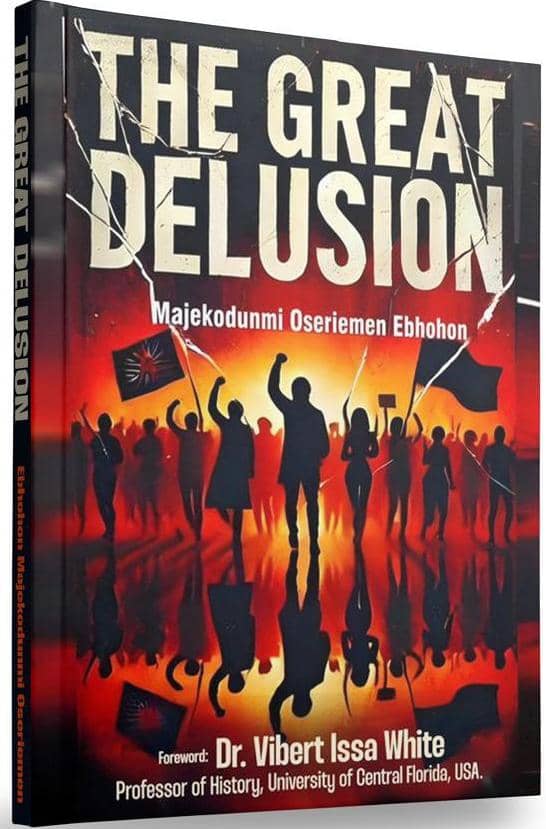

Ebhohon’s ‘The Great Delusion’ as grand dramatic enactment of African-Americans’ historic contribution, identity

By Godini G. Darah

THE Great Delusion by Majekodunmi Oseriemen Ebhohon is a grand dramatic enactment of the saga of African Americans to restore their historic contribution and identity in a race-torn society. They are victims of exploitation and oppression engendered by the experience of slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Ebhohon explores the resourcefulness and resolute spirit of the Black victims of racism to challenge their oppressors. The Black Community rises in unison to overturn the system of the White supremacists who deny the Blacks of their worthy contribution to the development and sustenance of the affluent society. The Black Community emigrates from the unjust society, leading to confusion, chaos, and collapse.

Applying the dialectical method of storytelling, Ebhohon uncovers the stolen knowledge and legacy of the dispossessed Blacks. Through a clash of contradictions, the oppressed and marginalized are provoked to leave the community and return to their ancient African homeland. Their departure results in the dislocation and disruption of the social and economic order that defines the affluent society. This aspect of the play examines the theme of racial equality and justice.

The structure of the play is organised to achieve the overall goal of exposing the delusion of the oppressive white ruling class. There are three acts divided into eleven scenes. The actions of the play evolve chronologically to realize the thematic objective. The first parts dramatise the plight of the marginalized blacks and how they strive to transform their existential condition to emancipate themselves and assert their identity. The event of the festival depicts the advantage of self-reliance and community bonding. The White rulers interrupt the festival programme and compel the Black Community to resist the erasure of their tradition and racial pride. The ultimate outcome of this clash leads to the point of the Black Exodus, an action that underscores their capacity to act in concert. The catastrophic consequences of the exodus of the Black Community make the racial supremacists recognize their weakness; they had never acknowledged that black labour and ingenuity constituted the bulwark of their society’s strength and prosperity. Mr. Deep, the major racial supremacist, suffers a personal tragedy as his son, Jack, dies as a result of the failure of medical and social services.

There is an ironic twist in the tale. Deep’s wife, Margaret, represents the opposite side of the racial divide. She subscribes to the principle of justice and racial equity. She recognizes the Black Community as partners, not as inferiors. Her son, Jack, is a friend and colleague of Kwame, a black boy. Their relationship promises to bridge the racial gulf. When Jack needs an emergency surgery, white doctors do not rise up to the emergency occasion. But it is a black surgeon, Dr. Mensah, who takes the risk to carry out the operation. In spite of these revelations, Mr. Deep does not support the black-white accord. He is blinded by the conservative ideology of race hatred.

