Of women, intentionality, class consciousness in Aj. Dagga Tolar’s ‘being a woman being’

By Bestman Osemudiamen

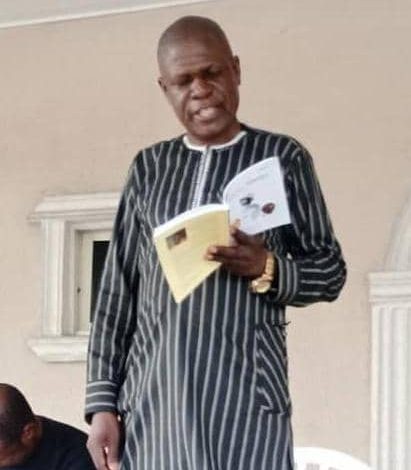

IT all started as a birthday present. I had attended one of Association of Nigerian Authors, Lagos chapter meetings in June— precisely June 11, 2022— a day after my birthday. There, while the discussion on ‘Literature in the Shadow of Politics’ got heated, Aj. Dagga Tolar autographed his latest collection ‘being a woman being’ for me. I was surprised and joyful at the same time. I finally had all three of his poetry collections published this year: Search for the Self, being a woman being, and Nineteen Chapters of the New Name since DisSick Republic came out in 2018.

So far, I read being a woman being for two major reasons: its cover design and the unusualness seem paradoxical of the title. The cover design has some women, both young and old, cover their faces with their hands and in inverted colours— a concept uniquely of the author’s, I believe. It gives an atmosphere of servitude and silence; then, a momentary glance at transgenerational plight— that, all women (the downtrodden at best) suffer. The title, however, is not far from being active in itself— a call to becoming woman (this time, the working class women as most poems suggest): to write and rewrite their history in respect to all spheres of life— particularly gender, sex, and personhood; women are humans, too.

Throughout the collection, Tolar has maintained the use of lower cases except for the word “God” which is, I presume, unintentionally capitalised— an intentionality I find befitting to explain the veil and degrading status, often as social constructs, around being woman. Structured into seven parts: ‘how they define us,’ ‘how they defile us,’ ‘& God is with them against us,’ ‘of sinwoman and saintman,’ ‘this witch of a woman,’ ‘all daughters of eve’ and ‘write back,’ it is clear how Tolar discusses the women question in chronologic thoughts: from points of history, religion, economics, politics, class, and towards the revolutionary.

Entirely, though a poem, there is a narrative blend of feminine first person and a third person omniscient points of view— bringing the plights of women and their struggles closer to the reader.

In part one of the poems ‘how they define us,’ we are met with the subjectivity, submissiveness, and objectification of women as properties, slaves, or commodities. This part sets the pace for the entire collection towards what is to be expected. Though it comprises just six poems, it carries a weight that could make one reminisce on the series of arguments raised by writers such as Simone De Beauvoir’s ‘Second Sex,’ Michael Coogan’s ‘God and Sex,’ Merlin Stone’s ‘when God was a Woman,’ and Christena Cleveland’s ‘God is a Black Woman.’

being a woman being stands out for the creative blend of ideas and form— for a work that seems rather revolutionary than merely critical, one cannot but appreciate the series of reflections, experimentations, and structure that flow in-between poems. For instance, the structure in terms of line-breaks, unusual middle, near, or end rhymes, and the unconventional use of punctuations and grammar add to the aesthetic effect, the subject matter, and should be studied from a point of Tolar’s sense of intentionality. Particularly, these are felt in poems as ‘hell,’ ‘not human,’ ‘I am not me,’ ‘a sour love,’ ‘let him go die,’ ‘seven death seven graves seven times,’ and ‘chifawu spot’ where the first line of the first stanza rhymes with the initial line of the second stanza— a sort of rhyme pattern as ‘abccdd abeeff’ and closer to the five quatrains present in ‘let him go and die’ as ‘abba(s) ccdd eeff gghh iibj.’

Yet it would be an error to wholly centre Tolar’s work on metrical structures or on the musicality in his choice of words. This could be a part, no doubt. But Dagga’s works from DisSick Republic (2018), Darkwater Drunkards (2007)— just as we see in Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s novels and essays after Weep Not, Child and Rivers Between are relevant from the point of ideas he posits and how he manages to weave, express, and retain them in lines.

Oftentimes, I have argued that Ngugi’s writing in Gikuyi is not simply from a point of cultural nationalism. Rather, it is an attempt to raise class consciousness among the Kenyan people as we see in I Will Marry When I Want, Petals of Blood, etc — on the rottenness of the capitalist and imperialist system. This, as well as other related factors to building consciousness, could be seen in Tolar’s being a woman being.

His simplicity, over-repetition or overused words may be as a result of personal development, his supposed targeted audience, and the possibility that being a woman being may have been a collection that long started from his prime— a nostalgic recurrence of women’s plights.

In ‘a sour love,’ we see these overly compounding in stanza two through four: ‘when I say sourness/ I do not mean tastelessness/ which to you is saltlessness…/ …the sharking bite of loneliness/ …life becomes totally meaningless/ …with which/to wish away that meaninglessness…’

From the above lines, it seems the writer struggles with end rhymes to drive a point. However, I am sure much could have been expected from a poet whose work Daggering Boots had been published in 1993. Yet, this is not or should not be a criteria to judge a literary work. Tolar should not be entirely crucified for this literal redundancy— it may or can be assumed to be a product borne out of intentions as with the syntax of Rupi Kaur, Lang Leav, Ada Limon, Christine Mason Miller, and Marcel Martinet.

