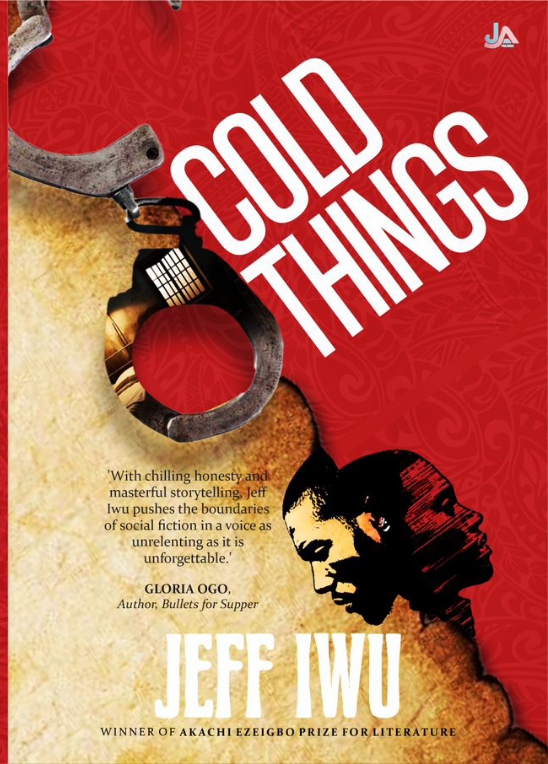

Iwu’s ‘Cold Things’: A haunting testimony of familial trauma, survival, redemption in postcolonial Nigeria

By Ifeanyi John Nwokeabia

IN his novel Cold Things, Jeff Iwu carves a brutally honest narrative of intergenerational trauma, toxic masculinity, systemic abandonment, and the psychological wreckage of familial betrayal. The novel is set against the chilling backdrop of Manjo City and its claustrophobic prison walls. Iwu’s prose is lyrical and visceral; he blends Igbo idioms, Nigerian street wisdom, and searing realism in a story that resonates like a wound. Iwu depicts not just the scars of the body but the cold imprints left on memory, silence, and love.

Cold Things centres on Ekene and Obioma, two cousins whose lives intersect through trauma, secrets, and eventual imprisonment. Ekene, an emotionally shattered youth, lives under the shadow of a violent father, Patrick, and a mother, Ijeoma (known as Momsy), caught in a web of patriarchal suppression and survival. Obioma, the son of Mrs Felicia, Patrick’s estranged sister, escapes to the city in search of safety, only to fall into the hands of Uncle Lambert, a predatory bachelor whose “hospitality” is a cover for sexual exploitation. These parallel plots converge within the broken walls of Manjo Prison, where injustice, corruption, and the weight of repressed truth ferments.

Iwu does not merely narrate suffering, he equally anatomises it. To achieve this, he explores Ijeoma’s haunted resilience to Ekene’s descent into emotional implosion, and Obioma’s explosive act of vengeance. In short, every arc is a meditation on survival in a nation where justice is either commodified or deferred indefinitely. As its title suggests, Cold Things is saturated with a certain affective temperature; chilling, numbing, unrelenting. Coldness in the novel is symbolic to loss, betrayal, loneliness, and guilt. When Ekene laments, “I learnt to live in darkness. I learnt to live in death,” the prison becomes a metaphor for Nigeria itself, a state of psychological entrapment where hope is rationed and justice is postponed.

Madness is both metaphor and reality. Ekene’s unravelling tales within the prison is at once the product of systemic neglect and the internalisation of grief, loss, and unspoken guilt. Similarly, the prison itself becomes a psychological space where time folds and memory becomes spectral. Family, too, is rendered not as a sanctuary but as a battlefield. Iwu’s portrayal of maternal stoicism (especially in Ijeoma) is reminiscent of Buchi Emecheta’s exposition of womanhood in The Joys of Motherhood. Yet, unlike Emecheta, Iwu’s Cold Things presents mothers as not just sacrificial, but as subversive. They know the system and either endure it or flee from it, like Ijeoma the narrator in the epilogue who leaves Manjo City to start anew in a nameless village.

