Money follows content; unless NTA invests more in content, revenue will keep going to other stations, says Igho

* ‘With Cock Crow at Dawn, I was shooting blindly; first series ever to be shot outside a studio in Nigeria’

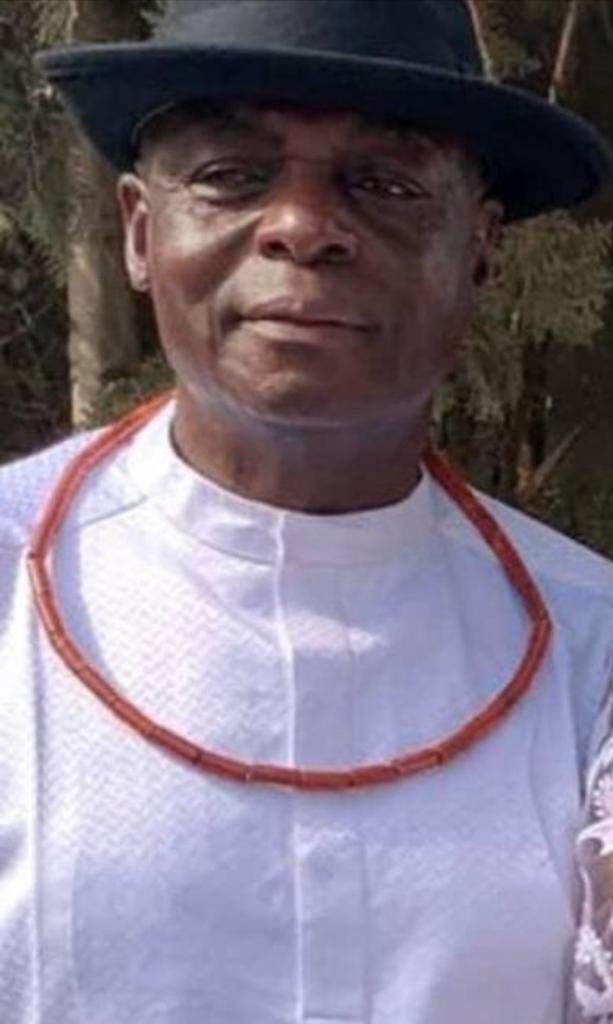

Mr. Peter Igho was a household name in his days when the Nigerian Broadcast Authority (NTA) dominated television broadcasting in Nigeria, especially for his reputation in making such unforgettable drama series like Cock Crow at Dawn and empowering local producers who made many other programmes that stood the station out even as a monopolist. He retired some 16 years ago, but is still involved in he business of making dramas and consulting for radio and television. At his recent 76th birthday celebration at his Lekki, Lagos home, ANOTE AJELUOROU engaged Igho on sundry issues that range from his years at NTA, his retirement, how broadcasting and moviemaking have evolved over the years to where they currently are, and what the future holds for the silver screen. It’s vintage Mr. Peter Igho!

16 years in retirement, you couldn’t be idle. What have you been doing in the last 16 years since retiring from the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA)?

Talking about retirement from NTA in 2008, I left when I was 60, and now I’m 76. I retired from NTA and I now have time for myself. I was employed straight from the University of Ibadan and I graduated in 1972, and the Federal Public Service came to interview people for jobs. I was interviewed and employed and I reported straight to work. So I’ve been working from day one of my graduation and I taught for three years at Federal Teacher’s College, Bida, Niger State. After three years, they stayed in Sokoto. Then, television was under the Northwest states, and they wanted to start their television and I chose to go to television. I was employed formally in television in 1975. When NTA came into being from 76-77, and we all became NTA. I now worked in NTA until I returned in 2008. After that, I set up my own consultancy to help in training people in television broadcasting, camera, production, lighting and all that.

