Deconstructing the mask in Chikwendu Anyanwu’s play, ‘Kingdom of the Mask’

By Chidozie Chukwubuike

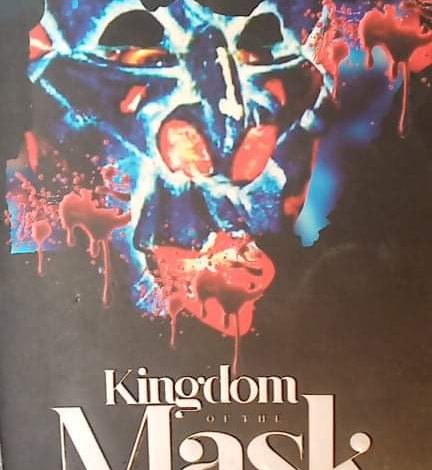

THE graphics design on the cover page of the play, Kingdom of the Mask, is a mask. When you first look at it, you see the image of Africa; then you look again and you see Nigeria traced out in the background. The image drips with blood.

The cover design of a book is the first critical effort at unraveling the signs and significations contained therein. In other words, the reviewer’s job is only a continuation of that exercise already begun by David Opara, a lecturer in the Fine and Applied Arts Department of the Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri. He is the cover designer. We are dealing with Kingdom of the Mask, and here Opara presents us with a specific country and continent in the form of a mask. Is he telling us something that perhaps, at the end of this exercise, we may find out?

The theory of deconstruction as popularized in the humanities presupposes that a text has no fixed meaning and the reader has a major role to play in the production of meaning. Emeka Nwabueze in explaining this theory states thus: “A text contains hidden inscriptions and presuppositions as well as of a multitude of contradictions. Hence, the meaning of a text is always unfolding just ahead of the interpreter.” As the title of this review suggests, we have elected to deconstruct the mask. At face value, the mask is a piece of wood; but on deeper contemplation, other layers of meaning begin to yield themselves to the critic.

The mask in Igbo – African worldview – is highly symbolic; it imbues the wearer with the facelessness associated with spirits. The mask here defines the complex nature of our humanity. Power is a mask. In this country, as elsewhere, a blindfolded woman is used to represent justice because justice is perceived as a mask, faceless. Among ndi Igbo, the throne of a king is a mask; that is why to speak truth to a tyrant king one needs to wear a mask to be at par with the throne. The mask beautifies. The mask also beguiles. It is as shifty as the promises of a politician. Perhaps, all these might have informed the dramatist’s choice of the mask as his guiding metaphor through the plot of his play! Kingdom of the Mask is a creative adaptation of Chinua Achebe’s novel, A Man of the People. As this reviewer seeks to deconstruct the guiding metaphor of the play, so does the play, by extension, seek to deconstruct Achebe’s A Man of the People through a dramatized re-telling that gives it currency.

Just like in the sciences where energy is converted from one form to another, so it is in the arts where a piece of artwork can be converted from one form to another. We have seen sculptures yield to poetry; prose yield to drama and vice versa. Some of the films we see were once pieces of dramatic literature like the one being reviewed here. The enterprise to which Anyanwu deployed his skills is neither easy nor new. In the past, dramatists in different climes have experimented with adaptation; going as far back as the medieval period where Bible stories were adapted as ecclesiastical plays. Most of Shakespeare’s plays were also derived from already existing historical literatures. The prevalence of this phenomenon, in literary history, led to the emergence of a branch of literary criticism Known as ‘Source Criticism’. The fact that a work of art is derived from another does not in any way diminish the individuality, originality or creativity of the latter. It rather enriches the arts firmament. This author is not alone in the lure to ‘de-form’ Achebe’s art, remoulding it from the prose into the dramatic form.

In the 1980s, Things Fall Apart was produced as Television series. Pete Edochie of Nollywood fame came to the limelight through his role as Okonkwo in those productions. In the 1990s, Emeka Nwabueze did a dramatized recreation of Achebe’s novel, Arrow of God. Today, we have another play. Kingdom of the Mask by Anyanwu, which is a dramatic re-imagination of Achebe’s A Man of the People. Borrowing from deconstruction, which, according to Nwabueze, is an accessory to ‘the death of the author,‘ we do not intend to encumber this review with the source literature because the author is no longer the source of meaning in a text; and by extension therefore, the source literature cannot be the source of meaning in the criticism of any work of adaptation; the death of the author hence includes the death of the source literature.