Yet Margaret remains a source of hope and integration. Following the collapse of social and economic systems, Margaret boldly espouses the values of black geniuses. She is the one who condemns the ignorance of the white supremacists that caused the breakdown of systems. At the final unravelling of the conflict, Margaret assumes the role of teacher, educator, sage, and humanist. She explodes the thesis of white superiority by extolling the accomplishments of black geniuses whose ideas and inventions made capitalist prosperity possible. Through her incantatory revelation of authentic African history and culture, Margaret educates deluded white racists to begin to yearn for the return of the extradited Black community. But it is too late as the White Community pays the ultimate price for its delusion of superiority and grandeur.

The bald summary account attempted in the foregoing sections does not truly capture the magnificent and egregious power of The Great Delusion. From a folkloric perspective, the play is a microcosm of a typical African festival; it features multiple themes, narrative and performance nuances, as well as diverse audiences. The dramaturgical aesthetics combine scenes, visual and verbal dexterity, dialogue, storytelling, songs, music, and drumming. The sights and sounds of action and speech blend almost seamlessly into a huge and intoxicating epic encounter. The epic features include the sheer number and diversity of characters. There are ten major characters and twenty supporting as well as symbolic characters such as ghosts and ancestral voices and figures. This multiplicity of images and figures underscores the festival context of the play. The structure of the stage reminds us of historical plays such as A Dance of the Forest by Wole Soyinka, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi by NgugiWa Thiong’O and Micere Mugo, as well as Dream on a Monkey Mountain by Derek Walcott. These are examples of dramatic works that explore the mythological and historical spaces that map the African experience in the context of colonial and post-colonial encounters.

The folktale narrative motif is dominant throughout the play. The opening scenes are introduced by Granny and Julian, a 12-year-old girl. Granny is described by the playwright as a “resilient woman in her late ‘50s, wise and worn by years of struggle. She carries history in her voice and hope in her eyes…” Julian is “bright, inquisitive…full of restless energy and searching questions…” Both of them serve the purpose of the narrator/audience in a folk narrative context. The generational gap between Granny and Julian illustrates the didactic function of the tale. An old generation uses the tale to transmit important historical and cultural knowledge to the younger layer of society.

In the opening scene of the play, Julian asks to know about an old white beggar on the streets. Granny explains thus:

“That is a man who believed himself king of all.

Yet built his throne on the backs of those he despised.

He mocked the hands that built his world…

until those hands walked away.

Power without justice…crumbles to ruins…”

Granny’s words recall the formulaic opening of a typical African folktale narrative that announces the theme(s), conflicts, and their resolution. This formulaic summary arouses the curiosity of the audience and stimulates them to want to hear more. This storyteller device is applied by many African dramatists such as Ola Rotimi, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Femi Osofisan, and Olu Obafemi. In this play, Ebhohon deploys this element to much dramatic and aesthetic effect.

It is noteworthy that Granny follows the white beggar’s anecdote with the retrospective poem on John Brown, the white 19th-century martyr of anti-slavery revolt in the United States of America. John Brown was executed for his rebellion. But his example fired the cause of justice and inspired other generations of anti-slavery uprisings. For example, Nat Turner, who led a black slave uprising in the 1830s, was influenced by the sacrifice of John Brown. It is remarkable that the epilogue of the play returns us to the storytelling scene; Granny and Julian are seen at the graveside of Margaret who, like John Brown, is the white heroine of the struggle for justice and racial equity.

It is hinted at the end that there is a glimmer of light for the besieged Black Community. The ones who undertook the exodus are reported to have survived the treacherous routes back to Africa. Julian prods Granny thus: “But, Granny, what happened to the Black people after they left? Did they…ever come back?”

Granny responds with a mixture of pain and optimism: “But the ones who survived? Oh, they rose… mightier than mountains, fiercer than storms. Their spark met the ember still burning in the hearts of those who had never left, and together they fanned a flame so fierce that no empire, no shadow, could quench. Together, they built cities that kissed the stars, sowed seeds of wisdom into every inch of their soil, and never again did they forget the fire buried in their bones, for with it, they lit the world anew.”

