USD$100,000 prize money: Man battles two women for biggest literary pay cheque

By Anote Ajeluorou

IN what appears like a repeat of The Nigeria Prize for Literature 2021 edition, a male writer is battling two women for the biggest literary prize on the continent worth USD$100,000, sponsored by gas company, NLNG. In 2021 two female writers Abi Dare and Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia had a showdown with Obinna Udenwe for the literary prize. Also like 2021, the category was prose fiction as well. Dare’s The Girl with Louding Voice and Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s The Son of the House wrestled with Udenwe’s Colours of Hatred. In the end, it was Onyemelukwe-Onuobia’s The Son of the House that took the literary diadem. However, while Udenwe and Onyemelukwe-Onuobia were and have remained home-based writers, Dare was and is still based abroad. However, this year that configuration is reversed with all three contending writers based abroad.

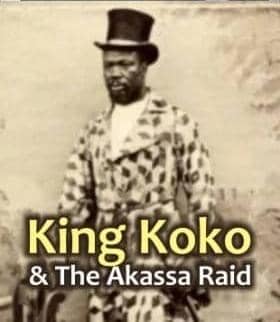

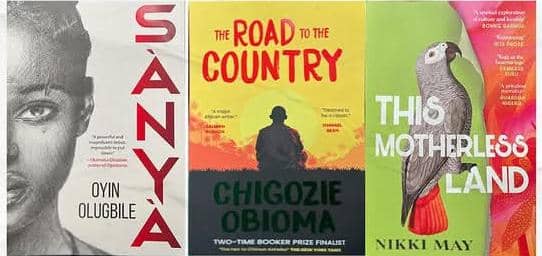

Chigozie Obioma is the sole male writer battling it out with Nikky May and Oyin Olugbile for the 2025 literary diadem this year. Obioma’s The Road to the Country is in contention with May’s This Motherless Land and Olugbile’s Sanya for the October 10 prize award ceremony in Lagos. With there then be a repeat of 2021 with a female writer taking the prize home or perhaps that there will be a reversal of fortune with a male writer smiling home, or perhaps the unlikely event of a joint winner? These are some of the questions on the minds of many as Nigeria’s literary community waits with baited breath for the announcement of the winning book in a few weeks’ time.

What exactly did the three writers say about themselves and their books – The Road to the Country, Sanya and This Motherless Land? Below is a revisit of the reflections on August 3 at the CORA-NLNG Book Party where the three writers had audience with Nigeria’s culture community and spoke about their works and their motivations.

For Olugbile, the author of Sanya, her journey to writing the novel began unexpectedly, as it took root from her university days. “I studied Theatre Arts at the University of Lagos and, sorry to say, all through my four years, I hated being in class,” she admitted. “I was one of those children who wanted to study something else. I ended up in theatre arts because my dad said, ‘Listen, you can’t miss this year’s admission. Just get into school.’ I wanted to be a lawyer.”

Oyin Olugbile (left); Chigozie Obioma and Nikky May

Despite her lack of interest in theatre as course of study at the time, she said the lessons stayed with her. “We studied very interesting topics, from mythological gods and all of that, but I never thought they would matter to me later,” she said. After graduating, she immediately enrolled at Lagos Business School and embarked on a career as a consultant in social impact, leaving theatre arts far behind. But that changed in 2016 while she was doing research for a not-for-profit organisation focused on education.

“Midway in the research, I stumbled upon the story of Sango again, and I think I had that residual memory from school,” Olugbile said. “While doing proper index research, I realised a lot of things did not add up. In Africa, the way we tell our stories is usually through folklores, and sometimes even the childish whispers that someone told someone else until it becomes a different kind of story. The character of Sango, for me, didn’t just add up. Somewhere, I think, he has been misrepresented, and I felt I had a different version of how it could have been told. I told my husband, ‘I think I’m going to write it.’”

Olugbile began writing in 2016–2017, completed the work in 2020, and saw it published in 2022, after five to six years of in-depth research into African mythology and storytelling. She said preserving these traditions was central to her motivation, adding, “It is necessary to tell African mythology and African stories for the sake of future generations. I live here in the UK, and I’ve lived in the United States, with children who don’t even understand or have knowledge of our rich African culture. I believe that for us to keep it for the future, we must pass it on through African storytelling — to give them hope that there is a possibility things can be preserved in Africa beyond people just looking for money. Storytelling is that legacy we can pass on to the generation here now and the one to come.”

Although unplanned, Obioma said The Road to the Country is a deliberate filling of gaps within African literature, as he said, “I’ve always joked that I do the dirty job of African literature. By serendipity, I find myself doing stuff that has not been really done, at least to my knowledge.”

He explained that this impulse shaped his second novel, which he embarked on because he saw a glaring absence. “There was no cosmological novel in the likes of Milton’s Paradise Lost or Dante’s Inferno, and I thought, we have all these cosmologies, so why don’t we write something like that? I did it with the Igbo cosmology” in An Orchestra of Minorities.

With The Road to the Country, Obioma turned his attention to the Nigerian Civil War, a subject he said is deeply personal to him, adding, “I wanted to write about Biafra because I lost a lot of relatives in that war. It was very brutal. My immediate mum’s older brother, for instance, was killed, I think in the first two weeks of the war, and he was only 19.”

However, Obioma said his research revealed a surprising literary pattern, when he said, “I found that all the books that have been written about the war are mostly what I’d call wartime fiction — where the battles and the war itself are in the background, rather than foregrounded as the main focus. There is no war novel I can think of that really captures it in the way All Quiet on the Western Front or 1917 does. The closest is Sozaboy by Ken Saro-Wiwa, which I think in my estimation is about 40–50% war novel. So I decided to write one.”

For Obioma, the task was both demanding and necessary. “It was not an easy task, but I thought it was important to document some of the battles. Everything in the book is real — it actually did happen. The Biafran war against Nigeria was one of the major conflicts of the 20th century, and I think it deserves to have its own war fiction.”

May, the author of This Motherless Land, who has set for herself the task of unravelling the cosmopolitan difference and similarities between Lagos and London, on the one hand, and her dual heritage of Britain and Nigeria (Wahala being her first novel), describes her latest work as her most personal yet, drawing deeply from her own experiences growing up in Lagos in the late 1970s. Through her protagonist, Funke, May revisits a world that mirrors her own childhood—living at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital with her doctor father and teacher mother, spending weekends at the beach in Takwa Bay collecting cuttlefish shells, and navigating the cultural and social nuances of her dual heritage.

Although fictional, the novel This Motherless Land is steeped in autobiographical detail, allowing May to explore identity, belonging, class, and culture, while also confronting the prejudice and privilege encountered in both Nigeria and Britain. “I’m half Nigerian and half British, but I’m also fully Nigerian and fully British,” she says, underscoring the complexity of her cultural perspective and identity. In crafting Funke’s journey, May introduces challenges and tragedies—most notably the early death of the character’s mother—to deepen the exploration of these themes.

The writing process became both a satirical critique and a cathartic exercise. By poking fun at the absurdities of prejudice and societal expectations, May injects humour and sharp observation into the narrative. “Writing is better than therapy, and certainly cheaper,” she quips, noting that the project became an almost nostalgic return to her own youth and her time in medical school in Lagos. For May, This Motherless Land is more than fiction—it is a literary bridge between two worlds, and an intimate chronicle of the life she was, in her words, “born to write.”

Who goes home with the USD$100,000 literary prize money? October 10, 2025 is a date with literary destiny, no doubt!