‘The Harbinger’: Oriiz delivers blow to accidental art genius ascribed to Africa’s sustained intellection

By Anote Ajeluorou

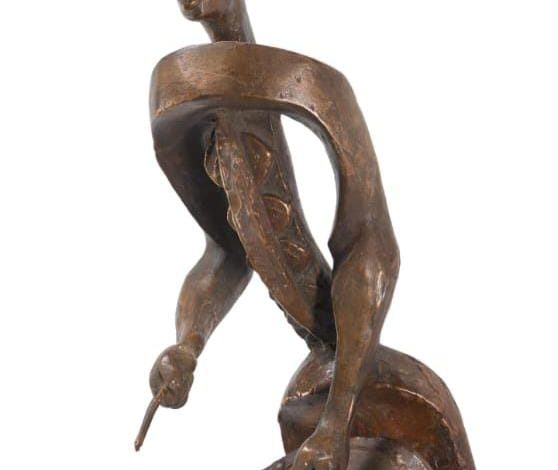

BENIN bronzes and ivories. Nok terracotta. Ife bronzes. Igbo-Ukwu bronzes. Ekpo masks. Wooden masks of Niger Delta people. 8,000-year old Dafuna canoe wonder. Modern art in Nigeria. All products of sustained artistic genius and intellection, from ancient to modern, but denied by jaundiced western cultural gaze. Just where does genius start and end among a people in one long continuum of history? And how does intellect suffer discontinuity to be considered fragmentary and accidental? And how can the genius of intellect be threaded together into one historical continuum to create a wholesome reconstruction of memory needed for a people’s healing? These are some of the questions that Oriiz U. Onuwaje poses in his new work, The Harbinger (Crimson Fusion, Lagos; 2025). It’s the first part of a work that dovetails into his forthcoming magus opus, A Window into the Soul of a People: 8000 Years of Art in Nigeria.

Rather than help, Africa’s encounter with the west became a bump in the continent’s historical march to the future, and as Onuwaje puts it in the prologue to this important book, “For more than a century, Africa has been presented not as a civilisation with continuity, but as isolated marvels. A Nok head in one museum; an Ife portriat in another; a Benin bronze displayed in a city that has no cultural memory of how it was made. Each object is treated as an artistic miracle without ancestry.”

It is thus a restoration of ancestry and giving cultural memory back to these works of immense genius and intellect that Oriiz’s The Harbinger set out by refocusing the gaze of the outsider, who lacked the cultural nuance to give context to Africa’s artistic genius. This work echoes loudly one of Chinua Achebe’s famous quotes in his response to Joseph Conrad’s racist novel, Heart of Darkness that discredits Africa and the humanity of its people, when he said, “Africa is not one long night from which Europe woke her up.” Rather, Africa has been one long rhythm of memory that Europe misunderstood and mistook for fragments of genius. Africa’s children therefore owe themselves a historic duty to restore the continent’s battered dignity, a duty Oriiz has admirably undertaken in this work and subsequent ones.

Two radically opposed gazes – one held by western types and the other held by the owners – define the perception issues that dodge art in Africa. The western gaze sees art in African or Nigeria in slices, in fragments and never as a whole, because it lacks the cultural nuance to understand the context in which art in Africa was made. With African objects removed from their different cultural locales on account of colonial conquest, this jaundiced view is understandable. But when it comes from a people who pride themselves on self-appointed mission of civilising others, then it becomes mischievous and intended to score a cultural point of superiority and to undermine the unmistakable genius they strongly want to deny to reaffirm the primitive lie they desperately want to foist on Africa. And as Oriiz puts it, “Africa was not fragmented. It was presented that way. When an object is removed from its cultural and intellectual lineage, intelligence becomes invisible. When lineage is absent, brilliance looks accidental. Fragments create doubt. Continuity reveals design.” The west desperately wants to erase that ‘design’ status in art in Africa, and they succeeded until now.

It is this ‘continuity reveals design’ that becomes the work of the inheritors of this cultural genius others desires so much to deny. The treasures of Africa’s cultural genius were forcibly removed from their ‘lineages’ into foreign places in what results in “When lineage is absent, brilliance looks accidental.” This means that with Africa’s cultural genius removed from its source and scattered all over, it becomes difficult to trace their lineage and ascribe to them their true continuum and value. With their historical continuum truncated, the art becomes accidents of genius rather one long rhythm of lineage brilliance from generation to generation.

But Oriiz’s work helps in the restorative ‘Memory in Motion’ lineage reconstruction from ancient to modern art in Africa and its continuum. And as the author puts it, “Yet memory in African societies was never private. It was civic. Griots were not entertainers; they were archivists. They preserved chronology not with paper but with presence. They ensured memory remained public by keeping it in motion.” This ‘motion’ is the chronological continuum that art in Africa is denied by a western gaze that at once caused the fragmentation and makes it accidental. It’s for their purpose of reducing the lineage of genius in order to deny art in Africa a place in the pantheon of great civilisation.

