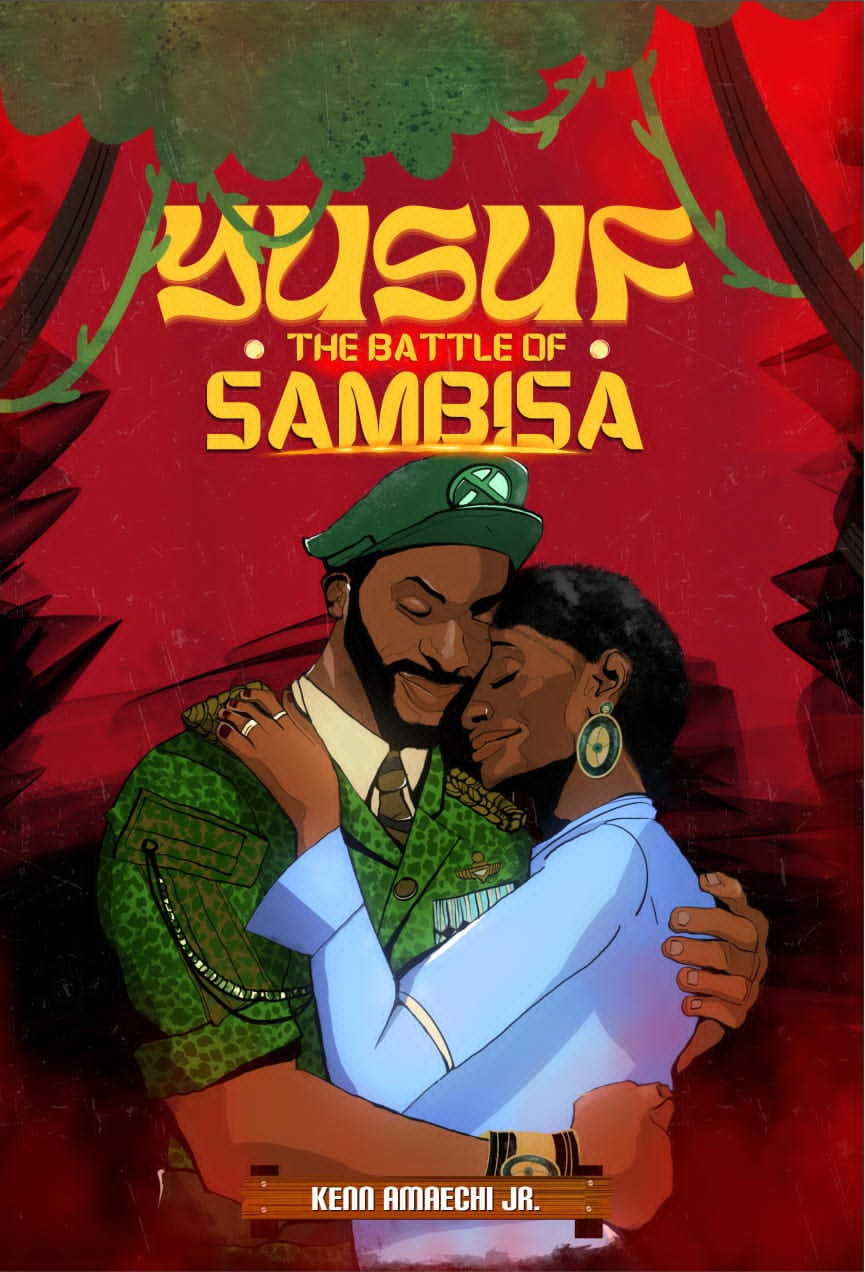

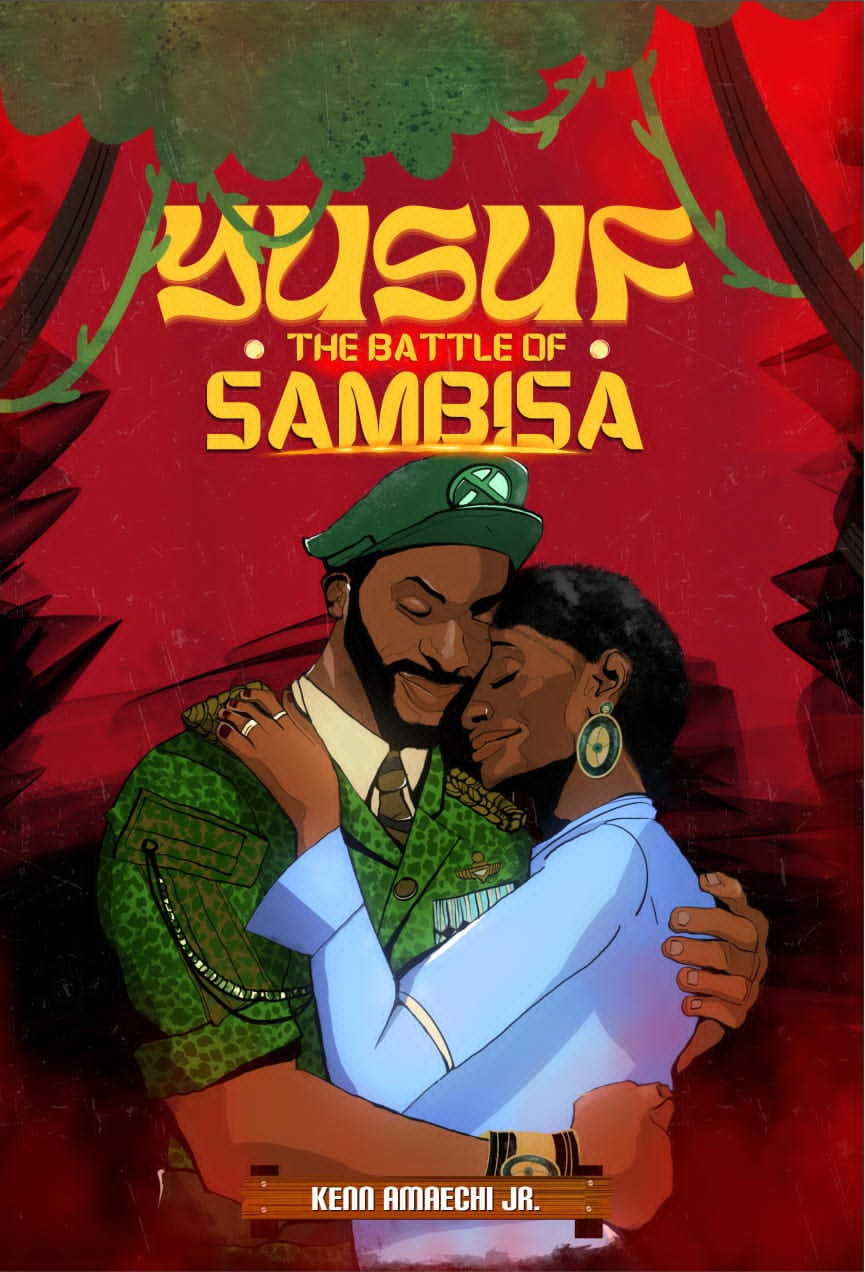

The novelist is still a teacher: Reading Kenn Amaechi Jr.’s ‘Yusuf: The Battle of Sambisa’

By Oko Owoicho

YUSUF: The Battle of Sambisa by Kenn Amaechi Jr. contributes to one side of the conversation on Nigerian literature—the novel adds to the perspective that holds the notion that contemporary Nigerian literature still adheres to the traditional scheme laid out by the first generation of writers, who believed that art is supposed to serve as an agent of social change. This notion is made popular by Chinua Achebe’s essay “The Novelist as a Teacher,” published in Hopes and Impediments. The novel, following the critical realist tradition that pervades most popular literature, takes us through Nigeria’s history and current events.

The novel offers us a bildungsroman of Yusuf’s growth and journey. From the University of Maiduguri, we encounter his progress, witnessing his days of innocence and youthful naivety with Maryam. The vivid description of their innocence; how in the heat of passion, two young lovers explored the desire of the human body, and at this point, the reader slips into reminiscence of his/her first kiss, that phase in one’s life that we are not encumbered by the duties and burden of existence. Through this, we follow as he ends the NYSC scheme, he confronts the crucial subject of survival, and that is where his Uncle’s advice comes in. To join the Nigerian army, we learn from Uncle Bala that if he converts to Islam, it would be a lot easier, and this offers the space for the novel’s discussion of the subject of religion in Nigeria.

Through laying the foundation to make his point known to Yusuf, Uncle Bala recounts his own journey and conversion from Christianity to Islam. We learn how, in the face of stark poverty, his ailing mother in the hospital, and younger brothers struggling to graduate, he is confronted with accepting the offer of conversion to enhance getting the slot for a direct entry into the Nigerian Army. He says that, “I became a Muslim when I faced something similar to your present situation. You know, we are minorities where we came from, and because of that, we face discrimination. You suffer this kind of discrimination because you are a minority tribe, because you are a Christian, because you are a northerner who bears an English name, and because you choose to be different.”

The reality of this theme offers us a Marxian look at the subject central to many Nigerian novels, and that is the dialectics of survival, and in this context, the plight of the minority tribes in Northern Nigeria. Uncle Bala tells Yusuf that being from a minority ethnic group and being from a Christian minority means being faced with dual limitations in one’s survival. Hence, he implores Yusuf that “you may want to take my approach. You won’t be losing your soul, but you will gain it more, for you will come to appreciate God better.”

