How they stand: Story of writers after winning Nigeria’s biggest literary prize

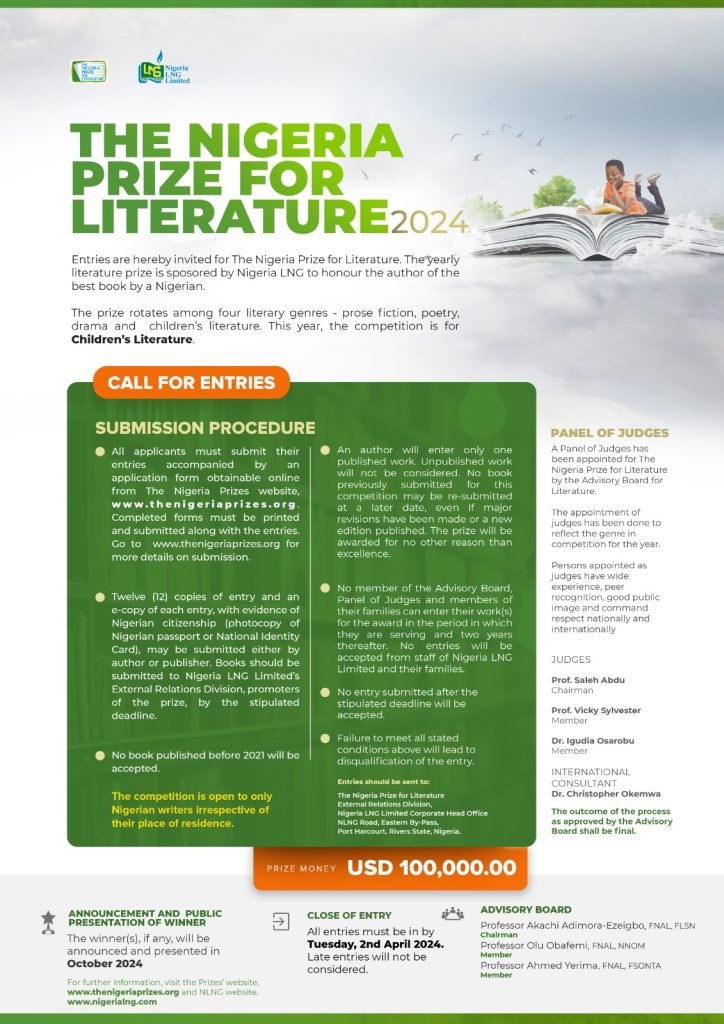

LAST DAY: APRIL 2 SUBMISSION DEADLINE ENDS TODAY!

By Anote Ajeluorou

OF course, there’s no obligation for a writer to continue writing after winning a prize, major or small. But the expectation is that winning a prize should be a motivation to write more, so the win is seen not just a fluke, a flash in the pan, a sudden burst of creativity that soon peters out, but as a ladder to engender if not more wins but more creation. Continuing writing naturally guarantees a writer’s continuing relevance in the creative space. Obviously, the place of champions within the creative space is very fluid; as new champions emerge, old ones that are incapable of renewing themselves with new works fade into the sunset and into oblivion. So in the context of the biggest literary prize on the African continent: The Nigeria Prize for Literature, sponsored by the gas giant, Nigeria Liquified Natural Gas Ltd, how have the ‘old champions’ fared in terms of renewal of their creative spirit? And for those who have seemingly petered out creatively, what memory of them – faint or fresh – is still left in the public imagination?

And as the call for submission of entries for The Nigeria Prize for Literature 2024 ends today, Tuesday, April 2, 2024, it’s interesting to see how past winners stand in their writing careers. This should serve as a wake up call on those who seem to have fallen off their high perch after winning the prize to wake up their muse and get into their writing groove, again!

