Writers reflecting on their roles in times of crisis at a panel session

By Fodio Ahmed

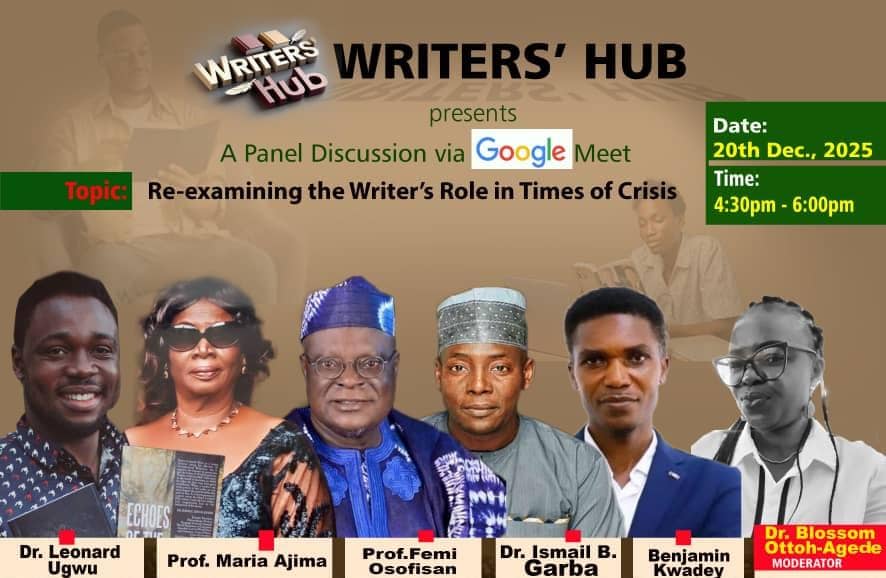

WRITERS‘ Hub held the eighth edition of its monthly panel discussion on December 20, 2025, via Google Meet. Themed ‘Re-examining the Writer’s Role in Times of Crisis’, the session brought together esteemed panelists to examine the layered responsibilities of writers in times of crisis.

The discussion was moderated by a distinguished scholar in Stylistics, Media Rhetoric, and Peace Linguistics, Dr. Blossom Ottoh-Agede. She’s the author of the double TETFund award-winning book, Style and Media Rhetoric: Reporting Terrorism in Nigeria, and has published extensively, including poems on patriarchal resistance and injustice. She’s also the editor of the Lines, and coordinator of the Creative Writers’ Club, Federal University, Lafia (FULafia).

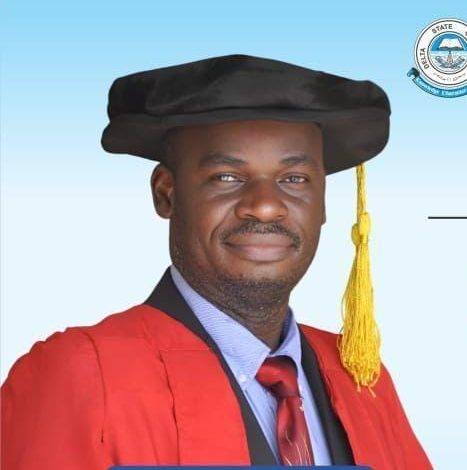

The event featured distinguished personalities, including Professor Emeritus Femi Osofisan, a celebrated Nigerian playwright, critic, and scholar who reshaped modern African theatre with over 60 plays and works in other genres. Benjamin Kwadey, a Ghanaian veteran filmmaker and actor with over 30 years of experience in entertainment, skilled in content creation and artistic coordination, was also part of the discussion. Dr. Ismail Bala Garba, an accomplished bilingual poet with works published in the UK, US, Canada, and more, and author of Line of Sight (2020) and Ivory Night (2024), also shared his insights. Professor Maria Ajima, a renowned professor of African Literature, with 60 poetry collections and multiple awards, was part of the discussants. There was also Dr. Leonard Ifeanyi Ugwu, Jr., a fellow of Ebedi International Writers’ Residency, with a debut play Babel and Boys (2023) and acclaimed poetry collections.

Osofisan set the tone by drawing a crucial line between writers as citizens and writers as artists. As citizens, writers grapple with shock, pain, and anguish just like everyone else caught in crisis. But as artists, they’re called to do more – to refract raw experience through the prism of their work, helping societies make sense of turmoil and find pathways through it.

