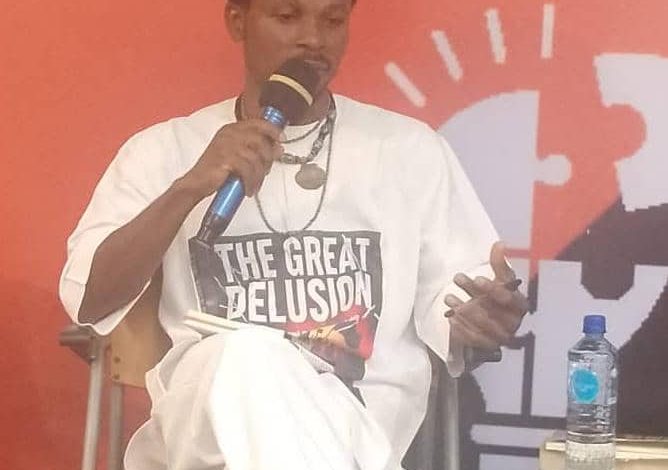

We’re reconnecting from where the colonialists disconnected us from our history, says Oriiz

* ‘Nigeria does not have an art economy’

* ‘We set out to retail, democratise our history’

By Anote Ajeluorou

In this interview, Oriiz U. Onuwaje speaks about documentation as the gap that needs to be bridged before art in Africa can be accorded its due value that is at best arbitrary at the moment

PEOPLE buy and sell art, but when you talk of an art economy, it’s a whole ecosystem, and it doesn’t exist in Nigeria and much of Africa. You have the artist. And you have the financial system that will include insurance. (Which artist or gallery insures their works?) You have proper auction houses where art can be exchanged, like goods and services. You can convert art to cash. All these things do not exist. And the bedrock why they do not exist is simply documentation, because how does the insurance company know that the Enwonwu (art) you’re carrying is, one, authentic and two, valued at so-and-s? What is its value? Those are the kinds of things that determine how much it will be insured for. Once it’s insured, banks will look at you.

But we cannot do all these things because of sharp practices and XYZ that’s being done in the system. What we have now is paddy-paddy art sales. So, because it’s your child who’s the artist, I tell my company I’m buying it for N50 million, but you take N25 million, and I keep N25 million and everyone goes home happy. So, what’s the value of that art? It just dies, because tomorrow nobody else will buy that art, because you do not see the value. Everything revolves around paddy-paddy. If you’re an art critic, somebody will consult you and say, ‘is this an Enwonwu? Is this a genuine Ife head?’ Or an insurance company will come to the art critic and say, ‘somebody has brought an Enwonwu here, is it genuine?’ And because they know you’re an expert in the field, they will pay you for that service of authenticating the art. That’s how an art economy works.

At some point, the artist who is producing a work is not looking for a road contract, because he’s contented just working in his studio, because he’s got value. He can pay his rent, can build a house, and send his children to school, because the system is organsed. I’m not saying organised to a point where it becomes like the stock exchange; no. Look at the art being sold at Lekki market; some of them are valuable but we have consigned them to Lekki market and lowered their value. If you look at art economy in West End in London, UK, some galleries have been there for 50 to 60 years. You have some artists in Nigeria, if you asked them, ‘how many works did you do 10 years ago’, they don’t know.

And like they say, we have the real McCoy; the art economy no be here (small) oo, no be beans. Our mission is, how can we make us know what we have? These are all the things that we want to create awareness for everybody to know. Today, the interior decorators sell more art than galleries. They’re selling art as pictures, not as arts, pictures to match house painting.

Art is not sentiment or emotion, but evidence

ABOUT 33 years plus ago, I was the third largest art dealer in Lagos after Kofo Abayomi and Sheinde Odimayo, and I found that the issue of value was neither here nor there. It was arbitrary, who you know. I’m not saying we should sell art like Bournvita or sunlight soap, but there should be some economy around art – we have people, artists that should be in grades; that’s how to sell art. But now it’s all over the place.

And I said to myself: the only way you can really talk about value is when you have the right documentation, and there’s no proper documentation of art in Nigeria. And so let’s start from the very beginning: proper documentation, which is 8,000 Years of Art in Nigeria. But it wasn’t always 8,000 years of art; at a stage it was 6,000 years of art, because I’d not heard of the Dafuna canoe excavated and carbon-dated for 8,000 years in Yobe State. Once I knew that I adjusted my stuff and started gathering materials for 8,000 years of art. But as we progressed, I found that it was too big a project to just enter into.

Then I tried the museum directly and part of the marketing and presentation which I put down years ago was The Harbinger series, a series of small publications, to be able to, as we say in Nigeria, ‘wet the ground’, to get people to understand what is it that’s coming. A series of four books, which is basically like small report cards, of how I’m collecting materials for the big book.

The Harbinger: A strategic documentation

THE presentation of The Harbinger follows a strategy developed years ago to, as the saying goes in Nigeria, ‘wet the ground’—priming the audience for a forthcoming major publication. This four-part series serves as a set of ‘report cards’, documenting the rigorous process of gathering materials and research for the final book.

The series is structured as follows: The Harbinger 1: Developed over the last six months, this phase utilises objects and historical assets from the National Museum, Lagos (Onikan), as its foundation. The Harbinger 2: This instalment focuses on museum-grade archives and the evolution of “newer” art, specifically examining movements from the early 1900s. The Harbinger 3: This volume offers critical commentary on art valuation, the role of art in public spaces, and the essential frameworks for appraising work. The series is underpinned by the philosophy that no artist exists in a vacuum. Whether in painting, sculpture, or any other medium, every creator is rooted in a specific historical lineage. The Harbinger provides the necessary documentation to move beyond insular perspectives, ensuring that every work is assessed within its proper context.

