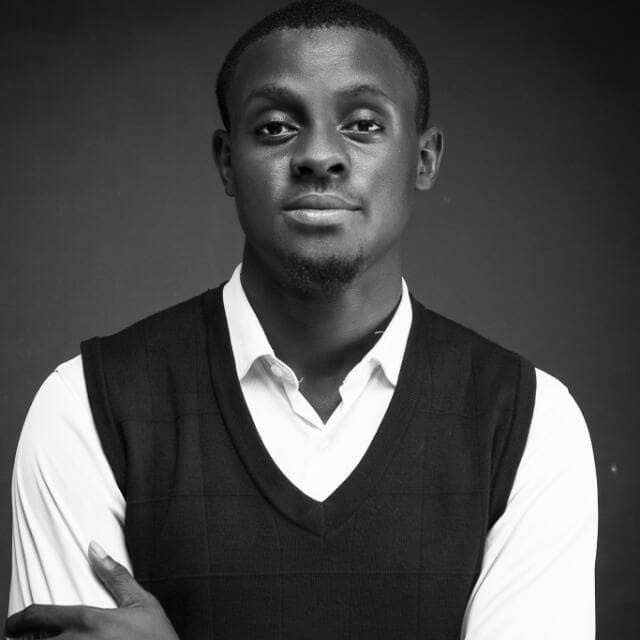

‘I’m of Achebe’s school which premises that works of art should not be innocent’

OLUKOREDE YISHAU’S In the Name of Our Father takes a dig at one society’s recurring malaise: religious charlatanism, arguing that his art is on a mission to make society better. He’s in the race for The Nigeria Prize for Literature 2020 USD$100,000

Where were you when you heard the news that you had been longlisted for the NLNG-sponsored Nigeria Prize for Literature?

I was in my apartment in Ilupeju, Lagos that Sunday when Toni Kan, who was the first editor to work on the book, and Jude Idada, who won the prize last year, broke the news to me and became the astronauts who took me to the moon.

What would you say writing has done for you and what do you hope that writing would do for you?

Writing has won me admiration. In the Name of Our, Father is particularly popular among students and lecturers in some departments of English and Mass Communications in Nigerian universities because we got some sponsorship to donate to them over four thousand of the book and a number of students have used the book for their BA and MA theses and at least one person contacted me that he was using it for his doctorate degree. So, I have some following as a result. With the nomination of the book, more people have come to also know me and I believe with time, writing will do more for me. I’ve also been invited to ghost-write and got paid handsomely for it. I also look forward to writing giving me international repute.

Why do you think your book should be the one that emerges the winner of the prize?

This is a difficult question and really my opinion does not matter. If this were a campus election and we were doing manifesto night, I would have spoken about how well I pulled through the story-within-story technique and how I was able to link the two stories that make up the book very well. Unfortunately, no amount of campaign or elucidation from me will affect what the judges will do. So, I’ll rather leave them to pick their choice while hoping that the pendulum does not swing away from me. And as someone who has read 10 of the 11 books on the list, I know they are all good and it can go anyway.

What do you hope to do with the $100k amount that comes with the prize should you win?

It is difficult to spend money that you’ve not earned, so I find it difficult to answer this question and the truth is that whatever I tell you here will not have much impact on what will happen when or if the money comes in. So, let’s see what happens first and the muse will direct me on how to handle the issue.

How did the CORA/NLNG Book Party in your honour come across to you?

The book party was a good idea and I had a good time and felt on top of the world seeing my face splashed on fliers and posters and the backdrop of the podium. I also enjoyed the conversation and the opportunity to talk about this book I wrote in 2002 as a 24-year-old boy.

How much would you say the prize has energized writing in Nigeria?

I think the prize has encouraged more people to write, especially poetry, children’s play, and drama. The novel form has always been thriving, but with the award, more people are seemingly also writing in these other genres. Of course, it can always be better and one area I think the organizers can work on is the acquisition of at least 1,000 copies of all the books on the longlist for distribution to readers across the country. If the book gets on the shortlist, more copies should be acquired and more copies of the winning book should also be acquired for distribution, so as to make the book more popular.

How does your book reflect contemporary challenges and what ways out of them?

My book is as contemporary as today. In this age where we have so many charlatans on the pulpit, my book’s relevance is undoubted. Also in an era when so many of us are frustrated with the political elite, my book is one that will remind us that military rule is not an alternative. So many social ills addressed in the book are also still with us, such as contractors getting paid for jobs not executed and other forms of corruption.

What vision of society prompts you to write?

I belong to the (Chinua) Achebe school, which is premised on the fact that a work of art should not be innocent. My books are guilty because I am not an apostle of art for art’s sake. I practice what I call art for relevance. My art is relevant and my stories are sourced from the streets, from the villages, from the towns, and from the shanties. At times, I also cross beyond our shores to get materials for my relevant art.

Who and what are your influences?

I’m sure the number one influence is Chinua Achebe. The opening line of my novel, for instance, is something that can remind you of Things Fall Apart. I’ve also studied the works of great literary minds like our own Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Maik Nwosu, who was my boss at the time I wrote In The Name of Our Father. I read widely and I must have picked one trick or the other from these writers and they must have influenced me even in ways I can’t tell. This year alone, I’ve read close to 70 books. What I write is also strictly guarded by the need to address some issues germane to human existence.