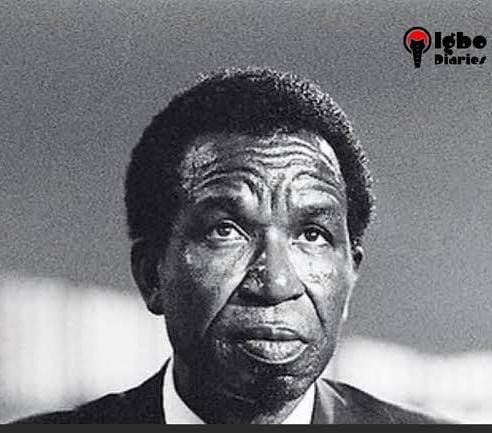

Cyprian Ekwensi: My encounter even till death did us part

By Uduma Kalu

CHINUA Achebe. Cyprian Ekwensi. Two greats whose two of my exclusive stories at The Guardian rocked the world. And this was before I encountered Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche and again, with The Guardian, helped to shoot her to national and international consciousness. It was deliberate. It was intentional, focused and successful.

But Ekwensi first. There will be time for many tales. My encounter with Cyprian (COD) Ekwensi is indelible. That was before I would make global headlines with the return of Chinua Achebe to Nigeria after nine years of self imposed exile and medical attention in the United States in 1999, the year democracy returned to the country. I was like his media person in those years of Ekwensi’s isolation in Surulere, Lagos.

I was at The Guardian then, in charge of its Literature page, perhaps the most intellectual page of that Africa’s most authoritative newspaper. We were resurrecting The Guardian Literary Series after years of comatose beginning first with the weekend titles. And as the Literary Editor, I was assigned the task of many things, including interviews. It wasn’t an easy thing tracking this one of the earliest makers of Nigerian and African novels, aptly dubbed the Father of West African Novel.

Ekwensi began writing novels long before the generation of Achebe stepped in after their learning the craft in the departments of English and humanities and founding literary clubs such as Mbari Club in Ibadan where literature was debated and treated as serious business. Some of the members of this group would later become the definers of the path that today is known as modern African literature and arts.

But long before this were Ekwensi, and well, Amos Tutuila, reputed by African writers such as Ben Okri as the Founder of Magical Realism. While Ekwensi was engaged in the lives of ordinary folks in the emerging West African cities starting with his first novel, People of the City, Tutuola engaged in the mythical and fairy tale tradition of magic.

Between the two was the issue of craft. Yes, Ekwensi’s craft as Tutuola’s is often described as linear but Ekwensi, apart from being more realistic, dealt with contemporary realities and concerns, while Tutuola’s was more straight plot, which is typical of traditional folktales. Characterization was another problem as well as their engagement with issues as literary artists.

It’s no surprise that both Ekwensi and Tutuola would suffer acerbic criticisms from fellow African writers and critics who described them as a shame to African fiction. About the same time were also the pioneer poets – including Nnamdi Azikiwe and Dennis Osadebay whose poems were described as not literarily sophisticated, being more of advocasies than poetry.

Well, it took Achebe, who later became known as the Father of African Literature to reimage Tutuola’s work as a serious work with then reigning poet, TS Eliot, giving it a stamp of authority.

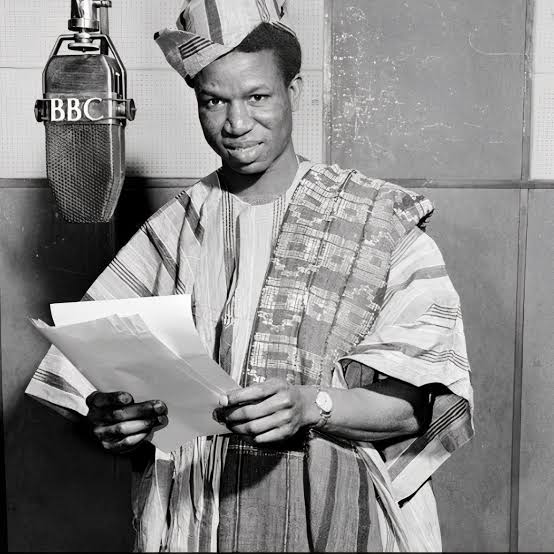

Younger Cyprian Ekwensi at the BBC

That began the serious engagement of Tutuola as an important writer so much that he is now considered the pioneer of magical realism, long before Nobel Prize Winner in Literature, Gracia Marquez wrote his defining novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude. It took a white man, an American, Prof. Charles Larson, to change the narrative against Ekwensi. Still, these two pioneers are often riled against and ignored in African literary studies, even though they are studied as African literary canons.

