Musing on mental wounds in Kekeghe’s ‘Broken Edges’

By Edafe Emmanuel Erhijodo

“A thoroughly sick community regards the fertile minds as insane and wrecked.” Those are the words of the protagonist, Ejaita, a cerebral young man caught in the maelstrom of failed governance. Set in Imode, an oil-rich community in Africa, Dr. Stephen Kekeghe’s impressive sophomore dramatic piece Broken Edges scours a salient yet disturbing motif often ignored in Africa – mental illness. The story of Ejaita, a brainy chap who exhibits uncanny chutzpah, is one of anguish caused by a dysfunctional and failed government. Like many young people in Africa, Ejaita exudes uncommon sagacity and courage but is soon swallowed up by the quicksand of bad leadership.

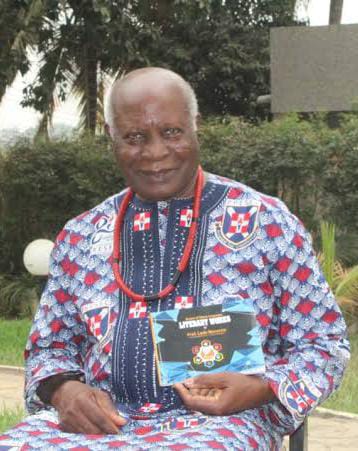

In this theatrical piece, Kekeghe who won the 2021 ANA Poetry Prize with his collection, Rumbling Sky, came fully formed as a master playwright by blending poetic aesthetics and dramatic forms in a flowing symphony. By organically weaving realistic poetic dialogue, he succeeds in adding his name to the tradition of poet-playwrights such as J.P. Clark, Tanure Ojaide, Niyi Osundare, amongst others. Kekeghe, who is Head of Department of English, Ajayi Crowther University, Oyo, brought his years of intense research in mental health into play in this drama piece. Perhaps, the crafting of the plot stems from his scholarly enterprise in exploring the psycho-social and traumatic impact of bad government as the play distinguishes itself by examining the consequences of dysfunctional governance which makes institutions of higher learning churn out half-baked graduates, and without plans for a sure future for them. This is one of the many issues Ejaita’s mother, Madam Gold, has with her son – his inability to secure a job after years of graduation from the university.

Broken Edges is not necessarily a denunciation of government or a scathing and vitriolic indictment of constituted authority; rather, it opens up a conversation and makes a fairly precise statement about the diurnal experiences of young men and women whose collective destiny is at stake. Staying true to his nature, Kekeghe is not afraid to indict anyone enmeshed in the complexity. In the play, he exposes parents who have failed in their duties at the home front, university dons, self-styled public intellectuals, the military, as well as traditional rulers who are colluding with the oppressors to hold the people under jackboots. The play assumes more stature when its historical context is considered – the disillusionment, the military history of subjugation, the failing democratic system, the corrupt traditional institutions, dysfunctional families and other factors that gave (and still give) rise to massive depravity.

The family unit in nation-building is highlighted by the playwright. He sees it as the nucleus of society. Therefore, one can argue that Ejaita’s mental breakdown is not solely caused by the disintegration in society that leads to the death of his best friend, Ederah, but also because of the ‘war within’ in his home. It is a truism that when one is bruised and battered by society, the family unit therefore serves as a place of refuge. Perhaps, Ejaita’s insanity is partly predicated on the absence of this. When he was brutalised by society, he could not enjoy a peaceful atmosphere at home, hence the anxiety and mental breakdown. To an extent, Ejaita’s insanity also represents a microcosm of the larger society. A lot of people have been mentally impaired by the current happenings in society, and the effect of the quotidian traumatic experiences cannot be ignored. Thus, the memories of those incidents are ingrained and latent in the psyche of the people. This is in line with the traditional model of trauma theory pioneered by Cathy Caruth. While drawing attention to the severity of suffering, Caruth noted that traumatic experiences irrevocably damage the psyche. She observed that trauma shatters identity and exerts a negative and pathological effect on the consciousness. This is observable in Ejaita, as he slowly drifted into the gloomy world of incognizance.

It is pertinent to add that collectively, the transgenerational trauma experienced by the people of Imode cannot be ignored. The town suffers untold hardship caused by insecurity, decaying infrastructure, militancy, poverty, amongst others. No doubt, the memories of those incidents are evergreen as they are being transmitted and passed down to younger generations. This could account for the vicious nature of the youths of Imode who are hell-bent on challenging the commissioner. Perhaps, younger people who never experienced the actual conundrum are traumatised by tales of horrors. This is what Marianne Hirsch (2007) described as postmemory. In light of this, it can be argued that Ejaita and his peers are also secondary experiencers of the traumatic past of the region, yet the mental impact is still as potent as those who fought at the forefront of the agitations in the creeks.

In my intervention at the conference on the Legacies of Violence and Trauma’s Repair in the Global South at Stellenboch University, South Africa, I differed that just like the holocaust and apartheid, the traumatic dust has not fully quelled down several years after militant agitation in the Niger Delta. The ripple effect is still being felt and millions of people are walking around with bottled-up mental injuries. Elsewhere, I submitted that the psychic wounds are passed down to children as tales thereby triggering a transgenerational trauma. The case in Imode is not far from this. The tenacious agitation of the youths of Imode is predicated on their traumatic past with politicians and their traditional ruler accomplices. As the aphorism goes, ‘a person bitten by a snake will be scared of a worm’; the people have heard and experienced firsthand the evil of bad governance; hence, they are ready to stick out their necks to challenge the status quo.

Being a perfect blend of drama and poetry with a sprinkling of well-timed humour, Broken Edges certainly leaves a mark. Kekeghe is able to weave a complex yet compelling narrative that invokes both empathy and tears. The deterioration of the protagonist from a cerebral, vocal and highly spirited young man to a muddled and deranged vagrant is both heartbreaking and compelling.

* Erhijodo is a Doctoral Researcher at the University of Ibadan