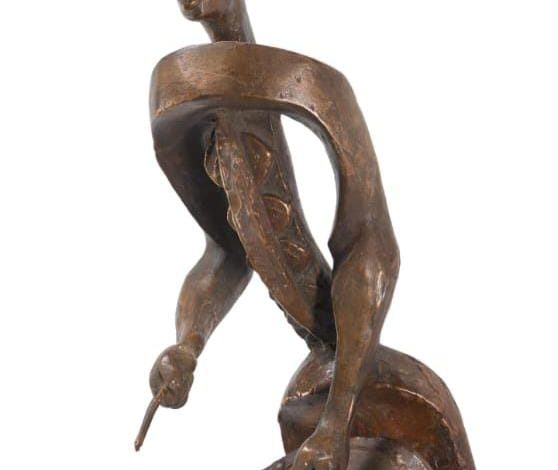

‘The Drummer’: Enwonwu’s lost landmark at NITEL House

By Mudiare Onobrakpeya

THERE are monuments a city quietly grows around objects that become part of collective memory without ever announcing themselves. In Lagos, one such monument was Ben Enwonwu’s ‘The Drummer,’ the bronze figure mounted on NET Building (later NITEL, later NECOM House) on Marina. It did more than decorate a façade; it defined an era. Commissioned in 1978 for Nigeria’s telecommunications headquarters, ‘The Drummer’ was a masterstroke of symbolism. Telecommunications is about signals; the drum is Africa’s oldest signal system—message by rhythm, meaning by sound. Steel modernity met indigenous intelligence. Nigeria at its best.

And now, by many accounts, the sculpture is gone.

Not relocated with ceremony. Not conserved in a museum. Not publicly documented. Simply absent—absorbed into the familiar silence that surrounds cultural losses in Nigeria. The seriousness of this disappearance lies not only in the artwork itself, but in what the building represented. Completed in 1979, the NET/NITEL Tower was an icon of corporate confidence on Marina. Enwonwu’s ‘The Drummer’ humanised that confidence. It was not ‘art on a wall’; it was civic language—proof that modern Nigeria could rise high without abandoning its cultural voice.

Yet the story of the sculpture’s fate is riddled with contradictions. Some public records suggest it is still there. Others—more credibly—state that it was removed. A national newspaper quotes Enwonwu’s son confirming that the work used to be at NITEL before it was taken down. Architectural commentary suggests it remained visible until around 2022, making its disappearance recent, traceable, and verifiable. This confusion is precisely how cultural assets vanish in plain sight. When certainty dissolves, accountability follows.

NITEL’s institutional collapse and the murky afterlife of its properties created ideal conditions for heritage loss. But one principle must be stated clearly: the sale or transfer of a building does not automatically include the right to remove public art. Privatization is not permission to privatize memory.

So what happened? There are only three plausible scenarios. First, removal for renovation or safety—if so, there should be records, condition reports, storage locations, and photographs. Second, quiet transfer into private hands—where silence slowly converts patrimony into (private) property. Third, outright theft disguised by bureaucratic confusion. Any of these scenarios is traceable—if the will to investigate exists.

Public sculpture is not like private painting. A painting can disappear into a home. A public monument disappears in full view—and the public is told to move on. When a society accepts that, it signals that stealing from the commons is easy.

What is required now is simple but firm: A public declaration of the sculpture’s status. A proper inventory of Enwonwu’s monumental works. Heritage and law-enforcement involvement. And a recovery effort focused not on scandal, but on restoration and public access.

In the end, ‘The Drummer’ is not just a missing bronze. What is missing with it is governance—the discipline of knowing what we own, where it is, who is responsible, and how it is protected.

So, the question must remain alive, and unanswered rumors must give way to documents: Where is Ben Enwonwu’s ‘The Drummer’? Until that question is answered clearly, every institution connected to that building remains part of the chain of disappearance.

* Onobrakpeya, born in Lagos, is searching for the Enwonwu iconic statue