All this filled my mind as I went about the crowded streets of Yaba and Ojuelegba looking for Ekwensi. I had been briefed on how to get to his house, number 129 or so Ojuelegba road, Surulere. I had to trek from Yaba bus stop, dodging both human and vehicular traffics, asking at the many houses numbered even and odd numbers in a confused manner. But finally, I saw the house, white, a storey building.

In front of it were shops selling plastics and other things. One of the attendants, a lady, directed me to the back of the building, upstairs. I went through the back with clustered concrete and untidy. It was neat. I was curious,

I had visited Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka’s bush house in Ake, Abeokuta. An estate lost in the jungle. Well, he is said to have built it from proceeds of his Nobel prize money. WS was said not to have a dime to build a house then. So, immediately the Nobel cash prize came, Soyinka was hurried by his friends to build the house. John Pepper Clark lived in high brow estate at Ikeja. TM Akuko lived in another grand house in an Apapa estate. Mabel Segun’s Ibadan house was a marvel. That was before I met Elechi Amadi in his dreary Aluu, Rivers State house. I was told Achebe has a small bungalow in Ogidi, his Anambra State hometown. But I was a a frequent visitor in his University of Nigeria Nsukka house as a student. It was beautiful bungalow in the elite professors’ quarters of the University, full of gardens and flowers.

I mean, when compared with the aforementioned contemporaries or so of his, and for Ekwensi to live in such dreariness shocked me. But Nigeria had gone to such ugliness. How can a writer of such high selling titles be in such situation? I wondered.

But I continued, climbed up the iron staircases with the iron rails. Two doors stayed at me. The one directly before me and the one on my left. It was a tiny space between the stairs and the doors. I knocked on the left door as directed by the shop owner.

There was a movement inside, and shortly after, the door opened. A very tall and black man appeared. Maybe in a singlet or white shirt. Whichever, he was casual in a wrapper and a white top. He was cool. Not surprised to see me. There was a current between us. That current is always there whenever I encounter fellow kindred spirits. It will be as if we know each other and have been on the literary project for ages. Indeed, the literary project is a relay only those truly called are eternally forged and sworn to in that immortal task that goes on and on and on forever.

We exchanged greetings. It was late afternoon. It had taken me hours to get to Yaba and track him to Ojuelegba. The Lagos traffic was hell. One could get trapped for over five hours.

Then, he unlocked the small iron gate blocking the door.

It’s a typical Nigerian security guide to secure themselves thrice in their homes. An iron gate in front of the house. The iron door of the house isn’t usually enough. An iron gate is also usually added. This is discounting sn estate that has its own gates. Surulere, especially, the Ojuelegba axis, was a notorious place. A popular red light district was located there. Fela, the eminent aftroeat musician sang of the area, its frenzy traffic and chaos.

Ojuelegba was also a place of relief for travellers caught in the night. They would stay at the place to await morning if the ubiquitous buses that plied there weren’t going their routes in those dreads of the nights. Ojuelegba was a typical Lagos metropolis, always alive all day and night.

That was where Ekwensi’s first important novel, People of the City, was written, Ekwensi began. I had muttered the disorder of Ojuelegba and the difficulty I faced tracking him. I had expected him to live in Lagos Island as an elite, not in the noisy and boisterous bus stop of Ojuelegba with a nasty history – prostitution, robbery, thuggery, noise, riots, drugs, low life.

But Ekwensi told me he sold his land in Lagos Island to build the house in Ojuelegba. He hated the silence of the elites. Ojuelegba then was emerging. The island had filled up and people were pushing out to the mainland. Ojuelegba was a forest.

As we spoke, he told me how Lagos kept expanding. As Surulere got chocked up with no more lands and accommodation, Lagosians moved to a virgin area, bought the lands cheap and started developing it. That was how Mushin, Oshodi, Ikeja, Ipaja, Ikorodu, and other areas of Lagos exploded.