Granny explains further that in Africa the youth “launched a new awakening… Episteresurrection, they called it… Big word for a bigger dream: a mandate that every Black child would become a sacred scavenger, digging deep into the broken grounds where their ancestors’ knowledge and deeds had been buried… raising it up. Breathing life into lost songs, shattered stories, stolen sciences… and with renewed minds, they rebuilt their nations…”

Later in this scene, Granny directs our attention to an “African Aids Distribution Center – Agricultural and Business Grants” besieged by malnourished and hungry white folks. She comments that: “Those there… they return from Africa, where the Burkinabes, the Ghanaians, the Tanzanians… where the sons and daughters of the soil teach them, feed them, heal them.”

In an exclamatory tone Granny declares: “Africa leads the world now, in science, in medicine, in finance, in dreams and visions. The diamonds under their feet, the oil in their earth, the rivers in their veins, all kept by the ones once cast aside.”

This is, indeed, a mighty vision of a future utopia which Africa can attain on the basis of her natural resource endowment. But the actualization of that dream calls for a new and radical consciousness that can dare to challenge foreign exploiters and imperialists in order to reclaim the lost legacy of the continent.

As Granny warns: “Never forget, children: history bends not to the whip, but to the hand that dares to sow again after the storm.”

The Bigger Issues

The Great Delusion reignites many of the debates and discourses about the place and fate of African people in world history. The play inspires us to re-examine the crisis of memory erasure suffered by African people as a consequence of their domination and exploitation by colonial and imperialist nations over the past half a millennium. The action of the play is located within the history and experience of African people who were victims of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (1450–1850). That period of 400 years resulted in the physical removal of millions of African geniuses whose labour and ideas built the fortunes of capitalist Europe and the Americas. According to some history sources, about 12.5 million Africans were violently uprooted from their homeland and forced to work in plantations and factories of the slavers. In this regard, the losses suffered by Africa became the gain and wealth of Europe and the Americas. The African Caribbean historian, Walter Rodney, graphically describes this experience in his book, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.

However, the African Diaspora communities were not just passive victims of this horrendous experience. In their slave communities they worked and created ideas and technological innovations that transformed the economic and social fortunes of their slavers. Yet the enormous contributions of the African Diaspora geniuses are not acknowledged by the nations that benefited from them. Rather, the Africans are depicted as a people who never built anything of value and who never had a history or culture. This play challenges that racist thesis by celebrating the heroic achievements of the Diaspora communities. In this sense, The Great Delusion is a major contribution to the literature of Diaspora civilisation.

The play enjoins us to revisit the heroic epochs of African people in order to reclaim our authentic heritage. This view aligns with the position of the eminent African American historian, Professor John Henrik Clarke, when he observes: “History tells a people where they have been and what they have been, where they are and what they are. Most important, an understanding of history tells a people where they still must go and what they still must be.” (African People in World History, 1993, p. 11)

African Diaspora writers and scholars pioneered the study and propagation of African history and culture during the era of European colonization. The Diaspora intelligentsia exploited the weapon of literacy to popularize the knowledge systems of Black Africa prior to the emergence of European nations. Men and women of letters produced biographies and documentation that celebrated Africa and its various civilisations. Among ex-slave writers and historians are Phyllis Wheatly, Olaudah Equiano, Frederick Douglass, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Their creative works and autobiographies awakened the world to a new knowledge about Africa and its peoples. The Nigerian literary scholar, Professor S. E. Ogude, describes these pioneer writers as “geniuses in bondage.” Their radical and humanist thoughts influenced philosophies of democratic governance and freedom from the 18th century. Although their individual names do not feature in the play, the echoes of their influences are felt in the dialogue and scenes of action. For example, the anti-colonial movement that matured in the first half of the twentieth century was nurtured by ideas of Pan-Africanism associated with Du Bois, as well as the Negritude renaissance insurgency in the French colonies in Africa and the Caribbean. Among the Negritude voices are Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Léopold Senghor, Allionne Drop, and Cheikh Anta Diop. Cheikh Anta Diop’s works on Egyptology and ancient Africa are among the most authoritative in African history. Two of his books — African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality and Civilization or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology — are classics.