The next year, the president then, Must Yar’Adua sent my name to the National Assembly for employment as the Director of the National Regulatory Commission. So I left broadcasting, and the very next year I became the Director General, and I was there for four years. After which I left better than I met it. When I got there, the office was just a room and parlour and they were not self-accounting; they were just on an allowance, as a department in the presidency, of a hundred thousand naira a month. And when I took over, I moved from the room and parlour to two floors at Maitama. And after that, I moved again to the present five floors in Jabi, where they still are now. I left there in 2013. Before I left, I had opened sixteen offices around the country; Jos, where I was born; Sokoto, Kano, Kaduna, Ibadan, Ilorin, Lagos, Ebony State, Owerri, Port-Harcourt and of course the one in Warri. I employed more than 500 graduates from the 11 staff that I met. I also raised N3.4 billion for the government, which I paid to the trust fund to be used by the government for good causes. Lottery is the act through which people are empowered. When you empower people, the resources used in empowering —whether in cash or kind— 20 per cent of the revenue goes to the government, and it’s that 20 per cent that is N3.5 billion. That would tell you how much we empowered Nigerians by, well over N80 billion. Suddenly, people who where not aware of the power of lottery started eyeing it. That was how I left.

When you say 80 per cent was used in empowering Nigerians, what does that mean?

In every lottery act, 20 per cent of the revenue that comes from every lottery scheme goes to the government. That 20 per cent was the N3.5 billion I left in government account. 50 per cent goes to Nigerians who play it, because it’s their money. So, how much they get, how much they win is what makes them want to play; it’s what they get that makes them want to play, so prizes must be 50 per cent. So if 20 per cent is 3.4, 50 per cent is 3.4 times 2.5 per cent that is paid as prices to Nigerians. But the person who sells the recharge card also gets 20 percent. Then the person who runs the lottery gets 10 per cent. That’s 100 per cent. Every lottery scheme that comes, the money is shared. 20 per cent must go the government; 50 per cent must go to Nigerians who play it, because it’s their money. 20 per cent to the people who make the money, 50 per cent to the people who play and 10 per cent to the person who organizes it. If you calculate 3.4 per cent I left on ground, you can imagine how much we empowered Nigerians.

Mr. Peter Igho

So all these sports betting platforms are part of it?

Yes, because that’s what makes people want to play. If they don’t get money, they don’t play. I worked there for four years, then I went back to my consultancy which I still do. I help people get radio and television licenses, and we still have a production outfit. My son also has his outfit. I’m still very busy in broadcasting

You don’t look 76 one bit…

I play golf at least three times a week. I believe he who rests rusts, so I keep myself busy physically and mentally as much as I can.

You were part of the NTA boom years, and in the last 20 years or so, the station has been a shadow of itself. Does that look enviable to you as a former helmsman?

As time has gone on, there are more and more stations today. The days of NTA monopoly are gone; there are more stations. But when you look at it, many people don’t understand the whole concept of the structure of broadcasting. So they compare apples and oranges. The NTA is a full-fledged broadcast organization that produces and covers the entire gambit of programming – children’s programmes, women’s programmes, health, cooking, documentaries, drama, news, current affairs. The only station like it is maybe AIT. When people compare NTA to AIT or ChannelsTV; Channels is just a news and current affairs station. You can’t compare that to a station that has different varieties of programmes. If you’re making a comparison, compare the news department of both, because NTA does much more than news and current affairs; it produces drama, documentaries, etc. People say NTA is not as popular as it used to be, but it depends on what you’re watching. Channels doesn’t show dram, doesn’t show documentaries. So what would you use to compare? Most times we analyze and denigrate NTA because of lack of knowledge of what each station is supposed to do.

In terms of eyeballs, what you do is talk to advertisers and they tell you that NTA has a spread that no other organization has. When you want to advertise, you’re looking at eyeballs. NTA has a station in almost every state capital of this country. Channels doesn’t have that. If you want to advertise your product, and you want people in every state to see it, would you put it on Channels or NTA? When people want to denigrate NTA, they fail to understand what is out there and what people want; it’s based on what you want. You may say that in this time and age now, NTA has not been in the top level of programming. What are you comparing them with? DStv? That’s a pay-to-view service. It’s not a public broadcast organisation.

People who criticize NTA say drama was one aspect NTA stood out, being the only station at the time and they used to empower local producers to bring quality contents. Sadly, that’s not the case at the moment, so there are fewer dramas. And for a big corporation like NTA, it has abandoned local producers and what it shows it worthless and that has driven audience away. Why is the station not maximising its spread strength?