The first joint winners were Ezenwa Ohaeto (Chants of a Minstrel) and Gabriel Okara (The Dream, His Vision) for poetry (all male) in 2005 while Mabel Segun (Readers’ Theatre: Twelve Plays for Young People) and Akachi Ezeigbo (My Cousin Sammy) also jointly took it for children’s literature (all female) in 2006. Ohaeto and Okara soon joined their ancestors. Understandably, they have been writing among the ancestors ever since. For the women, Segun is old, very old; so not much not much should be expected from her. But Ezeigbo has done a prodigious amount of writing ever since winning it across genres. Her children’s books are over a dozen; in prose she has also done a lot, with Magic Breast Bags perhaps being the most prominent. However, none of these made it to the prize’s longlist before she was appointed chair of the Advisory Board of the prize about six years ago. Ezeigbo is still teaching and writing; in 2022 alone, three offerings came from her: the London edition of A Million Bullets and a Rose (published in Nigeria as Roses and Bullets), Broken Bodies, Damaged Souls and Other Poems and Do Not Burn My Bones and Other Stories.

The next winner was Ahmed Yerima in 2007 with Hard Ground, a play about militancy troubles in the Niger Delta. Though a very prolific historical playwright, Hard Ground seems to be Yerima’s last major outing. Not much has been read from his muse until he was also appointed to the Advisory Board of The Nigeria Prize for Literature.

Kaine Agary, 2008 winner with Yellow Yellow

The following year, Kaine Agary won the prize with her novella Yellow Yellow, also about oil exploration troubles in the Niger Delta that pollute the environment and render the people economically bankrupt while the oil workers and the rest of the country feast fat on that national ‘resource’ that locals see as national ‘curse’. But Agary has since fallen into literary oblivion. She is neither seen in literary circles nor published any book since Yellow Yellow. Is it the case of a writer’s block? How did her creativity fizzle out? Was Yellow Yellow a flash in the pan? When would Agary rouse herself from literary lethargy to create for the reading audience that she’d baited with her first and only work since 2008? It would be such a refreshing spell to read her next work if she manages to tame the muse and bend it to her will…

In 2010 Cemetery Road won the drama prize for Esiaba Irobi, who would receive his diadem posthumously five months after passing away in Germany. But the dead only write among ancestors. Iseee! However, Irobi will still write for the living whenever the volume of his completed works are publish. An Irobi scholar Prof. Isidore Diala, while eulogising him in a tribute in Vanguard newspaper, gives insight into some of Irobi’s unpublished works that amount to a staggering volume.

According to Diala, “At the time of his sudden death, he was also working on the final drafts of many other plays, several of which were in fact already in press: Sycorax (initially titled The Shipwreck, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, commissioned by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival Theater, US), Foreplay (commissioned by the Royal Court Theatre, London, England), What Songs Do Mosquitoes Sing, I Am the Woodpecker that Terrifies the Trees, Zenzenina, The Harp, John Coltraine in Vienna, among many others. Added to his collections of poetry, Cotyledons (l987), Inflorescence (1989), Why I Don’t Like Philip Larkin (2005), the lrobi canon is undoubtedly prodigious.

“Remarkably though, mere prolificity was not the ideal lrobi aspired to: there were many completed scripts he never attempted to produce as there were equally many staged plays he denied publication. His deep passion for pre-eminence led him to approach every creative endeavour as a soul-searching quest for ultimately unattainable perfection, a daring for the elusive ultimate laurel. His life was a fable of the steadfast search for distinction and the self-mortifications that quest often entails.”

For a man who graduated with a First Class for his first degree, Irobi’s massive creative output that outlasts him is not surprising. It’s the hope of Irobi fans that his estate would publish these plays as soon as possible, so they continue to read from the master.

In 2011 for children’s literature, The Missing Clock won it for Mai Nasara (Adeyemi Adeleke), who would ‘japa’ shortly after and hasn’t been heard from ever since. It was his first and only known work. Like his clock, Mai Nasara has since been missing in the writerly circle. Does he still write? What other passion has claimed him from the creative space? We may never know until he crawls out of whatever cocoon he’s been trapped to the abandonment of writing. Only then can his fans be sure whether his was a creative fluke or not.