The evidence-based approach to art in Nigeria

IN evaluating historical masterworks, there is often a reliance on sentiment; however, the art economy is most effectively sustained when driven by empirical evidence rather than emotion. Authenticating a work by a master such as Ben Enwonwu, for example, requires moving beyond anecdotal verification. True authentication relies on rigorous technical and forensic scrutiny, utilising specialised research and scholarly documentation to establish a work’s legitimacy.

By prioritising these objective standards, the project draws on high-level expertise from leading authorities across various disciplines. A central component of this effort is a definitive paper by the prolific art historian Professor Chike Aniakor, contributed to the landmark publication 8,000 Years of Art in Nigeria.

This project is grounded in the principle that no artist is insular; every creator—whether a painter or a sculptor—emerges from a specific historical and cultural lineage. The resulting book moves beyond sentimental narratives to provide the documentation, provenance, and technical analysis required for the professional appraisal of Nigeria’s artistic legacy. It is a work intended to stand as a definitive source of scholarly authority and national pride.

Oriiz U. Onuwaje

Retaining, democratising history, in motion

‘THE unBROKEN Thread: History in Tiny Bits’ is what I’m using to reach across all demographics. That’s why I have 1,000, 1,200 word essays on oratureafrica.com. But what I’m selling to the world on social media – Instagram, X, Facebook – are poems, one minute-long poems that come with videos that will interest everyone. They’re about history in continuum. The caption for today’s poem is, ‘Interest-free Energy’; it’s attractive enough for everybody. What I’m saying is, ‘we don’t borrow energy/ we generate energy/ we don’t ask the world for permission/ we set the rhythm/ sound is presence/ rhythm is proof, even under pressure/ we rise in sound and the world moves.’ That’s dance that I’ve tried to express in a dance video and poem, so that the younger ones can just look at it in a flash. At some point, they’re going to ask questions: where is this going to?

And the idea of this book, for example, is for me to raise money to do the next one, the next one until I get to the big one, and by the time I get to the big one, by the grace of God, the positioning of what we are dealing with now is to get the Federal Government’s attention, not because of paddy-paddy, but because would have been able to bring it to the fore, that this is important. So, the book, 8000 Year of Art in Nigeria, is going to be big. Once we are able to sell 10,000 copies in first two years as coffee table book, then we break it down in Kindle and other price-friendly formats for everybody, because that is the retailing of history, democratising of our history. That way everybody can get it. That’s why we are cutting history in bits.

If you go to my Intagram, WhatsApp, Facebook channel and TikTok pages, oratureafrica.com, everything is there. And we get so many responses. From my one-man show, I’m putting history on the phone for everyone to access, and people are reading this and they’re listening to Burna Boy or Fela; there’s a mix there. For next week, I wanted to do ‘Nok and Architecture’, but I decided to flow with the musical strain. So what I did is ‘Dance with History’; the focus is on dance, but we’re still talking about history. Michael Jackson and James Brown are black people like you and I. What I’m trying to say is that what Ayra Starr does is inside DNA; you can’t but it but only inherit it. And where does that go? It goes back to history. I’m telling you that our sound, because it’s in our heads, the colonialists could not take it away.

Now the goal is to sell art; the goal is the value of art; the goal is documentation and all of that. On paper, those things are great. But how do you connect to that 15-year old child on the streets? Let them hear Ayra Starr. What is Ayra Starr in this place? It’s history; then it makes sense to them. It’s mix and marsh; it makes sense that way. The depth of what art is means we can connect it to any and everything. So we have The Harbinger 1, 2, 3 to 4; then the big one: 8000 Years of Art in Nigeria.

African art as design-thinking and archiving

THE historical narrative often suggests a lack of records on the African continent due to the absence of Western-style written scripts. However, Africa’s artistic output constitutes a sophisticated system of documentation. Works such as the Ife bronze ‘Ori Olokun’ are not merely aesthetic objects; they are high-fidelity portraits—meticulous acts of archiving specific individuals and historical moments.

The architecture of memory

THE Benin Bronzes, including the heads of the Obas and the Iyoba (Queen Idia), represent a tradition of record-keeping rather than random creative expression. Colonial perspectives often severed these works from their original purpose—design-thinking and problem-solving—relabelling them as “fetish” or purely religious objects. Much of what is now classified as “ancient African art” originated from a secular need for functional design.

Functional innovation vs religious misconception

A significant portion of historical African artefacts was not intended for shrines or worship. As evidenced in The Harbinger, items such as lidded containers for kola nuts demonstrate a sophisticated approach to functional design and domestic utility. Although many of these pieces were preserved in royal palaces, their primary purpose was to solve specific design challenges.

Reconnecting the Lineage

THE contemporary task is to bridge the historical gap created by colonial narratives and reconnect with this legacy of problem-solving art. This innate design capacity is evident today in the natural artistic intuition of young people, reflecting a “DNA of design” inherited from a vast ancestral lineage. By viewing these artefacts as archives and engineering, the narrative shifts from the “dark continent” to a history of visible, tangible records.

* Onuwaje (Oriiz)—an artist, dealer, and documentarist—seeks to establish premium value for African art through critical documentation that bridges the historical fragmentation that devalues the continent’s output as “accidental genius.” By “retailing” African history for mass, everyday consumption through restorative publications—including The Benin Monarchy: An Anthology of Benin History, the first of the four-part The Harbinger series, and the forthcoming 8,000 Years of Art in Nigeria—he affirms the African creative legacy as a sophisticated, multi-generational continuum accessible to all