In the old days, NTA was known for so many notable programmes – documentaries like Food Basket, Giant in the Sun; dramas like Cock Crow at Dawn, Behind The Clouds, Mirror in the Sun, and children’s programmes like Tales by Moonlight. Now, it’s like NTA is no longer churning out that volume, quantity and level of content. So, compare NTA to itself. You can’t compare it to anyone else? So why is NTA not doing as much as it used to do before now?

Some even argue that they should be competing with the paid television when you look at NTA’s size. Why is it not competing?

Maybe that’s where we should look at. For paid television, Nigerian’s love for the foreign things and readiness to pay for them is a problem. NTA is dependent on its own generated revenue and government’s intervention. You know that things aren’t too rosy for government’s organizations that are funded also by government, and they’re reducing resources that are not available, as it used to be. Right now, must government’s institutions are told to go and fend for themselves. Most times, they don’t have the resources to produce as much quality programmes as they used to be. That’s the problem. And of course, don’t forget that most of the stations that came up after NTA poached staff from NTA. In spite of all that, almost all these stations have people who are ex-staff of NTA, and they’re still on their feet. NTA must be challenged, because as the competition grows, they must know that money follows content. For as long as they don’t do more content, they will lose out in terms of revenue. Unless NTA invests more revenue in content, revenue will be going to other stations. It will be a ripple effect that will negatively impact on it.

So I agree, NTA should do more within the resources they have. Things have gone up now, and you’re paying a producer up to one million naira to produce. How many tickets can they buy to do a production? How many vehicles do they need? They need diesel to run a station. Those costs make it more and more difficult for content producers. That’s the problem of NTA; resources are not there. Of course, and again, many of the staff do not go for training, and it’s getting more competitive out there in terms of quality of training and the more you train the cameramen, producers, makeup artists and all that, the better, because NTA handles more than others. Others just sit in the studio until the days of an interview and talk to cameras, but you have to go out into the field for documentaries, do costumes, pay artists fees and all that. It costs NTA more than anybody to produce quality content. I can only challenge them to do more. It’s tough out there, but when the going gets tough, the tough must get going.

What has been the most challenging thing for you in what you do?

MY family and friends think I’m working even harder now than when I wasn’t retired, because I’m really very, very restless. So many ideas are coming in everyday, I wake up and I’ve got something to do. I’m still writing scripts, working with my son and developing another great series that the world will see soon. And I’m consulting for people to help them set up radio and television stations. I’m full of the joy of spending time with my family, which I didn’t do much of when I was working, and then I have grandchildren now to also contend with. I’m enjoying it, and I’m just happy that God gave me the strength to be able to run around and do a lot of these things. I’m still very busy because I believe that he who rests rusts, and success comes to he who moves. The body is like a house, and if you leave it for a while, it decays; so, you must keep going, and I’m glad that I’m challenged by so many people coming to me that they want to do things, and I never say no. I always ask when and how. I go out and do the best I can. I don’t push myself too much, but at least I’m happy and I thank God for my family and for life.

In your working years, what production challenged you the most, and which gave you sleepless nights and which one did you enjoy doing the most?

To be honest, there are no productions that don’t give you sleepless nights. Most times, when people watch BBC and watch what we do here, and they say, ‘how come?’ The producer in Nigeria has to work 10 times more to achieve, because most times the resources, whether human or material, are not available, so you’re making do, creating ad inventing as you go along. If BBC producer goes out, he has everything thought-out for him – vehicles, equipment and all that. If I wanted to create a movie today and I need a thousand costumes that look like masked men, I just make a phone call to the industries that produce them and I get them. In Nigeria, who do I get to do this? Wen we did Tales by Moonlight, I thought of all those animal costumes and I remembered an artist from Zaria, and I called and employed her, bought her machines and she sewed them for us. There were no companies we could get those costumes from. Tales by Moonlight was unique because it was the first time we were doing that.