This is where Oriiz affirms the primacy of his work, when he says, “The Harbinger exists to restore continuity. We do not simplify history; we remove the barriers that made it inaccessible. This publication reveals what should never have been obscured: Art in Africa is not sporadic genius but a continuous intellection tradition.” Oriiz’s restorative work is anchored on its immense implication for the future and why dismantling the impairment of this genius tradition is key to linking the past with the present and the future: “A people cannot move toward the future while being severed from the intelligence that shaped their past. When young Africans cannot locate themselves in their heritage, they inherit doubt instead of evidence. Once continuity is undeniable, History becomes self-knowledge; self-knowledge becomes agency; agency becomes power.”

It is this restoration of self-knowledge, agency and power that propels this work, and as he further amplifies it, “We are not returning to the past; we are returning the past to circulation… The unbroken thread is not about memory; it’s about ownership – the right to speak in our own voice.”

Oriiz constructs the book into three parts. He starts with ‘The Consistency of Form and Philosophical Structure (6000 BCE – 15th Century) from which he treats ‘The Moral Imagination of the Idea of Personhood’ in Nok art and ‘The Aesthetics of Harmony and Civic Authority’ in Ife bronzes. This section deals with the mind and structure that informed these works, which though stand far apart in terms of location have a certain affinity of form and aesthetic unity that are undeniable. Then he moves to ‘Art as State Memory System, Kinship Bond and Infrastructure’ where he also treats art as a memory bank for the ruling system. In this section you find ‘The Benin Kingdom and the Ledger of the Realm’, where art serves numerous functions including being a ledge of state to record its proceedings for future purposes.

Part three is ‘The Horizon of Thought: Modern and Contemporary Practices (Post-1950) with “The Zaria Art Society and ‘Natural Synthesis’”, as its major concern. Of course, the role of the Zaria Art Society is undeniable in its pursuit of an arts aesthetic and vision that are native to the African soil in a return-to-source dynamics that would permeate developments in relinking broken continuum of ancient and modern to contemporary art forms. Of course, this takes the author to ‘Expanding the Toolkit: Post-Independence Practices’ that took root in Zaria but expanded further afield in the long continuum that has sustained art in Africa and Nigeria for centuries.

Part four deals with the ‘Stewardship and the Physics of Memory (The Present Imperative)’ that includes aspects like ‘The Physical Archive Requires Protection through Custody and Conservative Practices’, ‘The Digital Turn and the Circulation of Knowledge’ and ‘Education as Capacity Building’. And as Onuwaje concludes The Harbinger with ‘Movement and Meaning’, he affirms that “The available data support a basic yet firm conclusion that Nigeria maintains an extended dialogue with form, spirit and society, representing one of humanity’s longest creative traditions… The thread continues without interruption because each maker’s rhythm brings forward the future of the past… Our mission is clear: to take the heritage of our collective cultural heritage out of the silence of glass shelves and return it to the pulse of our people… The unbroken thread doesn’t merely endure; it moves. Through rhythm and reason, through art and algorithm, connecting the griot’s voice to the global stage, memory to movement and heritage to horizon and the stillness of library.”

Oriiz U. Onuwaje

The Harbinger, like all other historical art books, is filled with razor-sharp images of artefacts carefully curated for the viewing visual pleasure of the reader. What is more, Onuwaje’s poetic offering in philosophising the visual imageries lends further credence to this work of immense import. For instance, the poetic piece ‘Merchants of Disruption’ comes with an image of an Oba bronze head, and he writes, “They came to plunder -/ objects whose meaning they/ could not comprehend./ Before them stood/ altars and storyboards/ in bronze and ivory,/ but they saw neither order nor beauty/ – only merchandise./ Rifles heavy with the/ trauma of disruption,/ their eyes weighed what/ their minds could not measure/ still, the pulse within endured -/ taken for trade, but/ returned as testimony.vWhile these poetic pieces, which are part of Oriiz’s early morning ‘The unBROKEN Thread’ ritual, greatly enrich and enhance the overall appeal of The Harbinger, Oriiz might do well to pull them into a separate book, as they have the capacity to stand alone as tribute to his lineage restoration genius.

Overall, The Harbinger is a work of a genius. It’s one genius paying homage to forebears who were geniuses and geniuses to whom he would be a forebear in ages to come. It is a work of historical continuum where he stands as the bridge bringing the past to meet the future in the present and making them link hands as lineage and heritage of a glorious tradition truncated at some tragic historical point in the past. Oriiz is the griot, who has risen “again, not with drums alone, but with pixels and code, with rhythm and reels, the poetry of posts and the syncopation of the Afrobeat” armed with “Contemporary technology and cybernetics (as) our new talking drum, through Instagram, TikTok, through every space where stories move faster than sound, we will make memory dance again.” Indeed, Oriiz makes ‘memory dance again’ through “a call across generations to remember, to create, to remix, to reimagine.”