Literature and the Creative Economy: Finding relevance, overcoming misconceptions of book industry’s contributions to nation’s economic wellbeing

The paper examines the concept of the creative economy as arising out of the newfound quest to extract economic values out of cultural and creative activities. The paper goes on to attempt to find the place of literature and the book sector within the creative economies of most African nations ,using Nigeria as a representative example. The findings show that the sector is still a poor cousin to other sectors within the creative economy as its real status as an economic earner is yet to be mapped and potentials yet to be empirically ascertained. The paper goes ahead to proffer measures through which the actual contributions of the sector to the GDP of most African nations can be assessed and enhanced so that it becomes a major player in the diversification of national economic activities

Keywords: Literature. Publishing. Creative Economy. Book Industry. Economic Wellbeing

Introduction

THE global economic downturn of the 1980s necessitated the search for alternative drivers of the economy of most nations. Hitherto, the culture sector from which the buzz of the creative economy has evolved was portrayed as secondary to any economy as it is dependent mostly on public subsidy and never considered as a domain of mainstream economic activity. Most nations in Africa and in other developing economies in the world are largely dependent on commodities and mineral resources to generate wealth and earn income for the sustenance of governance. However, in the last two decades, a broader appreciation of the sector emerged as emphasis shifted to understanding:

not just the traditional art forms, such as theatre, music and film, but service

businesses such as advertising(which sell their creative skills mostly to other

businesses)manufacturing processes that feed into cultural production, and

the retail of creative goods. It was argued that the industries with their roots

in culture and creativity were an important and growing source of jobs and wealth

creation.(British Council,2010).

With this awakening came a renewed interest in concepts like the cultural industries and creative industries as part of the emerging field of the creative economy. This was a time when traditional cultural activities like:

designing, making, decorating, performing-began to be woven with a wider range

of modern economic activities-advertising, design,fashion and moving image media

and, even more importantly, began to be given much greater reach through the

power of digital technology- that was the moment when the ‘creative economy’

most people use the term ,was truly born(BritishCouncil,2010).

In the UNESCO Creative Economy Report 2013 (19),it was highlighted that the need to graft cultural practices into the lane of tangibility of economic gains has given room to the evolvement of buzzwords such as creative economy, cultural industries and creative industries which are used differently and interchangeably in different situations. The term creative economy was said to be popularized by the British writer and media manager, John Howkins, who applied it to fifteen (15) industries ranging from the arts to science and technology. Cultural industries refer to forms of cultural production and consumption that have at their core a symbolic and expressive element and now embraces a wide range of fields, such as music, art, writing, fashion and design, and media industries, e.g. radio, publishing, film and television production. The term creative industries is applied to a much wider productive set, including goods and services produced by the cultural industries and those that depend on innovation, including many types of research and software development. Specifically, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development(UNCTAD):

the creative industries- which include advertising, architecture, arts and crafts,

design, fashion, film, video, photography, music, performing arts, publishing,

research and development, software, computer games, electronic publishing,

and TV/radio-are the lifeblood of the creative economy (UNCTAD,2023).

The creative economy can thus be characterised as the sum of all the parts of the creative industry and has been identified as an economy that “promotes social inclusion, cultural diversity and human development (UNCTAD 2022 Report, 1).

The discourse around the cultural and creative industries (CCI) and the creative economy has evolved over the years to accommodate a new term called the orange economy, which is often used now interchangeably with the creative economy. The term is said to have originated in Colombia to refer to “that sector of economy that has talent and creativity as leading inputs” (Kasim Adoke & Ishaq Saidu,131). Whatever is the referential signifier of the economy under discourse in this paper, they all have common denominators and attributes which are: creativity is involved, talent is of importance, it is knowledge-based, it evolves from the culture of the society and is shaped by it, it can be enhanced with technology like every other thing and it is becoming world-wide the inexhaustible pool for job and wealth creation.