“Art is a balm for history’s wounds,” he said, “a way to overcome and heal,” noting writers can illuminate dark corners, spark dialogue, and maybe even catalyze transformation by distilling chaos into narratives. In this light, writing in crisis isn’t just about bearing witness; it’s about transmuting pain into something that aids collective healing. The artist’s task is to capture the rawness of experience and transmute it into understanding.

Ajima emphasized the significance of futuristic writings that project desired societies and imaging tomorrow through the lens of past and present. She urged African writers to craft futuristic works like George Orwell’s 1984 to help liberate the continent from technological underdevelopment and envision empowered tomorrows.

In her words, “Writers should engage in futuristic writings to project what they want their societies to look like in future, or conjecture on what they think tomorrow will be, based on what happened in the past, and what is happening in the present.”

Defining crisis as a time of intense difficulty or danger, she stressed that writers must walk a tightrope, addressing urgent issues without exploiting trauma for sensational effect. To strike this balance, writers can clothe traumatic realities in artistic language, leveraging empathy and rigorous research.

“Dress traumatic realities in an aesthetic manner,” Professor Ajima said, “using figurative devices and euphemistic language to make writings palatable yet impactful.” Citing writers like Nawal El Saadawi, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and Wole Soyinka as embodiment of perseverance in adversity, she advised writers to always aim at the truth, pose questions from multiple angles to probe the layers of a crisis.

Garba unpacked the evolving role of writers in the era of misinformation and disinformation, especially on social media where speed often triumphs over accuracy, saying, “Writers are no longer just storytellers. We’re custodians of truth, interpreters of chaos, and a moral check on the virality that spreads falsehoods.”

To navigate this landscape, writers must consciously resist sensationalism, ground their work in thorough research and context, and engage readers with critical empathy. According to him, to counter false narratives, writers can employ several strategies: Rigorous fact-checking and transparency about sources help build trust. Placing information in historical, cultural, or political context adds depth and understanding. Reframing narratives to reflect complexity and lived experience can counter simplistic falsehoods. Exercising restraint to avoid amplifying unverified claims is also crucial. Dr. Garba added that crisis reshapes the writing process itself by disrupting focus, heightening emotions, and redefining purpose.

“Writers need to adapt by accepting fragmentation as a valid form of expression, slowing down to process emotions and implications, and cultivating patience, humility, and awareness of their limits. In crisis, writing shifts from mastery of craft to attentiveness to reality, language, and the spaces between words. It’s about listening as much as speaking, and using words not to dominate but to illuminate.”

Kwadey underscored the significant influence writers wield in shaping public discourse and informing policy decisions, stressing that responsible storytelling is paramount.

“As writers, we’re bridges between communities and those in power,” he said. “Our words carry weight, so we must craft narratives with accountability and a keen sense of impact.”

Ugwu Jr., building on the previous contributions, highlighted the importance of tapping into themes that genuinely resonate with people’s experiences and struggles. He asserts that writers have a dual responsibility: to amplify voices often left unheard, and to navigate sensitive topics like trauma with an abundance of care.

“Trauma themes are a double-edged sword,” he cautioned. “We must stay attuned to critical issues and craft stories that ignite thoughtful dialogue rather than inflict further harm.”

US-based Nigerian author and President of Literary Authors Cooperative, Mrs. Awele Ilusanmi, was among the participants who contributed to the discussion. She highlighted the often overlooked writers’ personal crises.

“Let’s not forget that writers themselves can be in crisis,” she said. “What safety nets can we create to support creative regeneration? For writers to stay relevant to themselves, their communities, and their nations, author insurance and self-care are key. This means prioritizing mental health, building supportive networks, and maybe even rethinking how we define productivity in times of turmoil.”

Those who participated in the panel discussion included Prof. Dul Johnson, Dr. Lizi Ben-Iheanacho, Prof. Victor Dugga, Mallam Denja Abdullahi, Mr. Kabura Zakama, Salamatu Sule, Mallam Ahmed Ikaka, and others too numerous to mention.

The Writers’ Hub December session stressed the significance of responsible writing in times of crisis, shedding light on strategies for writers to navigate intricate challenges and make meaningful contributions to public discourse. As writers adjust their approach, they must focus on being attentive to reality, language, and their own limits, ensuring their works foster understanding, healing, and positive transformation. This recalibration involves embracing empathy, rigorous research, and thoughtful storytelling to address pressing issues without exploiting trauma. Writers can amplify marginalized voices, combat misinformation, and help societies process and overcome crises through this careful approach.

Ahmed, the rapporteur to the discourse, is a Minna-based writer and journalist