Adopting historification, an age-long African performance technique popularized in the West by Bertolt Brecht, as his writer’s concept, Anyanwu gives Odili – the Protagonist – a dual role as both Narrator and the Main Character. The play begins very close to its end – at the hospital. In a state of delirium, Odili starts his narration and the reader is transported, through the dramatic technique known as flashback, to the beginning of the story.

The people of Anata community hold a civic reception in honour of their illustrious son- Chief the Honourable M. A. Nanga, MP. It is at the Anata Grammar School where Odili works as a teacher. Odili’s father, Mr Samalu, who is the Ward Chairman of Chief Nanga’s Political Party (POP), is the anchor of the reception. He introduces Odili, his son, to Chief Nanga who remembers teaching him in Elementary 3 before joining politics. Now Odili is a University graduate and Chief Nanga, in excitement, invites him to Lagos to help him sort out his scholarship needs. The Lagos visit, however, turns out a disaster; Chief Nanga snatches Odili’s girlfriend, Elsie, from him. Odili leaves his house embittered and vows to take revenge.

While still in Lagos, Odili joins camp with Max (an old friend) and his group to form CPC, a new political party. Odili sees this as an opportunity to get back at Chief Nanga for snatching his girlfriend. Odili, afterwards, returns to Anata and begins his political activism. He holds a political rally in his village Urua, in spite of Chief Nanga’s peace overtures. His family, and even the entire Urua community, are later to be victimized for his ‘impudence’; his father loses his position as the Ward Chairman of the ruling party, arbitrary fines are imposed on his family for hosting illegal rally in their compound, the water pipes in Urua community are removed.

Odili is mobbed at Chief Nanga’s political rally at Anata. He is still hospitalized at the time the election takes place. Max is assassinated by Chief Koko’s thugs (Chief Koko is Chief Nanga’s friend and colleague at the parliament). In retaliation, Eunice (Max’s fiancée) guns down Chief Koko and surrenders herself to the police. The post-election violence that ensues leads to a military coup that leads to the arrest of Chief Nanga and other corrupt politicians. In a dramatic twist of fate, Odili, whose girlfriend Chief Nanga snatched in Lagos, ends up with Chief Nanga’s second wife at the end of the play.

The symbolism of the play opening in a hospital ward should not be lost on the reader. The hospital is a place for the sick and infirm. In this particular hospital ward, the entire society is represented by the diversity of the characters. Mr. Samalu, Odili’s father, is an old politician, and therefore represents the old political class. The Doctor represents the aloof Professionals who think the political problems of the country do not concern them. The Nurse represents the subservient and equally aloof women-folk. The two police officers represent the law and the impunity they represent in our society. Edna is a College Lady, and so can be said to represent the youths. Finally, Odili is the radical intellectual idealist who thinks that by mere youthful exuberance the world can be changed. The subject matter of the play is politics in post-colonial Nigeria; emanating from that subject matter are themes of corruption, betrayal, violence, hypocrisy, misplaced priorities, the morality question, love, marriage, loyalty, fear, vengeance, infidelity, political brigandage, sex, human rights violations and ignorance. The striking and sad observation here is that these problems highlighted as themes in this play are still prevalent in today’s Nigeria, and Africa at large.

The ironic revelation in the play is that in Corruption the old and the new become so unrecognizably the same that one cannot be differentiated from the other. Also in corruption, the political class and the masses are united. This observation can be seen in the exchange between Max and the Ex-policeman during the rally at Odili’s father’s compound:

Max: … you must not give your votes to men who have just one thing in mind- to eat and forget the people.