Some of the knowledge sites that radicalized the outlook of the world about Africa come from ancient Egypt and the Nile Valley civilizations. From the 1920s through the Harlem Renaissance in the United States, African thinkers and artists utilized the image of the grandeur of ancient Africa to support their campaign for racial equality. For example, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and other mass movements invoked the images of Egyptian accomplishments in their speeches and documents. In The Great Delusion, only the name of Imhotep is directly alluded to in one of the speeches by Margaret. Imhotep was the first multi-genius in human history, famous as the originator of the architecture of the pyramids, father of medicine, philosopher, and sage. African American historians like J. A. Rogers have paid tribute to Imhotep and other Black African geniuses who invented mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, writing, and literature. Rogers’s two-volume book World’s Great Men of Color is a typical example of this kind of work.

In The Great Delusion, the names of many African scientists, inventors, and innovators are recalled and celebrated. The list includes Otis Boykin (automatic control unit), Garett Morgan (traffic light), Sarah Boone (ironing board), Oscar Brown (horseshoe), Lloyd Ray (dustpan), George Carruthers (space travel/Apollo 16), Benjamin Banneker (planner of Washington D.C.), and Nigeria’s Phillip Emeagwali (computing prodigy). These geniuses of science and invention do not feature in the mainstream history of science and technology.

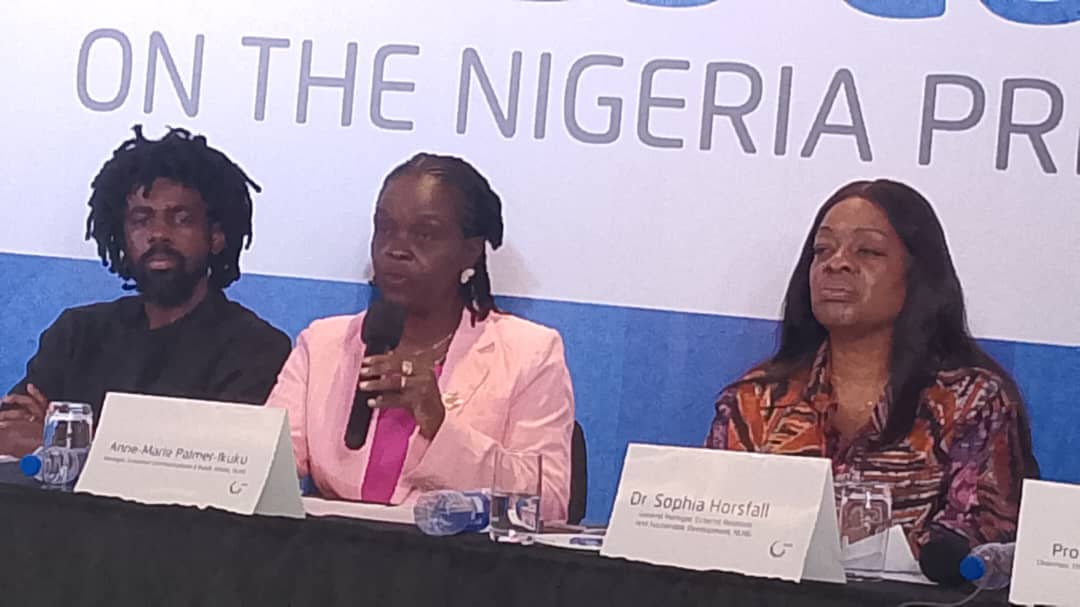

* Prof. Darah delivered this keynote address at the launch of The Great Delusion in Benin City on November 4, 2025. It won ANA Prize for Drama 2025 and will also feature at Lagos Book & Art Festival 2025 (November 10–16)6at Freedom Park, Lagos