Chika Unigwe won with On Black Sisters Street in 2012. But she has written an incredible amount of work ever since. In the year she won, she published Night Dancer, Black Messiah in 2014, Better Late Than Never in 2019, and her most recent work, The Middle Daughter last year, 2023. Unigwe also writes in Dutch and has published short stories in that language. Clearly, Unigwe has kept the literary torch burning bright.

Lawyer and poet Tade Ipadeola won the following year, 2013 with The Sahara Testaments. Ipadeola, too, hasn’t published since then. Although he hinted that he was writing a children’s story, but it’s yet to be in the public domain. Or is he suffering the same literary malaise as Agary and Adeleke? Perhaps not, but Ipadeola needs to show admirers of his poetry what he has been up to.

In 2014, Prof. Sam Ukala took the prize with his drama piece, Iredi War. But sadly in 2021, he passed on. There’s no record he published anything before he joined his ancestors. However, his estate has the burden to publish whatever he had written before he joined his ancestors.

In 2016 Abubakar Adam Ibrahim won with Season of Crimson Blossom, the only male writer to have won the prize for prose fiction, the others being female – Agary (2008), Unigwe (2012) and Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia (2021). Ibrahim has published other works sine winning the prize. Dreams and Assorted Nightmares (2020) and When We Were Fireflies (2023) are the most prominent. Ibrahim has also kept the creative flame burning brightly.

Ikeogu Oke’s The Heresiad (2017) would seem to be his second published work after his other popular work Salute Without Guns (2009). He died a year after winning the prize. It’s not known if he left other manuscripts ripe enough for publication.

Also follow the steps of Agary and Adeleke who have seemingly fallen into literary oblivion is Soji Cole, who won the prize with Embers in 2018 for drama. Like Adeleke, shortly after winning the prize , Cole also ‘japa-ed’ and has been teaching in a Canadian university. It can only be expected that he would come out with something good for his fans and students he left behind in Nigeria, and of course for his Canadian students and audience. For now though, Cole’s Embers seems a flash in the pan.

Jude Idade won in 2019 for children’s literature with Boom Boom, and published a new drama piece L’Otor in 2023 that deals with the ‘japa’ syndrome by whatever routes that imperil many unto their death. Idada’s versatility is immense, as he writes across genres and also films that he writes and produces where he has amassed sizeable credits and awards. Clearly, a writer’s block is a foreign concept to Idada, as his muse is ever fertile. Idada is currently on a documentary trail that spans countries across Africa designed to spotlight the ‘dark’ continent to her European denigrators in better light, who never see anything good in her.

Obari Gomba, 2023 winner with Grit

Like lucky first time winners as Agary, Adeleke and Cole, Onyemelujwe-Onuobia was a first-timer and winner of the prize with her prose. Such a remarkable feat for winning with her first work, The Son of the House in 2021. What does she come up with next from her creative arsenal? That’s what literary watchers are waiting to see. Will it be as good as her first? Isn’t that expectation enough to scare a law teacher like her into literary oblivion for fear whatever she writes next will be viewed through the lens of her first work? But a writer’s job is to write well and to damn critics into silence…

Nomad fetched Romeo Oriogun the prize in 2022. A prodigious writer even at his youthful age, Oriogun certainly will keep writing. He was winner of the Brunei Poetry Prize for African writing and has written a lot of chap books. It will be interesting to see what Oriogun comes up with next.

Then comes the university teacher and writer Obari Gomba, who, like Idada, could also be called Mr. Prolific, as he writes across genres, with poetry and drama being his main turf. Gomba is the current champion with Grit. But Gomba has given notice he will turn his attention next to prose fiction where he doesn’t as yet have a book. He’s aiming high in prose and desires to take it to the international level after conquering Africa with The Lilt of the Rebel in 2022 by winning Pan-African Writers Association’s Poetry Prize. His recent offering after winning the prize is a book of engaging essays with a telling title, Free Troubles (2023). He hopes to follow it up with a sequel that will take on the entity called Nigeria in all its ugliness. Obari shows no sign there’s a block a writer has to deal with, as he continues to write.