Ex-policeman: (Raises his hand and is allowed to speak) We know they are eating, but we are eating too…

Again, Mr. Samalu tells his son, Odili, “Politics is what you get out of it.” The total lack of moral persuasion in the Nigerian society is captured in the play when the same society that ostracized Josiah, the shopkeeper, for trying to steal the blind man’s walking stick for the purpose of money ritual is seen fraternizing with the same Josiah who is now in the political good books of Chief Nanga. In one breath, they call Josiah a criminal and accuse him of having ‘taken so much for the blind to see’ and in another breath, they hail and chant Chief Nanga’s praises for beating Odili who tries to expose Nanga’s deception and lies. These inconsistencies in the character and nature of man as depicted by the characters in the play under review make the choice of the mask as the guiding metaphor very apt.

In Act 3 Scene 3, after the election has been won and lost, Odili’s kinsmen at a playground in their village, Urua, are seen trivializing the fact that the destiny of an entire nation has once again been mortgaged till another political season. They chant: We have recycled ebebe-ebebe.

And they actually go ahead to brag about their being a nation of ‘recyclers’; that no one who drinks the old wine wants the new one, because old wine is good and well fermented. And they make mockery of their kinsman for daring to challenge the status quo, saying, “The toddler that wears the father’s cloak will have the cloak blindfold him”. The docility of the masses towards the impunity of the political class is aptly captured on page 121 where the villagers justify the corruption of the political class by comparing it with that of the colonial administration, saying if they did not die from the white man’s looting, they would still survive the current looting. This is a defeatist mindset.

The artistic employment of such extra dramatic devices as mime, dance, stylized pantomimic movements and masking give fillip to the play.

The playwright uses subtle fore-shadowing at different times to prepare the reader for the bandwagon mentality that is the bane of the present society. However, the playwright’s experiment with the narrative technique does not appear to have come out very effectively. Odili’s transition from Narrator to the Main Character, and vice versa, is poorly realized. The last statement in the text by Odili on hearing that the military have taken over government is quite troubling and should be taken as a warning against heating up the system.

Perhaps, the final act of the mask Dancers, placing their masks down on the front stage appears to convey a little ray of hope that a new beginning is possible.

A critical reader would observe that out of all the major characters in the play, there are two that are hardly tainted by either corruption or moral burden. The two characters are: Edna and Eunice. Both characters are women of very strong moral convictions. Edna is Chief Nanga’s proposed second wife and Eunice is Max’s fiancée. They both made tough choices when they could simply have taken the easy paths. Edna rejects the glitz and glamour of life with the Minister, while Eunice would not mind going to jail just to remain on the path of honour. Their male counterparts have all been found wanting in honour’s score-card. Does this suggest a deliberate effort by the playwright to redirect society to the under-tapped potentialities of the womenfolk?

The creative writer has repeatedly been described as a prophet. In 1966, Achebe published A Man of the People which so vividly predicted the tumultuous political events of the time that the military tried to apprehend him. In his last book, There Was A Country, Achebe explained what happened then thus:

“Some may wonder why soldiers would be after me so fervently. As I mentioned, it happened that I had just written A Man of the People, which forecast a military coup that overthrows a corrupt civilian government. Clearly, a case of fact imitating fiction and nothing else, but some military leaders believed that I must have had something to do with the coup and wanted to bring me in for questioning.”

It is only fools that allow an ugly history to repeat itself. There was a certain bird that cried at night in 1965, and the following morning someone died. In 2022, it appears that same bird has begun to cry again. Anyanwu, as a creative writer committed to his calling, has called the society’s attention to the cry of that ugly bird of bad omen. Through Kingdom of the Mask, the playwright has succeeded in exposing some of the ugly political tendencies that played out and subsequently led to the fall of the first republic.

The publication of this book in 2022 is symbolic. Few weeks from now, Nigeria will be going to the polls to elect their new leaders. The atmosphere is tense, but thanks to Anyanwu’s timely offering- any reader of this play must, no doubt, be the wiser. It is recommended to ‘We’ – the masses, who have no head; to ‘They’ – the leaders, who have no heart; and to the youths of our dear country who have lost the balls to stand for what is right and just. The play Kingdom of the Mask is capable of dispelling the gathering clouds of political violence. Anyanwu has played his part… Write; it is left for Nigerians to play theirs… Read!