Beyond his stylistics, Tolar’s choice of words are literal, raw, and unapologetically expressive in poems such as ‘why they deny a good man a woman,’ which refers to Jesus Christ and how he is an exemplar of how women should be treated; ‘ashewo: the fuck hawker’— where he states: ‘this trade is not love making…/ it is surviving,’ and ‘dump the God,’ where the first and second stanzas say: ‘woman/ they say is an afterthought/ of God/ but is God/ not an afterthought of man/ believingly made.’ Hence, the collection challenges the stereotypical, macho-chauvinistic, and indoctrinated readers or women particularly to rethink, reshape, and rewrite their roles and responsibilities as humans.

From here, one can recount how De Beauvoir in ‘Second Sex’ had challenged the definition of who or what a woman is: ‘woman is the negative, to such a point that any determination is imputed to her as a limitation, without reciprocity.’ With this, one could reflect on how women may have been subverted in all ramification: examine words as ‘his’-story, ‘fe’-male, ‘wo’-man, ‘hu’-man, and so on— a narrative Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s ‘The Visit’ explores.

The roles of women are rather unheard and are oftentimes undermined in human history. Until recently, with class struggles and feminist movements breaking and expanding since the first wave, a woman has always been modelled after patriarchialism as the poems ‘a multiple service renderer,’ ‘being a woman being’ (a poem title written in two parts, a sort of improved version of the former), and ‘I am not me’ suggest. Yet, as indicated in Tolar’s preface, Stone’s ‘When God is a Woman’ is a material that contradicts such demeaning history by providing archaeological evidence that points to a period where society was once matriarchal and matrilineal; or, at a point where ‘God’ was once ‘Goddess’ — as even African traditional or cultural history may suggest.

In ‘multiple service renderer,’ we are met with what a woman is in a patriarchal world: ‘a woman is not a being…/ she is the wood to gather/ the pot of water…/ the dirt… to clean/ the goods…/ the bed to lay to be laid…/ she is the blame of things gone wrong…/ she is sold and bought/ she is a property.’ Besides such dehumanising definitions, a woman’s worth is defined by religion, politics, economics, and a classed/capitalist society — a subject matter raised in poems under part 2 to 5 of the collection.

Importantly, it is the revolutionary tone or class conscious expression felt in being a woman being that takes the work away from the cyclic thematic cliché of ‘body,’ ‘empowerment, and ‘individuality’ to a point of movement, provocation, inclusivity, and class struggles, as seen in ‘literature of creation,’ ‘genesis,’ ‘if eve plucked the fruit,’ ‘we slave to serve two masters,’ ‘simply because they rule,’ ‘men always want to be free from blame,’ ‘testimony of a wayward woman,’ ‘we never pool together,’ ‘dump of God,’ ‘woman we are,’ ‘together in action,’ and ‘wear our mothers’ names’ — a resonance, again, with Adichie’s We should all be Feminist, ‘Dear Ijeaweale or a Feminist Manifesto of Fifteen Suggestions,’ and ‘The Visit’ — except that, in Tolar’s case, these issues are directly linked with the economics, politics, ideas, and system of a ruling class built on exploitation, profiteering, inequality, privatisation, and other cases of neoliberal policies rather than middle class female characters. Hence, Tolar’s ‘woman’ may be metaphorically applied to a country lost and eaten at the same time by the madness and greed of its children: ‘a factory for milling out new babies/ who grow the distance/ to have nothing to do with me.’

Aside gender and sexuality, Tolar touches on the emotional, psychological, and commodified nature of love, and possibly, romance or feelings. In fact, it attests to the hypothesis I have once drawn about how women (not generally or homologous, though) are built into a being of receptivity. That is, society moulds them to only be at the receiving end — say, she values words or ‘sweet talks’ or praises as a base for/to authentic romantic expression; while a man is unnecessarily modelled to be assertive after his male ego and toxicity, even in his expression of love. So, if a girl is not sweet talked into being laid as Tolar raises in poems as ‘a kind of heaven, if only,’ ‘their feelings’ (one of my favourites), ‘just it,’ ‘love is ugly,’ ‘fit for digging,’ ‘demeaning love,’ and ‘distrust love,’ what would be or should have been the basis for romantic expression in heterosexual relationships under a patriarchal nomenclature?

Tolar’s ‘being a woman being’ does not only lament. It addresses, informs, confronts, and raises the hope and being of women. And, even subtly, it touches on contemporary debates on identity as with the right for the LGBTQ+ community to exist in ‘together in action.’ However, like Maya Angelou’s, Tolar’s being a woman being could possibly fit into a semi-autobiographical fiction or memoir about the women, personal or impersonal, surrounding or that have surrounded his life. Poems like ‘the widow’s curse,’ ‘sorrowing woman in black,’ ‘the guide and guard,’ ‘I celebrate your courage,’ ‘mummies to be,’ ‘the power of a woman,’ ‘journey into yesterday,’ ‘moremi,’ ‘iya oshoronga,’ and ‘wear our mothers’ names’ are all girdles.

From here, the uniqueness of every of Tolar’s collections lie in the depth, poetic nature, and guidance of his prefaces where, oftentimes, his ideas, philosophical stance, arguments, and other related factors are further expressed: “the current reality (in reference to the subjects raised) was not ordered by nature. If anything, it was birthed through the violence of suppression and rendering into silence a large percentage of humanity… (Hence, it is), not mainly… a woman versus man but as class against class—working class against ruling class… only through such class conflict can humanity hope to have things done differently.”

* Bestman Michael Osemudiamen, a writer and critic, is a member of Aj. House of Poetry