In a similar vein, the character of Uncle Lambert is one of the vilest, yet compelling figures in the novel. He is initially described with warmth; “white diastematic teeth flashing like lights,” but gradually he is emerges as a symbol of familial predation, echoing the culturally tabooed but often silenced reality of incest, sexual abuse, grooming within extended families. Obioma’s experience is delivered in haunting precision. The trauma is neither overdramatised nor understated. Iwu captures the slow corrosion of innocence, his narrative voice carefully exposing how betrayal by those we trust most can catalyse both psychological breakdown and cathartic violence. That Obioma eventually kills Lambert, as the narrator recounts in a quiet, redemptive tone; “they say he fought like a man possessed by demons,” feels not like a climax but an inevitability.

The prison system in Cold Things is not just a setting; it is a character. The Manjo Prison is a rotting symbol of Nigerian state failure. Inmates are packed beyond capacity, medical aid is minimal, and warders act like “area boys in uniform”. They are easily bribed and complicit in systemic rot. The raid led by Chief Officer Olabosun Tukunbo and Assistant Officer Haruna Bala, triggered by leaked photos of inmates on Facebook, uncovers phones, condoms, spirits and shame. As Popsy’s idiom goes; “where all dogs eat faeces, only the one with shit-stained lips gets flogged.”

The portrayal of Jazy, the enigmatic, cancer-stricken gang leader whose eventual death is as mysterious as it is metaphorical, underlines the novel’s nihilistic interrogation of masculinity, sexuality, and mortality. Doctor Johnson, Gimba, Bode and other inmates are not just filler characters. They are fragments of Nigeria’s moral and legal breakdown. Each has a story, a pain, and a reason for being cold. One was betrayed by his wife; another killed in a moment of rage. These men represent the collateral damage of systemic injustice.

Iwu’s prose style is both lyrical and colloquial, reflective of a Nigerian orature tradition enriched with idioms, proverbs, and urban slang. Phrases like, “grease their palms” or “that’s the spirit, keep it hot” give the narrative an authentic rhythm, reminiscent of Chinua Achebe’s balance between English and Igbo worldviews. But beyond language, Iwu’s voice is unafraid of silence. There are quiet moments in the novel like Ekene sitting in a dark cell, Obioma staring at Jazy, Momsy weeping in front of Popsy’s ghost. These moments are all drenched in emotional stillness. They are powerful not for what is said, but for what is unsaid.

In one of the novel’s most chilling passages, Ijeoma says: “The bruises Patrick left on my skin. The curses his mother spat at my back. The sneers of Mrs Felicia. The shadows they planted in my heart.” These expressions are poetry, drenched in lament and yet resilient. By the end of the novel, Ekene and Obioma meet again. This reunion is not redemptive in the traditional sense; it’s tentative, eerie, and even spectral. They hold hands and disappear into the smoky ruins of a prison breakout, unsure of where to go next. This is not a story of heroes. This is a story of survivors: of boys who were once warm but grew cold; of men who were once innocent but became beasts of burden and of women who carried whole families on the soft skin of their backs until they bled.

The epilogue, narrated by Ijeoma (Momsy), is a powerful close. It returns us to voice, to a woman who escaped, survived, and now tills the earth with her bare hands. It is in this final reflection that Cold Things achieves catharsis: “Here, in this forgotten place, I till the soil with my hands. I plant yams, cassava, bitterleaf… There are no cold things here, only warm hands, kind greetings, children with dust on their feet and light in their eyes.” This passage echoes the final lines of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, a return to breath, earth, and self after so much death.

Cold Things is not just a novel. It is a reckoning. It reckons with our silences, our domestic violence, our prisons; both literal and emotional. Iwu, with this novel, joins the ranks of established socially conscious writers in crafting literature that bruises the conscience and reminds us that fiction can still be revolutionary. It is though, rooted in the local: Red Light Street, Manjo City, Akah Villa, its reach is global. Trauma, injustice, family, and survival are universal themes. However, what sets this novel apart is its bold refusal to sentimentalise pain. Iwu offers pain raw and unrelenting, and then lets the reader decide what redemption might look like. In the end, all that remains are cold things, the novel insists.

* Nwokeabia is a teacher, an essayist and a reviewer