‘Why I write? You might as well ask me why I breathe!’

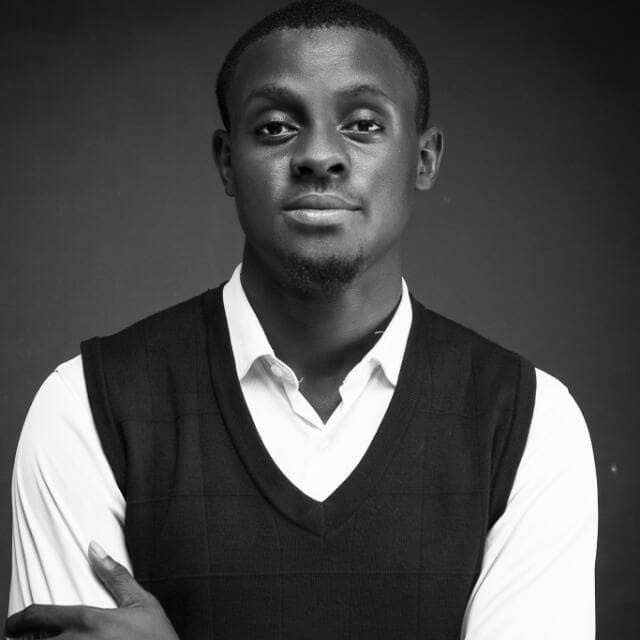

ANAELE IHUOMA is a consummate writer whose works interrogate how the past bears witness against the present and how humanity tends to be poor student of history and so blunders on in spite of resources at his disposal. In this interview, he explains how his work Imminent River is a testament to man’s feebleness and the quest for a society where justice prevails

How much would you say The Nigeria Prize for Literature has energised writing in the country?

Greatly. Just check out social media: you’d marvel at the number of writers’ groups and forums that are established and aspiring Nigerian writers have formed or joined. A great majority of them are in it to improve their craft, as they engage with known writers and up-and coming ones. I believe that, across society, the whole dynamics is changing. Parents who had hitherto balked at their children’s engagements in writing now actually encourage them along that literary path as they see the likes of Tade Ipadeola, Chika Unigwe, Soji Cole, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, Jude Idada, and other – if you like – pen-made men and women. And it’s not just about the official winners; everyone who has been galvanised to strive to improve their craft is already a winner, after all tomorrow beckons. Neither is it about literature as a main career choice; many people from other works of life such as engineers, lawyers and medics (the latter having formed an eternal fraternity with writers, have produced some of literature’s best works – Anton Chekhov being a case in point) have moved from mere dilettantes to the mainstream in their writings. This is happening everywhere in the world, but, I believe, more so in Nigeria, and I wager that The Nigerian Prize for Literature sponsored by Nigerian Liquified Natural Gas Limited (NLNG) has much to do with the trend.

Where were you when you heard the news that you had been shortlisted for the NLNG-sponsored The Nigeria Prize for Literature 2020?

Right in my parlour. It was a Sunday afternoon. I had just come back from church and was trying to read up on social media when my phone rang; it was from the writer Iquo DianaAbasi, one of my favourite poets but one with whom I do not recall ever having spoken on the phone before. The manner I leapt for joy as she broke the good news made my daughter, sitting by, run up to hug me even without knowing what the news was all about; a hug that only tightened when I, in turn, broke the news to her. The whole family then embarked on a spontaneous dance-and- songs festival of praise to God.

Why do you write?

Why I write? You might as well ask me why I breathe!

What would you say writing has done for you and what do you hope that writing would do for you?

Writing has not just done something for me, it has, in a sense, actually made me. Here, I’m not just talking of my current position on the social ladder. I’m talking about self-discovery, about a re-awakening to a reality beyond materiality, about a reappraisal of the universe and of one’s place in it, about social relationships, about redefinition of values – social, cultural, political, etc; of the very essence of existence. Fact is, to write, you must read: that is why we are often described as ‘bibliophile’ – lover of books. You don’t love books just so that you collect them and display them as artefacts or library ornaments, you read them. Often this is inconvenient and may even cause friction in the family, as it may not pay the bills, at least not in the interim, but it has become part of you. The sum-total of your readings and writings is what goes to define and redefine you. Going forward, I hope and pray that writing would give me a bigger reason to want to continue to write. That I would go beyond what Abraham Maslow classifies as biological needs, to instead, scale needs of a higher order. Add value to other people’s lives. Engage in problem-solving on a higher level. Make global impact. And I would like to focus on the novel and drama, two genres that might point their practitioners to the cinema industry, perhaps the non-glamorous niches across the value chain.

Why do you think your book should be the one that emerges winner of the prize?