I then told him of the house the Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka built in the bush. That bush had played an important role in Soyinka’s life. He had escaped, posing as a hunter. Soyinka says he is a hunter. Whether he has ever killed a game or not is another story. But that night, early in the morning, when General Sani Abacha’s killer squad came calling on him, the forest came to his aide.

Ekwensi smiled. I never saw him laugh out loud all through the years I met him. He said Soyinka hadn’t actually seen forests. That was when he told me he was a surveyor. He was among those that catrgraphed the country back then. And he traversed the deep forests of Northern Nigeria. One of the deep forests depicted in novels such as The Passport of Mallam Illia and An African Nights’ Entertainment is Kumirukuku, one of the jungles of the North in today’s Zamfara State.

He said he loved Ojuelegba. The noise and vibes of the area fired his creativity. Silent places like Lagos Island wouldn’t have inspired him. Then Ekwensi brought out a box filled with black and white photos. Those photos were images of partying city men and women and showed that Ekwensi wrote while looking at those photos as remainders.

I asked him. He agreed. Those stories were real stories rendered as fiction. If decoded, much of Ekwensi’s works are autobiographies then.

He smiled as he admired those pictures. I understood. Remembrances of things past.They were mostly women. And Ekwensi’s female characters, city women, were mainly of loose types, such that Christian or rural women would say had gone haywire, and were without redemption.

He remembered the endless parties. Ekwensi was in those endless parties in the novels and his experiences as one of Nigeria’s emergent elites in the nation’s capital, Lagos, rising out of rural life to a global recognition, became for us a slice of the life of the many emergent African cities then.

Well, his later colleagues would join him in this depiction of the city and contemporary life of a new nation long after they were done retelling the late 19th century pre-Nigeria and Africa. It’s no doubt that Ekwensi showed the path to the African city novel.

That encounter marked the beginning of my close relationship with Ekwensi.

Before he died in 2007, I knew he was trying to tell me something. I wanted to hear his sensual and sexual escapades as told in his novels like People of the City and Jagua Nana. But none of us could say it. But the black and white photos were eloquent. The stories were real.

Before he died, I helped to bring Achebe and Ekwensi together. That was 1999, when Achebe returned to the country. I had broken the news of his return for The Guardian. My boss, Mr. Jahman Anikulapo, had asked me to get reactions from literary greats on the return.

I told him of Ekwensi. Mr. Anikulapo jumped at it. Achebe’s son, Ike, had told me where they were staying that night – Sheraton Hotel, Ikeja. I was invited for an interview. And The Guardian, which broke the news, was highly interested in escalating the scoop through an exclusive interview, both as news and as weekend literary pages. It was a feast. Then, there was a coup and a scoop..

Then, phones were difficult. No mobile phones.

I left for Ekwensi’s house the next morning. And told him of Achebe’s return. Ekwensi was surprised. He didn’t give me the interview. Rather, he asked me to take him to the hotel. I had left afterwards as we later agreed that he would join us. He did join us. I can hardly describe the emotion I saw between these two giants.

Because from the moment Ekwensi knocked on the door of Achebe’s suite and burst into the room, the conversation changed. It was like an elder visiting another elder after a long exile. Like Obierika and Okonkwo when Okonkwo returned to his hometown after his seven years’ exile.

I recall now, immediately Ekwensi burst into the room, Achebe, stuck in his wheelchair, half raised himself and lifted his right hand and embraced Ekwensi and called him ‘Cyorain’. It was affectionate and deep. Ekwensi smiled and calked him, Chinua. I could understand. Larson was in Massachusetts and Achebe was there too. Achebe must have played a role in Larson’s interest in Ekwensi; after all, Achebe established the African Writers Series that published Ekwensi’s serious novels.

Then the story began. And The Guardian was there to scoop the whole story, a story of two giants in deep and personal conversation about the nation they envisioned in their youth and fought for as adults in many ways, even as Biafrans. Sadly, both have passed on, with nightmares of the country haunting them till death. Indeed, there was a country!

Though there was something said between the two; that left unsaid was ominous. I recall the day Ekwensi died. 2007. I will tell this story later. But credit must be given to the poet, Chike Ofili.