The Place of Literature in the Creative Economy

THE talk about the creative economy foregrounds the necessity of moving away from the intangibility of service or existence to commodification of cultural products or services that can be traded for income generation and wealth creation. Literature as we know it starts from the realm of the intangible; from the creative pedestal involving mostly the individual with no primary inkling of commerce but expression being the guiding principle. It is when this creative expression manifests in written words on paper or the screen of digital devices and is frozen into a form for transmission to others that we have the book or text which is a major product of the publishing industry. Thus, if we are to find the place of literature in the creative economy, the fortunes will largely be tied to books and the publishing industry. Though Africa is largely an oral culture before the coming of the colonialists from the East and West, the book and the publishing industry in Africa has come a long way and has been there all along as a medium of general societal re-orientation and education. The book and the publishing industry has for long been consigned to the realm of the provision of social services with profit not often intended. In the beginnings of the publishing industry in Africa, we find colonial enterprise at the helms with big time publishing houses with ties to foreign capitals being the big players. As expected, whatever economic profits made from these early days of publishing were repatriated away from the continent to foreign capitals. However, in the sphere of literary arts or literature as we may call it, there was an attendant collateral benefits to these colonial publishing enterprise with the discovery of indigenous African literary minds whose writings went ahead to shape African thoughts for many years ahead. The commercial and intellectual success story of the African Writers Series (AWS), published by Heinemann is a supreme example of what the book industry was in that early period of African political independence from Western colonialism. The AWS’s example ensured two things and those were the establishment of a continental wide economically thriving book industry and the cross pollination of ideas across Africa.

Since the demise of the model of the AWS of Heinemann and other such publishing giants like Longman, Evans etc, arising out of the economic downturn that pillaged Africa with the continent-wide adoption of economic structural adjustment programme handed out by IMF and other Bretton wood institutions in the 1980s, the book and publishing industry were hardest hit. Multinational publishing houses closed down across Africa and relocated back to their mother foreign capitals, the educational institutions collapsed, libraries and renowned international book fairs within the continent such as the Ife International Book Fair and the Zimbabwe International Book Fair closed shops, paper mills went comatose and writers and intellectuals (those writing the books that sustained the creative flow into the publishing industry) left the continent, fleeing from dictatorship and other desperate conditions.

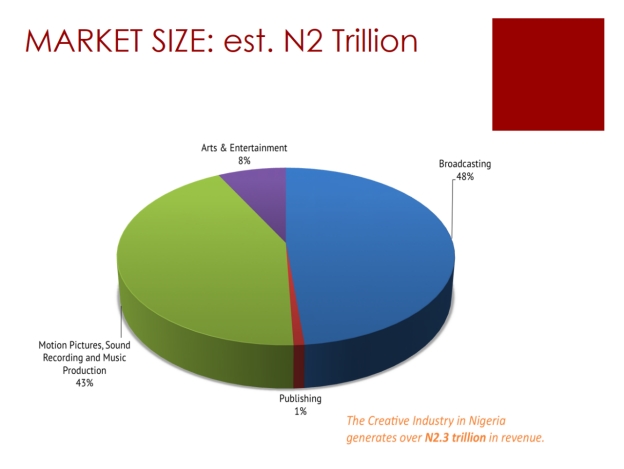

Two decades after the painful and societal debilitating economic downturn in Africa of the 1980s, life gradually returned to the publishing world with local publishers striving to fit into the schema abandoned by the hitherto multinational publishing companies. Then came the period of the Africa Rising Syndrome, with emphasis shifting away from the largely mono-cultural,natural resources -dependent economies of most African countries to the insistent need to mine the creative economy for economic diversification. Africa had to look back to its grand history and cultural heritage to find economic use for most of what it had earlier treated as aesthetic adornments of its historical existence. The arts, culture and tourism sectors became the new avenues for keeping the booming youthful population engaged in productive activities, some of which became exportable in the areas of music, film and broadcast. The publishing industry even in this new found use for the components of the creative economy remained a poor cousin of the other players in that economy. Let us here illustrate with the example of Nigeria and assume that is largely representative of the average situation in most African countries as gleaned from the data presented by Oyebode Akintunde in his presentation at the British Council Creative Industries Conference and Expo in 2016 :

The reality in Nigeria as exemplified in the graph above is that the contribution of the book and publishing industry to the GDP of the country is not that significant. The potentials of the music, film and allied industries in generating foreign exchange and providing jobs for the citizens of the country are well noted within government circles to the extent that government has attempted to boost the hitherto informal sector with all sort of financial interventionist schemes. The popular Nigerian film industry, called Nollywood, which has become the flagship of its creative economy, with its soaring success as the second largest producer of films in the world and a great generator of importable income for its practitioners, has experienced a number of generous government funding interventions such as the N3 Billion Naira Project ACT Nollywood and $200million Entertainment Fund administered by the NEXIM Bank and the Bank of Industry and N1 Billion Naira Bank of Industry Nollywood Fund. The music industry and other sectors in the cultural and creative industries have received similar attention from past and present Nigerian governments and have been featuring regularly in the general discourse of big time public and private sectors players so much that those of us in the book and publishing sectors continue to feel excluded from a place of relevance in the creative economy.