Well, first, please join me to pray that I win! Honestly, one beautiful thing about The Nigeria Prize for Literature is the administrator’s avowed commitment to excellence as the overriding criterion for winning, which explains why, in one particular year, the prize was not awarded, as none of the books was found worthy. And so, if Imminent River should emerge winner of the prize this year, it should be for no other reason than that it was adjudged primus inter pares, first among equals, in a field that has been described as an “excellent list.”

What do you hope to do with the USD$100,000 money that comes with the prize.

Quite a lot. First, as I write, I am at pains trying to come to terms with the fact that I am unable to take up an MFA Creative Writing offer at a North American university because I cannot provide enough evidence of funds for my Form I-20. Perhaps even more important, it will position me well to take adequate care of my health and my family’s. And to think that this was a deferred admission carried over from the 2019 admission cycle, for the same reason! So, you can see that I will not have to construct Invitation-To-Tender billboards for the supply of ideas for judicious use of the prize money – if and when it arrives. But then, as our people say, one should not start preparing stew for the eating of a bird that is still perched on a tree. Now is the time to mix dreams with prayers.

How does you book reflect contemporary challenges and what ways do you suggest out of them?

Nigeria’s, Africa’s and indeed, global contemporary challenges are multi-faceted. Does Imminent River reflect them? That is for the reader and critic to say, not me; I’m just a poor story teller! But I can tell you that at the presentation of the book in Port Harcourt in 2019, a panel of discussants that included no less a personality than my own teacher, Dr. Obari Gomba of the University of Port Harcourt, (yes, I learnt writing from him), drew interesting parallels between the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade aspects of which are recounted in the book, and contemporary slavery in its various morphs. Is injustice a contemporary challenge or one that has menaced the world ever since Jacob upstaged Esau with their mother’s apparent complicity? If the healer Daa-Mbiiway had been allowed to flourish, would contemporary health issues like cancer, ebola and even Covid-19 have met their match in the ageless healer? I do not know. Neither would I claim to know the ‘ways out’. All I know is, as Franz Fanon says in The Wretched of the Earth, “Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it or betray it.” But mind you, when he said that, neither Virgin’s Richard Branson nor Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had breached the Karman line into weightlessness in space. It’s still a Huxlean brand new world.

What vision of society is espoused in your current work?

Frankly, I did not set out to espouse one vision of society or the other, but to tell a story, one that is worth the reader’s time especially in an era like ours when time itself has become a huge resource. But because we live in a real world, not a fictional Republic of letters, because some of us can relate with a world in which bread is sold not in loaves but in glorified crumbs, where tooth paste tubes are cut open after all the paste is squeezed out, to access its tiniest nooks, where pregnant women declare force majeure in the labour ward because they/their husbands cannot pay delivery charges, etc, – because of these and other seasons of deepening anomy, our books sometimes come out showing the social question-marks you tried to hide. As a writer, your hope is that the reader enjoys the story while the critic grapples with the question marks.

That said, I suspect that a keen critic, after reading Imminent River, might claim, perhaps justifiably, that beneath the main story and its supporting cast could be found, the vision of an egalitarian society, ultimately. Another may see the triumph of true love over evil machinations, as possibly exemplified by the Ezemba/Agbonma love story. Another may hear a cry for the entrenchment of a society of laws. The sage Chinua Achebe asserts that the problem with Nigeria is purely and simply the problem of leadership. Without a scintilla of doubt. However, this postulation can even be further broken down, via what could be its converse, to wit: the solution to Nigeria’s problem is the will to make and enforce good laws across all segments of society. In Imminent River, the court verdicts involving Chief Ojionu and Ezemba’s family could be seen as a travesty, one that sets up a back-to-the wall situation from which civil society recoils, and then things begin to take their natural course.

Who and what are your influences?

The world is my influence. I was born into stories. I shared my growing up years between my community, Okpofe and my maternal home, Eziudo, and embraced each community’s Abigbo story-music-and-dance traditions. It was the story bit that had the lasting impact. I was still an ingenu when I was escorted by my uncle to school. Being the very first set to enter the university through JAMB, I had forgotten that I took the newly introduced matriculation exams and had to be reminded that my name was published in the newspaper. That was the prelude to my sojourn in the cradle, Ile-Ife, where – to answer your question – I met him, not Stratford-upon-Avon’s William Shakespeare, but our own Wole Soyinka; the one who says when you see an elephant, the tamer of the forest, you should not just say “I have caught a glimpse of something’. Now ask me again about my influences!

0 Comment

Imminent River is a must read. I’m sure Anaele Ihuoma will be coming home with this prestigious prize.

Congratulations in advance to the great writer Mr. Anaele Ihuoma. More Wins.