Fela: A requiem in 15 iterations

By Dami Ajayi

FELA passed away twenty-eight years ago yesterday. I felt somewhat numb about that detail. I surprised myself. I did not write a commemorative piece, not for the lack of trying. Instead, I reviewed everything I have written about Fela in the last decade. The short essays. The digressive op-eds. The book reviews, the most recent one is his late first wife’s memoir, Mrs Kuti. I dredged up some old tweets, looking for something I have not already said about my first music hero.

* My parents say I loved Fela since I was an infant. My father dubbed the vocables on his beast of an anticolonial tune, ‘Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense’ into a side-long cassette play which was on replay constantly because if stopped, I became inconsolable.

* My defiant teenage years featured very little Fela. American music was king. On the radio, his radio-friendly tunes were for background listening on Sundays for those daddies who don’t attend church with their families. His seemingly endless instrumentation required the patience that a teenager programmed to the American radio three-minute track format could not muster.

* My friend began to experiment with grass after secondary school. With that proclivity also came his love for Fela’s music. I would sit with him while he moulded his spliff, listening to Fela’s tunes like they were an adjunct sacrament to his deep drags. He deified Fela. Soon enough, he was deep into colourful conspiracy theories about Fela’s death involving the CIA and the Nigerian government. A lethal injection and a live HIV virus were involved. I listened to my guy lose his mind in instalments to Fela’s discography.

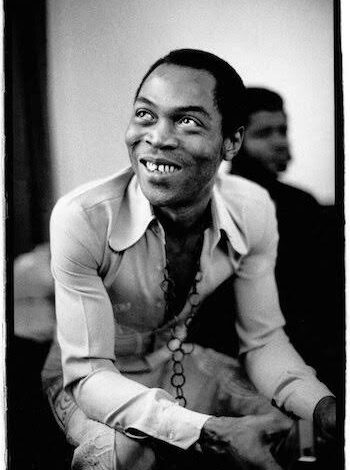

* In my final year at medical school, I saw the 1980s documentary film, Music Is The Weapon. Fela was in his mid-40s, contesting to be Nigeria’s president. He spoke eloquently with unusual charm and charisma. His face was expressive and animated. His eyes warm with liquid fire. His sax solos are equal parts smooth and fiery. Then I fell in love again with his music once again, particularly with the song ‘Power Show’, which illustrated something faulty about human nature.

Fela

* We edited early issues of Saraba to Fela’s Trouble Sleep (Palaver). When I lived in Ilesa, ‘Coffin for Head of State’ was my tune. In Anambra, I fell in love with his early stuff, the LA 69 Sessions and the highlife records. In Yaba, Tunji force-fed us ‘Beasts of No Nation’. In London, I fell for the early stuff, those ambitious highlife tunes sitting at the interface of bebop jazz and highlife. Fela was always ambitious, and he worked hard. He understood legacy, too. He christened Ambrose Campbell the father of modern Nigerian music, but it was JO ‘Skippy’ Araba he wrote a song for. ‘Araba’s Delight’.

* As a young, educated Nigerian man, the myth of Fela and the martyrdom of the Kuti family was irresistible. Fela’s creative arc was the stuff of genius. It felt like what happens when hard work meets innovation. His genre, Afrobeat, was perfection. A vehicle that carried both a groove and gunpowder. His messaging was earthy, delivered in the lingua franca of the Nigerian working class. His humour was wicked, deployed instructively. His contradictions are messy. But his mischief was the main ingredient for manufacturing his myth.

* His presence looms large in the Nigerian consciousness as a countercultural Christ, who eschewed his class privileges to live among the proletariat and precariat, broke bread with them and spoke for them. When he died from an HIV-related illness, his myth kicked into motion. His music became the gospel he left. His words are a sacrament.

* Some insist that Fela was a prophet. He seemed more like an astute chronicler of his times. What has happened is that the Nigerian state has not evolved beyond the power dynamics that he noted. We have yet to rid ourselves of the strong men who usurped powers enshrined in institutions for their personal use.

* Fela was a powerful man, too. The books that have outlived Kalakuta Republic suggest that he was some kind of dictator. Not his only foible; his misogyny was just as brazen. His first wife’s memoir does little to hide his failings as a husband and father. He always seemed like an irreparably extroverted man whose vanity was his outsized ego and persona. He desperately wanted to be loved by his peers and cronies. Fela’s delight was to play saviour, to champion a cause for the people, but this came at a cost that drew not just from him; his loved ones paid dearly too.

* Some swear by the music. Those who can peel back the layers of myth would say that the Egypt ’80 era is less than the Afrika ’70 era. I am inclined to agree that the gunpowder consumed the groove at some point. The message later outweighed the music. I am wary of music that insists on a teachable moment, particularly at the expense of musical mastery. Fela’s social commentary was at its best at the instance of lampoonery.

* Some swear by the Berlin 78 Jazz Festival. Fela in a yellow jumpsuit, prancing on stage. It is not even his second-best concert. One cannot say that Afrika 70 went out with a bang!

* There is the matter of the sleek drummer Tony Allen and his legitimacy as a co-creator of Afrobeat. Did Fela write his drum work? Did Allen innovate and improvise his parts? On one far end of the spectrum are those who believe that Allen put the beat in Afrobeat. On the other end, some insist Fela brought Afrobeat down Moses-style from Mount Sinai (or Mount Rushmore).

* The older I become, the less persuaded I am by myth. The more I find that my favourite version of Fela is the artist as a young man, full of mischief and ambition, happy to cram all of his innovation into a form that could hardly garner the attention of the public, but would provide him with the delight of creating.

* Siri, please play Fela’s ‘Ai Ga Na’!