However, a recent search for current data on the general contribution of the creative industries subsectors to the GDP of Nigeria revealed a set of “creative industry factsheet” derived from the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics which revealed that between 2011 and 2020:

the publishing industry showed a gradual progress in its contribution to

the nation’s GDP from the year 2011 and attained its all-time high in the

year 2014 with a contribution of 10.28%. The subsector remains the only

Sector that posted a massive contribution of 6.79% to the nation’s GDP

during the covid outbreak(Akamadu, 73-75).

| Year | Textile, Apparel & Footwear GDP (%) | Art & Entertainment & Recreation GDP (%) | Motion Pictures and Sound Recording GDP (%) | Publishing GDP (%) |

| 2011 | 2.03 | 0.13 | 0.99 | 0.0197 |

| 2012 | 1.99 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 0.018 |

| 2013 | 2.28 | 7.85 | 1.85 | 7.85 |

| 2014 | 3.01 | 10.21 | 10.05 | 10.28 |

| 2015 | 2.78 | 6.54 | -0.9 | 8.56 |

| 2016 | 1.08 | 2.05 | -1.08 | 0.46 |

| 2017 | 0.82 | 4.13 | 0.57 | 2.29 |

| 2018 | 1.69 | 2.53 | -0.44 | 6.03 |

| 2019 | -0.09 | 4.12 | 0.2 | 2.6 |

| 2020 | -7.06 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 6.79 |

(National Bureau of Statistics, 2011-202

According to the said “creative industry factsheet,” the publishing industry contributed the highest to the GDP within the cultural and creative industries (CCI) sectors in the years under review and while other subsectors nosedived during the 2020 pandemic year, it maintained a kind of resilience as its contribution rose further. This set of current data which contrasted sharply and positively for the publishing industry against the earlier data referred to and the negative widespread perception of the industry’s contribution to the national economy within and without, has therefore made it imperative for the importance of the industry to the economy to be properly reappraised.

The Book Sector in the Creative Economy: Finding Relevance and Overcoming Misconceptions

AS a member of Council of the Nigerian Book Fair Trust (NIBF) , an organization comprising of all the major stakeholders in the Nigerian book industry years , between 2015-2019, i can surmise that the book industry has been one that has not received the required attention from the government, in spite of its contributions to the knowledge and creative economies. NIBF has been organising the Nigerian International Book Fair, touted as “the biggest book fair in Africa” (Oluwatuyi,2023), annually in Lagos for over 20 years running, and in spite of the successes recorded by this fair in creating local and international markets and network of engagements for the players of the book industry, it is still hankering after non-existent, lukewarm and rather indifferent government participation. Every year, the Trust tries its best to draw the attention of the relevant government authorities and agencies to its activities without success. This situation led the board of the Trust to think of commissioning a study of the contributions of its annual book fair to the creative economy of the hosting State and the income it generates yearly for the participating authors, publishers, book sellers and advertisers, who attend from different parts of the world. In essence, it came to a point in which there was the need to prove the relevance of the book business in factual economic terms to the creative economy in order to be taken seriously by government and policy makers. Governmental and political neglect of the book and publishing industry within the creative industries as understood by policy makers surfaced during the covid 19 pandemic period when the government initiated discussions with the stakeholders in the industry with a view to give them palliatives but left out associations and guilds within the industry. It took a collective reminder letter from the associations within the book and publishing sector before they were accommodated in the discussions, which at the end never manifested in any measure (Oluwatuyi, 109). The overlooking of the sector by government at all levels when the talk is about engaging or giving assistance to the subsectors within the creative economy is a recurrent feature in the Nigerian public space.