Amaechi raises a core concern on the subject of being a Nigerian and the question of survival. Life in Nigeria, despite the pretence of ethnic and religious loyalty, cannot be exempted from the main subjectivity of the human quest for survival. The dilemma we face, the choices we make are firstly dictated by the need to survive as humans, and Uncle Bala’s life exemplifies this. But—and this is why sometimes I am opposed to Marxist subjectivity—while the survival ethos influences Yusuf’s decision, just like his Uncle, there is the emotional implication of conflicts that arise in his dealings with his family. This conflict begins to manifest when he goes home for Christmas and hopes to share the news of his conversion with his family. So “Yusuf noticed his mum’s unhappiness about his lack of enthusiasm to go to the church and celebrate his homecoming. He, too, became a bit depressed because it was only one thing, his conversion to Islam, that stopped him from going to church”. Hence, we witness the shift from that period of innocence to the period that our survival instincts drive choices, and these choices are layered because they also involve the emotional well-being of the people in our lives.

However, while Yusuf deals with this personal issue, there is also the national problem of insurgency. We are ushered into this plot sequence when he is deployed to the Engineer Search and Disposal Regiment Unit for training in bomb disposal. Dr. Nafeez Rafsanjani hands Yusuf and his colleague a sheet which contains the foundation and the mayhem the Boko Haram sect has unleashed on the country. Then, through flashback, Yusuf recounts his own experience in Maiduguri, the period before he got admission into the university, “Listening to the lecturers recount the history of Boko Haram and the atrocities they had committed reminded Yusuf of his life experience in the Maiduguri metropolitan”. Through this technique, we encounter how the insurgents targeted the Igbo and Christian-dominated areas at the initial point. Our emotions are stirred as we encounter the story of Chief Ikenna Onukwe’s death. Chief “was reputed to be a very peaceful and easy-going fellow and had lived in Maiduguri Town for over 50 years, having done his apprenticeship before he started his own business and became a millionaire supplying goods to the neighbouring countries of Chad and Cameroon”. The impact of this was that people, who like Chief, lived in Maiduguri for almost all their lives, had to start looking for means to move back to the East.

Through Yusuf’s flashback, he also recalls his friend’s experience of the death of his brother. The friend’s brother, Gaius, ran into the terrorists, and they were sifting those who were Muslims from the Christians. Gaius knelt and pleaded “with the terrorist to please spear his life as his parents depended on him for their survival; that he even pleaded to be given another chance so he could practise Islam; but all these fell on deaf ears as the young, fierce-looking terrorist shouted Allahu Akbar and shot him at close range on his face and his chest, and he died instantly despite denying his own God”. This touching part of the story affirms Raymond A. Mar et al.’s observation that “Emotions are central to the experience of literary narrative fiction.” This killing of Christians does not mean Muslims were spared. The author informs us that: “Even though the terrorists have always preferred to target Christians, they have not ignored moderate Muslim clerics… In the same vein, they bombed mosques and destroyed Islamic monuments and institutions that they considered to work against their objectives”. Yusuf’s encounter with the reality of the insurgent hits him when he is deployed to Sambisa Forest. We share in his dread when the Commanding Officer tells him, “On your marks, set, and get ready. Boko Haram is coming. I’m sure your unit commander will brief you soon.” He laughed when he said this, but Yusuf never caught that smirk and concocted laughter”. Not long after, he encounters the battle that almost claimed his life and, eventually, his capture.

As we move through the grim story of the killings, the different angles through which the acts by the insurgents and the contradiction in their actions also yield themselves. Amaechi runs this broader angle through conversations related to the protagonist and conversations that he encountered. There is the ethnic angle as seen through the death of Chief and others, and how this reminds Yusuf of the incident during the Nigerian civil war. This is also, importantly, the outsider angle. The negotiator for the exchange between the government and the insurgents, Alex, becomes a crucial voice offering reasons for the absurdity of the Boko Haram menace in Nigeria. For:

He had been wondering that, if the terrorists, as they claimed, hated white people and were opposed to modern education and ways of life, why had the Imam chosen to deal with Alex, who was a white British man and could be easily assumed to be a Christian? Why did they also use Western-manufactured arms and ammunition? Why not use only their stones, bows, and arrows to fight? Why use a mobile phone – a creation of the West? Why use a radio and consume alcohol, cigarettes, and weed?

This contradiction reflects not only Alex’s thought, but also the question that even Nigerians have been asking. Furthermore, Alex questions the rationality of the government negotiating with the insurgents, “You cannot stop terror by appeasement; you can only fight terror with terror. And these people certainly do not have the ability to discern between right and wrong, something that Alex believed every human being, including atheists, should have, irrespective of their beliefs.”

Using the perspectives of different characters, Amaechi replays the role of the novelist as teacher, to remind us that humanity’s quest for survival is central to existence, and most of the choices we make are backed by our quest for survival as humans. The novel, following the audacious move of Achebe’s A Man of the People, ends by foreseeing a military coup happening in Nigeria. If the novelist were to shift from being only a teacher to a seer, we cannot tell. But Amaechi follows the tradition of Nigerian literary project by offering a stark realism which reflects contemporary Nigerian existence. Save for the commentaries, which almost affected the aesthetic and plot of the novel, Amaechi’s Yusuf: The Battle of Sambisa is a literary documentation of contemporary Nigeria.

* Owoicho, a critic and award-winning poet, is the founder of Benue Poetry Troupe and Team Lead for Afrika-Writes