The same thing with Cock Crow at Dawn; it wasn’t just the popularity of the programme; it was the challenges. That was the first ever drama series shot entirely on location outside the studio. Before that, it was Village Headmaster, Samanja in the studio, protected from environment and everything in place in the studio. With Cock Crow at Dawn, I had to rent houses and furnish them, get a location, find a stream, and employ staff that would live there. We were not in the comfort of the studio; we were out there in the society creating believable stories among the people, and it was the first ever. When we started, I was shooting on film, that’s celluloid film. There were no portable video recorders, and I had to send the images to London for processing, because there was no laboratory to process them in Nigeria. Then they would call me from London to tell me the quality is good, but they won’t tell me if the acting is good until I get to London, and that’s when I get to know if something was wrong. I was shooting blindly. When we were shooting then, the sound was separate from the picture. That was the challenge and people are not aware.

When people talk about these series, it’s much more than just the content. It’s the innovation that were carried out in that production, all on location, and that is part of it. Of course, the technology we used, it was when we’d shot over 13 episodes before they sent me and my cameraman to London and we learnt that there was a new camera which you can shoot and see what you’re shooting immediately with a monitor. So we were taught how to use it before bringing it back here to use. We shot 13 episodes on celluloid. In the studio, all your microphones are in the right places, but now we’re shooting on the street and there’s a crowd scene, and it’s challenging to record the sound. Cock Crow at Dawn has the best sound because I paid a lot of attention to the sound and I bought all the right types of microphones to use on location.

What exactly prepared you for the job? You said you left university straight into the job. What did you study?

I was born in Jos and I grew up there. My father was a tin miner. Growing up in Jos, there were cinema houses and I always ended up in the cinema and I was always beaten for it. I imbibed the language of the moving image from an early age. Growing up, adults would pay for me to enter to sit by them and explain what was going on on the screen. Even the movies were not in English. The first film that came were American films – Tarzan, Captain America, then the Indian and Chinese films without subtitles, but I could follow all of them. I was able to understand the language of the moving picture. Many years later, when I sit down and read a story, I begin to visualize how I’m going to shoot it. These days, people just shoot at random but I did all that, growing up. When I entered television, I was in charge of drama in 1975. I was shooting and producing English and Hausa drama. I studied Theatre Arts and English at the University of Ibadan, but that is just stage performance and it had nothing to do with television. Growing up in Jos filled me with knowledge of what to do without any formal film education. I sent my son to film school, so from the knowledge he had from knowing me, growing up and watching, he now added that knowledge to formal training. That’s what they do it now.

When you look at the television landscape in Nigeria right now, and Nollywood, what comes to your mind?

Well, it shows that the young shall grow. When we worked, technology was a little different. If I wanted to edit, like when I went to London or later when video came, to edit, you have three big machines. One shows what the tape that’s playing, the second one from which you see what to edit and the third records what you see from both machines. The room is full of those machines. Now, if my son wants to edit, it’s just his laptop and the screen, he would also do all his colour corrections and download all his soundtracks, which would usually take me up to two weeks. Technology has grown and developed, and they’re doing wonders. They’re doing better than we did because they have the facilities. They have the ability to come up with amazing things.

Sometimes, people ask me, ‘how are they doing?’ They’re doing better than we did. Sometimes, they want us to denigrate what they’re doing. No. We did great. But technology has changed, and they’re doing a lot better than we did; they’re doing amazing things. Now, at one point, we used to say Nollywood dwells too much on fetish and negative things, but it has gone beyond that. They used to dwell on fetish and that most Nigerian men turn to snakes at night; that no one becomes rich without going to the babalawo. But that generation of producers is gone. Right now, we are doing things that are realistic, dealing with issues that touch on life; they’re mirroring life in society as it is. With all its warts and all – positivity and negativity, we’re forging ahead. We as producers should be careful about what we show to people, because they will judge us by what they see about us. I was in Maputo and I met someone whose daughter wanted to come to Nigeria, but he said he was afraid for her, because he doesn’t want her to be used for money rituals. I asked where he heard that and he said he saw it in Nigerian movies. Luckily, all that is in the past now. We are doing better and our stories are much more elevating and bring out the humanity in us.