Taking a close look at the publishing industry and the book market in Nigeria, it would be discovered that beyond the commodification of its products, it has consistently been connected to the building of the cultural capital and advancement of education in Nigeria. The publishing industry and the book market cannot be divorced from the huge education industry spanning the primary, secondary and tertiary levels. Servicing of the education industry with required books has given rise to a crop of educational publishers who are mainly devoted to the publication of texts for the schools curricula. This set of publishers with their strategic connections to the educational regulatory authorities, who prescribe texts for schools, have been able to remain profitably in business, employing many and keeping the wheel of their publishing economy running. Other kinds of publishers focusing on general interest books have risen which each capturing its targeted slice of the market in line with identified publishing predilections. Thus we have in Nigeria now, like we may have elsewhere, publishers of children books, religious texts, academic texts, literary texts, aesthetically packaged texts, biographies and political books etc. Each of the major publishing houses has found their niche and has maintained their peculiar competitive advantages.

Publishing clusters have risen in the country around the Ibadan –Lagos axis where the dominant publishers are located and where the machines, know-how and labour are available. The publishing industry can be said today to be stable, though in dire straits with the absence of favourable environment for its production albeit with the infrastructural and power deficits facing the nation and with its not near optimal capacity in terms of the consumption of its products. The book sector is still over-dependent on imported raw materials and operates in an atmosphere of lack of a functional national book development policy and poor reading culture. The book sector as it is today has no identified strategic linkage with the other sectors of the creative economy such as the film industry and is still heavily dependent on its traditional distributive framework, in spite of the advancement of digital technologies in the larger society. The industry in the absence of its identification by government as central to the sustenance of the nation’s cultural and intellectual capitals has not enjoyed any special protection from the ills of piracy nor the facility of focused funding intervention.

To bring the book sector and the creative producers in it into proper reckoning as contributors to the general economic well-being of the nations and countries of Africa, the following measures need to be taken:

- Each country should embark on a research-based mapping of the publishing and book sector’s contributions to the national economy in order to establish the real contribution of the sector to each nation’s GDP. It has been noted that reliable data about the state of book publishing does not exist in most countries of Africa except for a place like South Africa and Morocco(Hanz,24).

- To remedy this absence of data on book publishing and the publishing sector generally, each country of Africa must pay attention to the maintenance of an up to date national bibliographies through their various national libraries.

- The stakeholders in the sector should put pressure on governments to enact and implement functional book development policies that will help in enhancing the economic potentials of the sector.

- Through the agency of the African Union, other continental-based regional bodies and national governments, attention should be paid to supporting the national aassociations of writers and other subsectors within the book chain within the continent who are presently keeping the publishing sector vibrant with various intra-national and international literary activities such as capacity building workshops for writers and others within the book chain, organization of book fairs, literary festivals and the administration of literary prizes.

- The African Union and other regional bodies should think of establishing continental wide and regional literary prizes of great merit and integrity to encourage literary creativity and publishing within the continent.

- Circulation of literary materials across the continent from one part to the other should be encouraged to create understanding and cement the spirit of Pan-Africanism. This dialogue across nations and cultures through the circulation of literary texts, which hitherto existed in the hey days of multinational publishers, should be brought back with the coming into being of a scheme to ensure continental wide publishing and distribution of books.

- The organization of major book fairs and literary festivals in each of the regions of Africa should be encouraged and sustained as these are the present platforms in which the contributions of the book sector to the economic growth of African nations can be readily measured.

- There is a lot of residual income to be mined from the protection of intellectual property and establishment of collecting societies to collect and distribute income to right owners for the use of their intellectual property. This is important with the advent of the digital age with growing interest in e-books and e-publishing.

Conclusion

THE book sector remains one of the most resilient sectors of the creative economy of African nations because of its ties to educational development. However, it real contributions to economic growth of nations has been taken for granted and undervalued because of the lack of empirical data and due to the perception of the sector as belonging to the realm of social service rather than that of economic activity. With the imperative for the diversification of most economies of nations in the continent, the sector has grown enough in status for a thorough self-appraisal towards tracking its economic potentials and enhancing its capabilities as a major contributor to general economic well-being of nations within the continent.

* Being a paper presented by former federal culture director, Mallam Denja Abdullahi at the international conference of the Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization (CBAAC) held from January 11 – 12, 2024 in Lagos, Nigeria