man up close. People like (Chinua) Achebe didn’t know white men. I got to see the character of white people and the design of colonialism whereby people actually planned for the missionaries to help manage African thinking. When the God-fearing Christians among them said, ‘you cannot do this to a fellow human being,’ they got others among them to degrade us by calling us pagans. If we were pagans, we were not humans, and they can do what they liked to us. They had to degrade us. So, then the Christians had the responsibility to elevate us to acceptable humanity level. Then you’ll have experiences like I had, meeting someone whose grandparents actually had a slave farm. Do you know that until recently, when you heard about Mohammed Ali changing his name from Cassius Clay, up to that generation, hardly any African-Americans knew their grandfathers. They only knew their mothers. What they did was to put women in a place like cattle, then they would bring strong men to mate with them. When the children were born, they were all slaves. Many generations, up to my generation of African-Americans, hardly had knowledge of their father. This is in addition to the fact that it was deliberately designed that while they were moving Africans across during slavery, what they did was to separate them, such that no two people who spoke the same language were together. Do you know the effects on your mentality? Putting adults together, and all you can do is grunt at one another, and all of this was by design.

Then you meet people who can refer to their grandparents as being involved in all this, and then the story becomes different from the way someone like Chinua Achebe saw it. I have lived that long and been in all kinds of places there; I can never be comfortable with the white man. There are people who have made a career out of moaning about what the white man did to us, and I said there is nothing to moan about. We’ve done it, and what you should do now is to take the challenge to correct whatever you can that is within your capacity. There are professional black men who make a career out of moaning about the African condition. Every human being has a storyline, and that storyline has an origin, such that as you get older, you’ll be able to relate it when you’re dying so that it is complete. What the colonisers did was to break our storyline, and made it difficult for us to look back with comfort, because many of the things that happened to us were nasty by design.

At the end of the story, there’s an epilogue I wrote, where I used my father to tell a story and imagined that my father had gone to Europe. All the spiritual leaders had the premonition that the incoming European was a harbinger of an ill wind that will blow away all things African. My father, which is the character in this story, and his peers, can clearly observe all the social relevance of the spiritual leaders being deleted in the name of a new God in the gab of Christianity. African spiritual institutions are being categorized by their anthropologists and ethnologists as heathen, indulgences of primitive humankind, revelling in mumbo-jumbo juju, etc., through the scientific nomenclature that they have imposed on us. However, in the mindset of my father’s generation, there persists a legacy of the spiritual leaders as those who foresaw Africa being invaded by strangers who were viruses of an alien cultural pathogen against which Africa’s cultural immune system had no defense whatsoever. The manifestation of this villainous pathogen is that it chews up Africa’s past, compels Africans to live a life that begins today and infects them with perpetual angst about their tomorrow. We cannot connect our lives properly, and that’s the dilemma.

Again, the recognition of your story line. Each one of us has a storyline. We are projected on a trajectory, and the day you realize that trajectory is the day you feel ‘this is me!’ It takes time, and there are many things that may not be pleasant about it, but we all have a personal trajectory in life, and the worse you can do to anybody is to disturb it (that storyline), so they can’t remember.

I’m not trying to get anybody to think like that, but if you do, you realize the spiritual agony these people have infected us with. We tried to practice democracy but theirs is different from us, their language is different from ours. Being at the cusp of this transformation exacerbates my father. Inspite of himself, he witnesses how and why there is not much he can do about the unfolding reality, whereby he cannot be the role model for his children, the way his father had been for him. He can only wish his children would live out the essence of this existential tragedy with less pain than himself. Hopefully, they would have more to laugh about than he did, or maybe less to cry about. The rest is history.

What can you tell us about your first encounter with a white person?

I was in a Roman Catholic school, and catechism was one of the main subjects they taught in school and you learn it by heart. So, in the examinations, they ask questions on how well you’ve memorized it. So, I was first in reciting my catechism, and I went to collect my prize which was given to me by the white bishop. I put out my two hands to collect the prize. And as I was collecting the prize, my pair of shorts dropped. As I was pulling it up, a teacher asked me to use my two hands. As I collected my prize, my pants fell to the ground. So, I collected my prize and walked away. It was much later, at the age of 70 that I realized that this was my first physical contact with a white human being, and what a drama that was. I can never forget that because when the catechist and teachers went to complain to my father, my father was just laughing. ‘What do you expect him to do?’ he asked them.

When you look back at your grandmother, who was a formidable woman, and feminism as practised in Europe today, what comes to your mind?

The respect I had for my mother and grandmother is based on the neutrality of inter-sexual relationship. Women respect men, and men respect women. One day, when I came back from Europe and I was discussing with my mother, there was this issue about one of my sisters complaining that her husband was having an affair, and then the discussion went on to polygamy or no polygamy, and my mother said, ‘it’s all a question of make-believe.’ She was the first wife to my father, and when I was born, I had to breastfeed for a minimum of three years, and within the community where you have children who are malnourished, it’s because their mothers got pregnant too soon. And when they get pregnant, they no longer have breastmilk, and most of our traditional meals are not rich enough. My mother said, ‘the men would like to believe that they are in charge, but the men also know that we the women are in charge,’ and that’s the deal. You can interpret their behaviour anyhow, but that is what holds them together.

A woman knows that she is in charge because the woman also knows that every man respects his mother. Female power, but they don’t have to express it. It is understood. So, that is the issue of feminism that is coming. They don’t have to assert themselves, they mutually respect one another. So you don’t have to have a female movement against males. That’s how it was. My grandmother said to the meeting of men discussing, “stupid people. Do you think having a vagina is an intellectual disability? You’re wrong.” Of course, nobody could disagree with her. “I know about child upbringing more than all of you put together,” and nobody could disagree with that. So it’s mutual respect.

I was the one who had the right of first refusal to sleep with my father. He would allow me to sleep, but I would wake up in another bed the following morning. In Africa, polygamy is understood, and people respected the rules and those who participated in it. My father told my mother that he was going to marry another wife, and even till very recently, again, because of this issue that recognizes that a healthy child needs to be breastfed for at least three years. There are instances where wives actually married a second wife for their husbands.

You only have one photograph in your memoir with you, your father and his five wives. What can you tell us about that iconic photograph?

This was taken in Ogobia, 15 miles from Otukpo, which is where the railway line passed and that was where the Igbo photographers was. This was a very special day. The Igbo man rode his bicycle from Otukpo to Ogobia, with his camera and tripod. Nobody went to farm, so we had to get ready for him to come. That was the event of that day. Everything here was prepared for, waiting for the Igbo photographer to come and take, and he had his camera, and those days, he would take the cover off the lens and count a few numbers and put it back, and then he goes away and comes back about a week later with the print, and it was a celebrated day. It’s a very historic picture. That was how it was done.